Marvel is battling copyright termination notices over some of its most famous and valuable characters. Here’s what it all means.

As you’ve probably heard by now, Disney-owned Marvel Characters, Inc. fired off a slew of copyright lawsuits this past Friday seeking to invalidate termination notices served over such blockbuster comic characters as Spider-Man, Iron Man, Black Widow and several other Avengers mainstays. As with any good story (especially a story about comic book characters), the narrative has been decidedly over the top:

Don’t get me wrong – these are fascinating cases that should yield some interesting legal opinions down the line. That said, I’ve been seeing quite a few uninformed takes on the internet about the termination notices, the lawsuits and their potential effect. Here’s my friendly neighborhood attempt to set the record straight:

Is Marvel Really Going to Lose Its Rights in Spider-Man, Iron Man and Other Characters?

In a word, no. But first, let me explain what’s going on. Last year, the heirs of some of Marvel’s most well-known Silver Age comic writers and artists served copyright termination notices under section 304(c) of the Copyright Act. That’s the law that gives artists and their heirs an opportunity to recapture previously transferred copyrights after 56 years. As it did with a similar termination notice served over ten years ago by the heirs of Jack Kirby, Marvel went on the offensive, filing five separate lawsuits seeking declarations that the termination notices are invalid. The complaints were filed virtually simultaneously in three different federal jurisdictions—an attack reminiscent of the Avengers’ coordinated assault on Thanos in “Endgame.”

Here are links to each of the complaints, filed against Larry Lieber and the estates of Steve Ditko, Don Heck, Gene Colan and Don Rico. The lawsuits ask the respective courts to declare that the artists’ and writers’ contributions to such characters as Spider-Man, Iron Man, Black Widow, Falcon and others were created as “works made for hire”—which, as I’ve discussed in other posts, aren’t eligible for copyright termination.

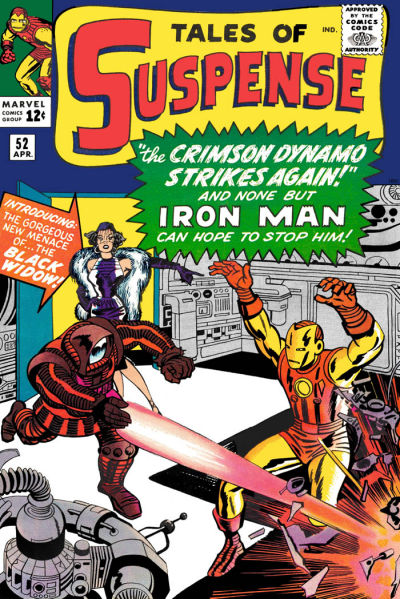

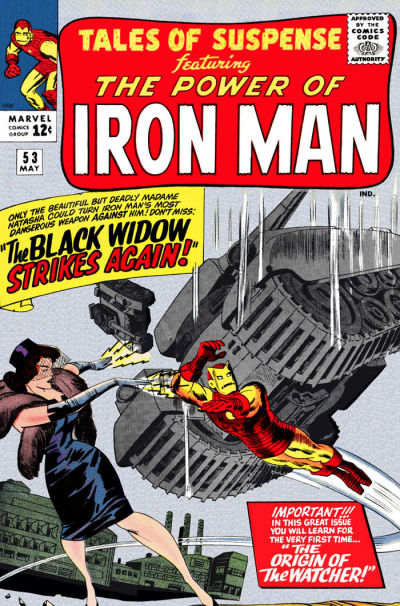

I’ll get to the work for hire issue in a minute, but the fact is that Marvel won’t “lose” its rights in any of these characters even if the termination notices are ultimately deemed valid. That’s because none of the affected writers and artists created any of these characters by themselves. Instead, they’re all “joint works,” to which several individuals contributed. For example, Black Widow, which first appeared in 1964’s “Tales of Suspense #52” was created jointly by Stan Lee, Don Rico and Don Heck. Unlike Rico and Heck, who were freelancers paid on a page rate, Stan Lee was a fully employed editor on salary. Therefore, even if the estates of Rico and Heck were to successfully terminate rights in their contributions, Marvel would still jointly hold rights to the Black Widow character based on Lee’s contributions, which were clearly made on a work for hire basis.

Why does this matter? Well, when comic book stories, dialogue and artwork are merged together, they become a part of a single joint work as a matter of copyright law. Typically, any co-owner of a joint work has the ability to exploit the work without the permission of its fellow owners, subject to a duty to account for a share of the profits. Therefore, even if Marvel were to lose these new lawsuits, it won’t “lose” any rights to utilize its characters. At most, it would have to share some of its profits.

Tales of Suspense #52 Tales of Suspense #53

Are These Works Made For Hire?

Not only won’t Marvel lose rights in its characters, it probably won’t lose its lawsuits either. Under existing law in the Ninth and Second Circuits (within which all five complaints were filed), the writers’ and artists’ contributions will almost certainly be deemed works made for hire that aren’t eligible for termination. That’s because these circuits both employ the “instance and expense test” with respect to copyrighted works created prior to 1978. Under the instance and expense test, a traditional employer/employee relationship isn’t required for the hired party’s contributions to be considered a work made for hire. Instead, it’s enough that the hiring party is the motivating factor in inducing the creation of the work and has the right to direct and supervise the manner in which the work is carried out.

In applying this test, courts have taken a pretty liberal view of the degree to which a hiring party must be involved in the creation of a work, whether at the inducement or preparation stage. It’s not necessary for the hiring party to be the precipitating force behind the work, and the right to control or supervise the creator’s work doesn’t actually need to be exercised in order to result in a work made for hire.

The Kirby case, which was decided by the Second Circuit back in 2013, provides a clear roadmap for the courts who will eventually decide the new lawsuits. The court in Kirby described the “Marvel Method” utilized by Stan Lee, in which Lee would provide an outline or synopsis to his artists, who would then draw the comics based on Lee’s guidelines. Thereafter, writers would add captions and dialogue to the artwork. As editor, Lee retained the right to edit, change or reject anything the artists or writers contributed.

If anything, it may be easier for courts to find that the works created by Lieber, Ditko, Heck, Colan and Rico were works made for hire. That’s because, by most accounts, Jack Kirby was given more editorial freedom by Stan Lee compared to Marvel’s other contributors. Back in 1968, Lee recounted that while Kirby was credited as an artist, he plotted many of the stories himself: “Some artists, such as Jack Kirby, need no plot at all. I mean, I’ll just say to Jack, ‘Let’s make the next villain be Dr. Doom’… or I may not even say that. He may tell me. And then he goes home and does it.”

In the Kirby case, the court acknowledged Jack Kirby was given more freedom to work under the Marvel Method than other artists and made many creative contributions to the works on his own. They included creating and drawing new characters and “influencing plotting, or pitching fresh ideas.” Nevertheless, these original contributions and Kirby’s status as a freelancer weren’t enough to give him ownership over the characters he helped create. The same is likely to be true with respect to the contributions of the set of writers and artists that are the subject of the new lawsuits.

There is one wild card—but it’s a longshot. While both the district court and Second Circuit ruled in favor of Marvel in the Kirby case, the lawsuit settled just as the U.S. Supreme Court was in the process of deciding whether to take the case. While the “instance and expense” test rules are well articulated within the Second and Ninth Circuits, the Supreme Court would ultimately have the final say, assuming any of these cases makes it that far.

What Else Should I Know About the Marvel Cases?

There are a few other nuances worth mentioning briefly, because they will certainly blunt the effective impact of the copyright termination notices even if they are ultimately upheld.

First is the fact that termination only affects U.S. copyrights. No matter what the outcome with respect to these cases, Marvel’s ability to fully exploit its foreign rights (and retain all of the profits from that exploitation) will remain intact.

Second is the issue of apportionment. Even if Marvel were required to share profits with the original creators, the split wouldn’t be down the middle. That’s because the creative properties at issue have been developed over many years with the addition of ancillary stories, characters and character attributes contributed by people other than the characters’ original writers and artists. Marvel could use these newer contributions without accounting to the terminating parties’ estates, although the financial calculations would be incredibly messy to figure out.

Finally, even if the termination notices were effective, the artists’ heirs would be extremely limited in what they could do with any recaptured rights. At best, they would only be able to exploit the version of the particular characters’ attributes and artwork contained in the works subject to termination. Any character traits, plots or other material first introduced in later works would be off limits.

Taken together, these copyright termination wrinkles mean that, as a practical matter, the artists’ and writers’ heirs would almost certainly end up reaching a deal with Marvel to re-assign the copyrights at issue even if they prevail.

Got any more questions about the new Marvel copyright termination lawsuits? Let me know in the comments below or @copyrightlately on your favorite social media account.

2 comments

Hey, Aaron – once again, your analysis is cogent and spot on! Thanks for creating this publication! Best, David

Hi David – I really appreciate you taking the time to read and comment! Thanks so much!