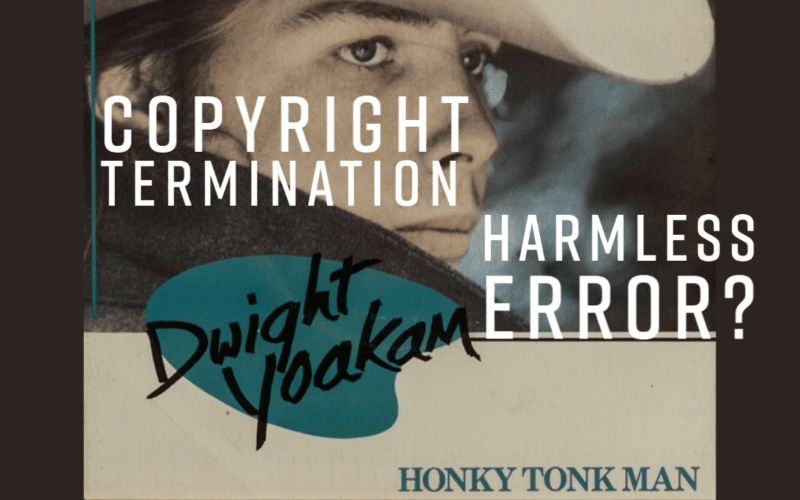

As a new case involving Dwight Yoakam illustrates, serving a copyright termination notice is fraught with potential pitfalls, and mistakes come easy and often. Can the “harmless error” doctrine save the day?

For a copyright lawyer, there are few things as nerve-racking as preparing a copyright termination notice. (Although having to constantly explain that there’s no such thing as a “five second rule” is right up there.) It’s not so much that termination notices are difficult to prepare—although they can be. It’s more that the consequences of making a mistake can be severe. In the worst-case scenario, an error in the notice may prevent an author from ever recapturing rights in a copyrighted work.

The Copyright Act’s statutory termination provisions, when used correctly, give authors (and in certain cases, their heirs) the right to terminate prior copyright grants, effectively giving them a second chance to renegotiate a better deal. But the termination statutes are highly technical. Different rules apply depending upon whether the original grant was entered before or after January 1, 1978. And in either case, the termination window only remains open for a short period of time—five years—and at least two years’ advance notice must be given before the notice is effective. Waiting until the last possible moment to serve the notice may increase a terminating party’s leverage in negotiating a new deal, but may also leave too little time to serve a new notice in the event there’s a mistake.

The Harmless Error Provision

Recognizing the high stakes at issue, regulations adopted by the Register of Copyrights do include a safety valve of sorts, known as the “harmless error provision.“ The harmless error doctrine generally states that errors in a termination notice that don’t materially affect the adequacy of the information required to “serve the purposes” of the termination statutes won’t render a termination notice invalid.

But as a new district court decision reminds us, trying to determine whether any particular error is in fact “harmless” can be a fact-intensive inquiry that may require a trial to sort out—at which point it may be too late to fix.

Yoakam v. Warner Music Group

The plaintiff in the new case is country music superstar Dwight Yoakam, who’s recorded five Billboard No. 1 albums, along with twelve gold and nine platinum albums. (You may also remember Yoakam from his great role in the Billy Bob Thornton film “Slingblade.”)

Many of Yoakam’s hits were released pursuant to a recording agreement between Yoakam and Warner Music first entered in November 1985.

The Copyright Termination Notice

In a letter dated February 5, 2019, Yoakam’s lawyer transmitted two notices of termination to Warner—one for Yoakam’s sound recordings and the other for his music videos. Each of these termination notices was prepared pursuant to Copyright Act section 203(a), which covers grants executed on and after January 1, 1978. Under the statute, termination “may be effected at any time during a period of five years . . . . begin[ning] at the end of thirty-five years from the date of publication of the work under the grant or at the end of forty years from the date of execution of the grant, whichever term ends earlier.”

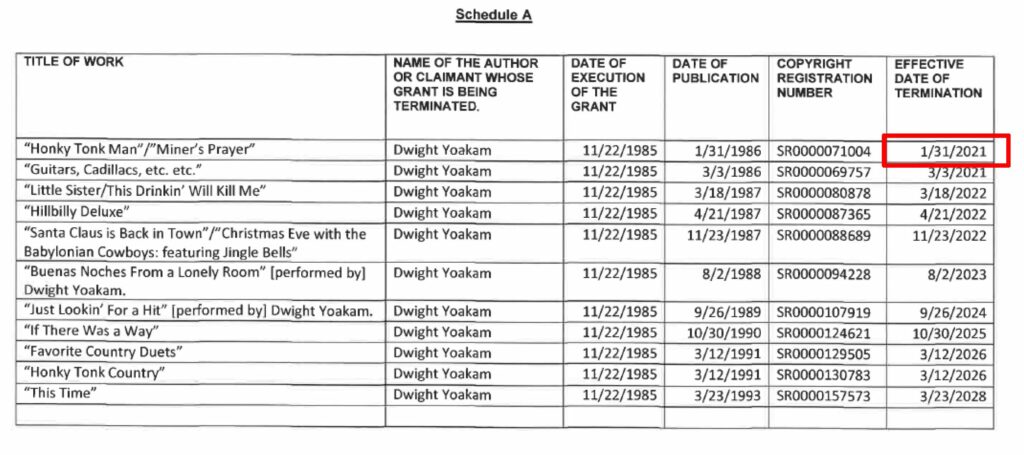

For all of the works listed in Yoakam’s termination notices, the notices gave effective termination dates exactly thirty-five years from the date of publication, which is the first date on which termination could be effected under section 203(a)(3). Here’s a copy of a key page from the termination notice:

As the chart shows, each of the effective dates is precisely thirty-five years from the date of the work’s first publication. However, for two of the works, the singles “Honky Tonk Man” and “Miner’s Prayer,” the use of the earliest eligible termination date was a problem. That’s because Yoakam’s notice wasn’t actually served until February 5, 2019, while the effective date listed in the notice was January 31, 2021.

The Mistake

Apparently Yoakam’s lawyer had originally planned on serving the termination notice on January 31, 2019. Instead, the notice was served five days later, but the effective date of termination for the singles wasn’t updated. Therefore, on its face, the notice was served five days short of the two-year minimum notice period required under section 203(a)(4)(A).

Based on this error, Warner Music filed a motion to dismiss Yoakam’s complaint for copyright infringement. The record company argued that because Yoakam’s notice was served on less than minimum notice, it wasn’t effective in terminating Warner’s rights in the songs.

Yoakam, on the other hand, took the position that the mistake was the result of an “inconsequential and harmless scrivener’s error.” He alleged that the intended effective termination date was actually February 5, 2021, not January 31, which would be exactly two years from the date of service and well within the five-year termination window.

So What is a Harmless Error?

The harmless error regulation (37 C.F.R. § 201.10(e)) is limited to “harmless errors in a notice.” Examples provided in the regulation include errors in the date of execution of the grant being terminated, the date of copyright registration, and the registration number of the work, “if the errors were made in good faith and without any intention to deceive, mislead, or conceal relevant information.”

In considering the viability of Warner’s motion to dismiss, Central District of California Judge Stephen Wilson described the court’s task as distinguishing between errors in the termination notice itself (which might be excused if harmless) and errors arising out of Yoakam’s failure to comply with the statutory timing requirements (which can’t be excused).

The problem is that this is not a particularly clear distinction. For example, should listing an erroneous date that provides less than two years notice (e.g., February 5 instead of January 31) be treated as a typographical error, similar to listing “February 5, 3021”? Or does the erroneous date constitute a classic timing error, resulting in the notice having been served too late to be effective?

An Unbendable Rule with an Inescapable Effect?

There’s not a ton of case law on the point, and what authority does exist is fairly inconsistent. In Johansen v. Sony Music Entertainment, a court in the Southern District of New York faced a situation similar to the one in Yoakam, as the effective date of termination listed for one of the songs at issue in that case was only 23 months after the notice was served. While Sony argued that this was an “error in timing” that couldn’t be excused, the court found that it was at least plausible that the mistake was a “scrivener’s error” that could be saved by the harmless error rule—at least for purposes of getting past a motion to dismiss.

Conversely, in Siegel v. Warner Bros. Entertainment, part of the long-running “Superman” copyright termination saga, the court suggested (in construing a similar termination statute, section 304(c)), that “[o]nce a termination effective date is chosen and listed in the notice, the five-year time window is an unbendable rule with an inescapable effect, not subject to harmless error analysis.”

That sort of bright-line analysis was also echoed by the Acting Register of Copyrights, who noted in addressing the “harmless error” doctrine in 2011 that “if the wrong date is recited in the notice and a court subsequently determines that the actual date of execution was at a time that places the effective date of termination or the date of service of the notice of termination outside of the statutory windows, the harmless error doctrine will be of no assistance.”

The Court’s Ruling in Yoakam

In the Yoakam case, the plaintiff in essence asked the court to treat his termination notice as it if had listed February 5, 2021 as the effective date, as opposed to January 31, 2021—thereby giving Warner a full two years’ notice to prior to termination. Because Yoakam was not seeking to recapture his rights any earlier than the statutory minimum time frame, he argued that the error in the notice should be excused.

In ruling on the motion to dismiss, Judge Wilson found that it was at least plausible that Yoakam’s termination notice erroneously communicated the intended effective date. Therefore, the court allowed Yoakam’s infringement claim to proceed past the pleading stage.

Importantly, however, the court simply found that Yoakam’s harmless allegation might qualify as harmless error, not that it necessarily does. While it may be plausible that Yoakam’s counsel simply failed to update the effective date in the termination notice, the facts also tend to suggest that the effective termination date communicated by the notice was in fact correct—but that Yoakam’s error was in serving the notice five days later than his counsel originally intended.

What’s Next?

Ultimately, the issue of whether Yoakam’s mistake qualifies as a excusable “harmless error” or not will end up being a “case-specific inquiry” that can only be determined following discovery, perhaps on summary judgment, but possibly only after a full trial.

So while Yoakam’s case won’t be dismissed, he still runs the risk that after several years of litigation, the judge or a trier of fact could eventually find that the error in his termination notice wasn’t harmless. This puts Yoakam in the unenviable position of having to decide whether to either take his chances with the existing notice or else serve a new termination notice, thereby potentially giving the record company at least another two years to exploit his songs before the copyrights are recaptured.

The Bottom Line

Regardless of the ultimate outcome, the Yoakam case should serve as a cautionary tale underscoring the importance of triple-checking a termination notice before serving it, just to ensure that everything’s correct. While the termination statutes may have been designed in order to give authors and their heirs a second chance to profit from their works, Congress certainly didn’t make it easy.

As always, let me know what you think, either in the comments below or on the Copyright Lately social media accounts @copyrightlately. In the meantime, a copy of the court’s decision in Yoakam is below.

View Fullscreen

4 comments

As always, thanks for the background and analysis!

Really interesting and helpful stuff, Aaron. As a bit of a termination nerd, I love all of your termination coverage here.

Hello can you help me with downloading the court document. Apparently your website does not allow downloading the court judgement pdf directly.

Sure! Just click on the link “View Fullscreen” link above the post, and then there’s a download icon in the upper right hand corner.