Guest Post by Meshandren Naidoo and Dr. Christian E. Mammen

A world first – South Africa recently made headlines by granting a patent for ‘a food container based on fractal geometry’ to a non-human inventor, namely an artificial intelligence (AI) machine called DABUS.

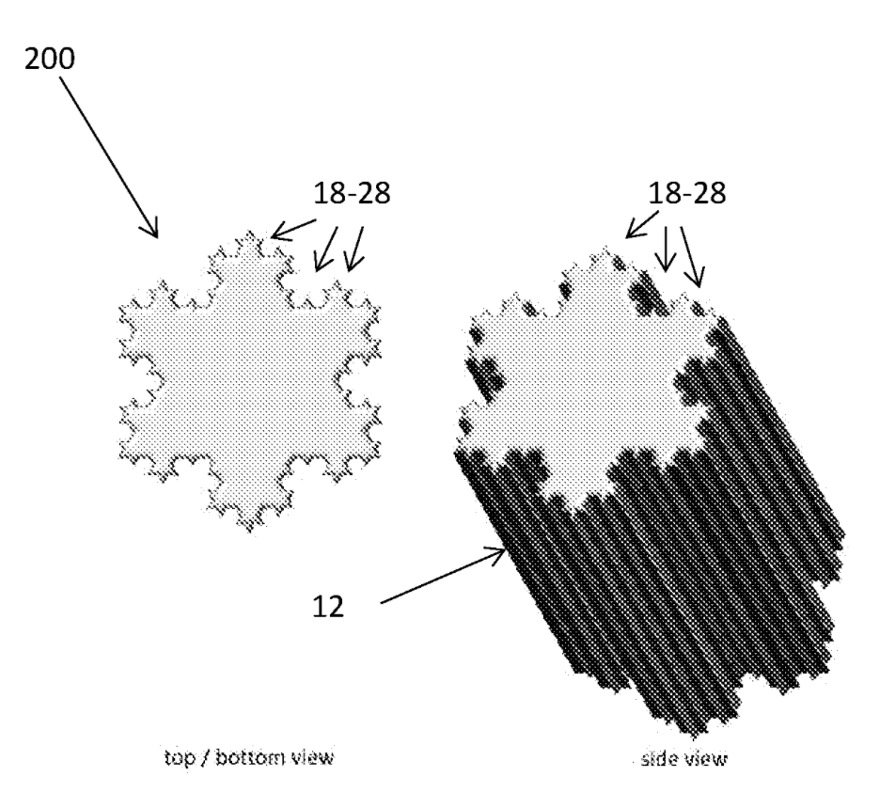

Over the past three years, the AI algorithm DABUS (short for Device for the Autonomous Bootstrapping of Unified Sentience) and its team of supporting humans, including Dr. Stephen Thaler and Prof. Ryan Abbott, have made headlines around the world as they sought patent protection for a fractal-inspired beverage container (shown below) that they contend was invented by DABUS.

Notably, their application has been denied by the United States Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO), the United Kingdom Intellectual Property Office (UKIPO), and the European Patent Office (EPO). The grounds for rejection have included a mix of procedural formalities, formal legal requirements, and theoretical objections. The procedural formalities and formal legal requirements, which have been equally important to the theoretical questions in these decisions, are sometimes overlooked in the popular media. They include such issues as whether (and how) Dr. Thaler obtained authorization from DABUS to file the patent application, and whether the patent statutes include a requirement that inventors be human. Each of these three jurisdictions found sufficient reasons in these formalities to reject DABUS’ patent applications. In addition, the EPO focused on the broader question of legal personhood: namely, that a number of other rights and obligations are attendant upon being an inventor, and unlike humans, an AI lacks the legal personhood to discharge those obligations and exercise those rights. The UK courts reasoned similarly, noting that an AI lacks the capacity to hold property, and therefore could not have authorized Dr. Thaler to act on its behalf. The USPTO emphasized that under US law invention requires “conception” followed by reduction to practice, and reasoned that “conception” requires a theory of mind that is simply not established to be present in an AI.

Critics of those decisions have emphasized the role of patenting as a part of national industrial policy, and in particular the role of patent grants in encouraging innovation. With increasingly capable AI algorithms, the argument provides, the ability to innovate is shifting from an exclusively human domain to one that includes the algorithms, and modern industrial policy needs to encourage and reward that shift.

These same factors appear to have come into play in the South African decision, though to a clearly different outcome.

The pitfalls of formal examination in South Africa

In July 2021, South Africa’s patent office, the Companies and Intellectual Property Commission (CIPC), granted the South African DABUS patent application, which was published in the South African Patent Journal. Unlike the USPTO, UKIPO and EPO, the CIPC does not conduct a more thorough interrogation of patent applications, known as substantive search and examination (SSE). Instead, all that is required in a formal examination (also known as a registration-based system) is for the application forms and fees to be in order with the specification documents attached. If these affairs are in order, the patent will summarily be granted by the CIPC. This, along with the lack of information provided by the CIPC post-grant has led to criticism directed towards its non-examining nature. This limited review for compliance with the procedural formalities appears to have reached a different outcome than the USPTO, UKIPO and EPO, finding that Dr. Thaler is empowered to apply on behalf of DABUS. No further information has thus far been given by the CIPC relating to the grant. It should be noted however that the ongoing patent reform in South Africa provides for training and infrastructure upgrades to accommodate a shift towards implementing SSE.

Does substantive South African patent law preclude AI inventorship?

The South African Patent Act 57 of 1978 (Patent Act) does not define an ‘inventor’ hence it is arguable that the Patent Act could, or should, be interpreted to include AI. However, the Patent Act presents some challenges in doing so such as, inter alia, the requirement for the provision of names and addresses of inventors—the EPO cited a similar requirement in denying DABUS’ application. If the reasoning of the USPTO is followed, a further challenge to the DABUS patent in South Africa would be the ‘first and true inventor test’. Like the ‘conception’ test in American patent law – the object of the test is to determine the identity of the ‘devisor’ of the invention. With that said, it is open for the South African legal system to determine if the test, which was originally crystallised in South African law in 1902[1] (with not much development taking place between then and now) is a bar to AI inventorship. Whilst case law[2] which explains the test also refer to pronouns such as ‘he’ or ‘she’, South Africa could diverge from the USPTO and employ a more purposive approach to its interpretation (which is the Constitutionally recognised manner of interpretation) as opposed to a more textual one.[3] This statutory interpretation method would include broader considerations in the process such as (1) advantages posed by AI inventorship; (2) policy directives; (3) the fact that AI inventorship was unlikely to have been considered during the period when the test was originally developed and; (4) the object of the test is to determine the identity of the deviser of the invention in the event of disputes and the like – not to preclude other non-human entities from innovating.

Was granting the patent a mistake?

At first glance, it may appear that the DABUS patent was erroneously granted by the CIPC. Although there has been a shift towards digitization, the CIPC has struggled extensively in the past with infrastructure and administrative issues. But it may be premature to conclude that the granting was erroneous. The post-apartheid government foresaw the challenges associated with the exclusion of a large portion of citizens from economic participation, and central to the solution was science, technology, and innovation. This culminated in the White Paper on Science and Technology in 1996. Soon after, came many other strategic policies aimed at placing South Africa and its citizens in a stronger position. In 2019, the Presidential Commission on the Fourth Industrial Revolution and an updated White Paper on Science and technology was published – both of which highlighted the need for a technology-orientated approach to solving socio-economic issues.

Unfortunately, innovation (noted in the 2019 White Paper on Science, Technology, and Innovation) as measured in products produced and patent output from South African applicants in the country and in other jurisdictions via the Patent Cooperation Treaty (PCT) has remained ‘relatively flat’. Adding to this was policymakers’ concerns of ‘the brain drain’ – the emigration of skilled persons in search of better opportunities and environments.

In April 2021, a call for public comments on the proposed National Data and Cloud Policy in terms of the Electronic Communications Act 36 of 2005 highlighted three main points: (1) the South African Government aims to create an AI institute to assist with reformation; (2) the intention of this is to encourage investment in, and exploration of, AI as a means to achieve sustainable development goals and economic growth; and (3) AI is viewed as a solution to some of the capacity issues facing South Africa.

Thus, as a matter of national industrial policy, it is entirely possible that the grant of DABUS’ patent is fully consistent with the emphases on broad access, digital innovation, and support of science and technology generally.

An opportunity for South Africa?

Given that South Africa is currently undergoing major patent reform, South Africa’s policymakers may find that it would be prudent to capitalise on any presented advantages. Support for, and recognition of, AI inventorship could make South Africa an attractive option for investment and innovation and may also cause these systems to be viewed as a sustainable form of innovation. The path forward for South Africa is uncertain, but there are opportunities in recognising AI as an inventor that could aid in achieving the national policy goals. In doing so, South Africa may champion the Fourth Industrial Revolution and signal leadership to other countries. Indeed, in just the few days since the South African DABUS patent was granted, the Australian Federal Court appears to have followed suit, overturning a rejection of DABUS’ application by that country’s patent office and finding that recognizing AI inventorship would be “consistent with promoting innovation.”[4]

[1] Hay v African Gold Recovery Co 1902 TS 232 p 233.

[2] University of Southampton’s Applications [2006] RPC 567 (CA) paras 22–25.

[3] Bertie Van Zyl (Pty) Ltd v Minister for Safety and Security 2010 (2) SA 181 (CC) para 21.

[4] Josh Taylor, “I’m sorry Dave I’m afraid I invented that: Australian court finds AI systems can be recognised under patent law,” The Guardian (July 30, 2021) (https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2021/jul/30/im-sorry-dave-im-afraid-i-invented-that-australian-court-finds-ai-systems-can-be-recognised-under-patent-law)

Mr Meshandren Naidoo is a Ph.D Fellow at the University of KwaZulu-Natal (South Africa) and member of the African Health and Research Flagship. His areas of interest are AI technology, intellectual property, business strategy, and bioethics. His Ph.D involves looking at the challenges posed by AI technology to South African patent law and what the potential solutions may be.

Dr. Christian E. Mammen is an IP litigation partner with Womble Bond Dickinson in Palo Alto, CA. He has practiced in San Francisco and Silicon Valley for over 20 years, and has held visiting faculty positions at a number of universities, including Oxford University, UC Berkeley Law School, and UC Hastings College of the Law. He has written and spoken extensively on AI and patent law, including “AI and IP: Are Creativity and Inventorship Inherently Human Activities,” 14 FIU L. Rev. 275 (2020).

The authors confirmed they did not receive compensation for this article and that they do not represent any clients that might be impacted by the article or the underlying decisions. The views expressed by them in this article are solely their own.

So what? South Africa is a registration country. I could register my dog license as a patent in ZA if I wanted to, because there’s no substantive examination by the patent office. Nothing interesting happens until enforcement time.

While I agree that the South African instance is less interesting (based on a formalities process), and certainly the Australian case is just opening the door to the patent process, the attitude of “nothing to see here” is woefully off.

Follow the link at 7.

One of several over at the other blog:

link to ipwatchdog.com

Will the U.S. PTO issue new inventor declaration and power of attorney and assignment forms to be [artificially?] signed by the AI inventor when equivalents of these applications are filed in the U.S.?

Y

A

W

N

Let’s not confuse OTHER actions with the actions (and direct legal point) of inventorship.

We have plenty of time to address those once the prime issue is resolved.

(FAR too many want to use such questions as a mere mechanism to thrust their head into the sand and not deal with that prime issue at all)

The obvious answer to that (fairly small) problem is simply to amend the statute to remove the requirement for an inventor declaration.

Greg, not as easy a fix as you suggest. I have lived long enough to see the political repercussions of prior corporate attempts to remove the requirement for inventor signatures and inventor declarations [or any other attempt to leave valid inventorship designations entirely up to corporate employers].

BTW, as to this liquorish-stick shaped container and its conception, does not some real person had to have the prior conception to program the AI software for some desired end result, such as internal volume, surface area or structural strength, etc.?

Presumably developments in AI will provide the impetus to get past those political qualms. I agree that the politics of the necessary changes might be difficult (lots of gasbag rhetoric about “small inventors” or “ordinary Americans,” “tinkering in their garages,” and other such folderol), but the actual legislation is easy enough (just start with Title 17 and adjust as necessary to account for differences between patents and copyrights).

Nevertheless, once AI emerges on the scene, we will either adjust the patent laws to account for that change, or else we will essentially cease to have a patent system. A lot of products will not be commercially feasible to bring to market without a patent system, so politicians will either have to swallow back their gasbag rhetoric or else witness the emergence of long term tech stagnation.

Nevertheless, once

AIsoftware emerges on the scene, we will either adjust the patent laws to account for that change, or else we will essentially cease to have a patent system.There, fixed it for ya.

What do you have against a mere design choice of wares in the computing arts?

After all — per your own mantra — each of the wares are nothing more than machine components.

Or do you not understand what software is?

I would put it that Greg’s Big Pharma perspective colors his choice of paths forward (and descriptions of those paths) in an entirely myopic (and thus dystopian) Big Corp way.

The problem is if I own a machine that invents something did I invent it? I would be the first human that has conceived of the invention, but I did not invent it in the conventional sense of inventing.

Still, one could limit it to a human conceiving of the invention and then the first human to read and understand the invention would be the inventor. So that has a problem as then it is some weird race to see who is the first human to understand the invention.

So saying that the machine was the inventor is probably right with ownership being separate.

This is going to have some profound repercussions on the “unpredictable” arts when a simulation can make them predictable arts.

The way to think about this is that there is some structure that is the invention and the machine came up with it. I think what is a bit odd is whether there is a qualitative difference between say me writing a program to figure out the best configuration for say a ladder where I put in so many constraints that one could say I invented it. This is in contrast to say a machine where few constraints are put in and it invents the ladder.

Maybe it goes to conception. Where it depends how the AI was programmed. Can you say you conceived of the invention based on the programming or not? If yes, then you are the inventor. If no, the machine is the inventor.

Again, I note that now machines are the inventor and the CAFC would still hold all these machines as ineligible under 101. It is mind boggling.

“whether there is a qualitative difference between”

Easy answer (if you know this tech): Not only is there a qualitive difference, there are a quantitative AND LEGAL differences.

AI is simply not the same as merely programming to achieve a set answer.

(and yes, quite besides the question of inventor, you are correct in how the product would be labeled ‘abstract’ and thus not eligible for patenting — our pal Marty even sees this)

“I would be the first human that has conceived of the invention,”

NOT a true statement.

Reading the work of another is NOT conception.

I have detailed this out previously in the manner of having a black box and two rooms.

In the first room, an actual invention is made and that invention is detailed and put into a black box.

The black box is then transported to a second room, and we can vary the details here for lots of implications, but for a first instance, let’s go with: the “owner” sits at a table, and opens the black box and merely reads what is in the box.

In no sane world is that owner the actual one that did the conception.

This is easily seen by merely having the first room (and conception) be done by a human. That second person in the second room has done nothing different and it is simply illogical to ascribe to him the honor of inventor depending on circumstances that can so vary, with his actions being exactly the same.

For a twist, we can have that person in the second room NOT be the owner. What then to your example, Night Writer?

For another twist, we can have – instead of a person in that second room, an automated internet blast feed, such that countless people — at exactly the same time — all are reading the contents of the black box.

This is going to have some profound repercussions on the “unpredictable” arts when a simulation can make them predictable arts.

+1

.. and p00r Greg won’t realize (or admit) just who raised that as an issue first…

>The problem is if I own a machine that invents something did I invent it?

Yes, just like if you would be if you created an algorithm to optimize a design using Monte Carlo techniques.

IMHO, the use of the term “artificial intelligence” to describe neural network models is pure marketing.

My practice includes this area and I can guarantee you that this is not merely marketing.

O.C. , even if the term “artificial intelligence” may describe programing and then feeding lots of data in neural network models or the like software systems, a novel and unobvious such system should logically be patentable without patent law changes. But what is in debate here is whether or not an output thereof is the invention of the system itself or its programmers. Or, as you suggest, no invention at all if someone takes an existing such system and uses it conventionally? But what if the output is completely unexpected and unpredictable?

“IMHO, the use of the term “artificial intelligence” to describe neural network models is pure marketing.”

Outside of patent applications, I agree entirely.

Within patent applications, I think the use of the term is an attempt to get more claim scope than is deserved.

NW, AI has lots of issues, including my tongue in cheek questions at 6 above, but I do not think “race to see who is the first human to understand the invention.” is one of them. Because really understanding an invention scientifically is not a 112 requirement [versus the result and one or more ways of how to make and use it]. E.g., when that famous 18th century inventor accidentally dropped a bit of soft rubber with some sulfur mixed in it onto a hot stove he had no idea about the vulcanizing process going on in that bit of rubber, then or when he filed his patent application, he just noticed that it had hardened the rubber.

Paul, the issues of “race to see who is the first human to understand the invention” is not one of a deep understanding of its workings but something akin to conception.

Not understanding vulcanizing but rather how to perform vulcanization.

The more I think about it, the more I think it is either the AI is the inventor or there is no inventor.

The more I think about it, the more I think it is either the AI is the inventor or there is no inventor.

Exactly correct. The U.S. patent system faced an analogous question back in the pre-Civil War era, whenever a slave invented something. Slaves were not legal “persons” either, and could not apply for patents in their own names. Because their owners were not, however, the true inventors, neither could the owners apply for patents. The result was simply that such inventions were not patentable, and thus they were protected by trade secret for the most part.

That is the equilibrium toward which we are heading if we do not revise Title 35 to permit patents on inventions with AI inventors.

+1

… another aspect of the conversation that yours truly first introduced…

If an AI can be the inventor, then:

If an AI controls an autonomous vehicle and causes an accident that kills a natural person, can the AI be charged with negligent homicide? If found guilty, what is the penalty? (An AI is already constructively in prison.)

If an AI can be the inventor, then:

Can an Extraterrestrial be the inventor?

If an AI can be the inventor, then:

Can my cat be the inventor? My cat is very smart. She has already invented a method for arranging the blanket on the bed in my guest room to make a warm shelter for herself.

Can an Extraterrestrial be the inventor?… Can my cat be the inventor?

The limited authority we have on these questions suggests that the answer is “no.” Naruto v. Slater, 888 F.3d 418, 425 (9th Cir. 2018). Congress can change that answer, however, whenever it so chooses.

As the seized court in Australia wisely observed, you have to distinguish between inventorship and ownership. Ownership is the issue that it is proper to dispute.

Let the applicant for patent nominate who or what it pleases, as inventor, I say. It’s not important. Just let the patent statute declare that the right to the patent is deemed to vest in the legal person who made the application, subject only to challenge by another legal person in possession of a better right to the patent.

You know, like the 1973 European Patent Convention decreed back in 1973. Problem (if ever there was one) solved, I say.

While I often agree with you, Max, I cannot do so here.

When you expand the scope of who, or what, can qualify as an ‘inventor’, you expand the range, and pace, at which patents can be granted. This is a matter that profoundly affects economic policy. Should a country like Australia (or South Africa) that is a net importer of technology and IP create more opportunities for foreign entities – particularly the big tech companies that dominate AI – to obtain monopoly rights enforceable against the public at large?

There are no international treaty obligations requiring any country to recognise inventions made by non-humans. For once, this is a situation in which sovereign states are actually free to implement their own national policy. If a country wants to say ‘no, we are not going to open our doors to this’, then it is free to do so.

I am on record as being opposed to the Australian Federal Court decision. I fully expect that it will be overturned on appeal or, if not, overruled by legislation, because it does not serve Australia’s national interest, and it is not consistent with current government policy focus on balancing IP rights against the broader public interest.

Saying that the inventor is ‘not important’ fails to recognise that patent rights do not exist in a vacuum. They are an instrument of economic policy grounded in practical reality.

If I manage to breed a goose that lays golden eggs, I hardly need somebody to come along and artificially increase the value of golden eggs to incentivise my efforts. Ryan Abbott is wrong. We do not need an additional patent incentive to encourage the development of creative machines.

Mark,

While I certainly understand the Sovereign-centric underpinning of your views (and have emphasized such myself many times), the overall thrust of your position is coming across as xenophobic and downright anti-patent.

Further, on another blog you provided more details, but those details simply do not support your reductionist mindset, and actually supports the opposite in that the Australian version of “Quid Pro Quo” dictates no change in level of grant to foreign entities — to which your position much more strongly aligns.

This NIMBY attitude actually contradicts popular wisdom (as seen in the past history of the US vis a vis Pharma and software in that a more rather than less “Pro-patent” position invites development of that tech within the Sovereign.

Mark,

Upon a re-read, there is an aspect of your statement that follows that is not correct (this is not an AI as inventor angle). And it’s not even a trans-Sovereign thing at that (so technically, you are not incorrect in that regard)

“There are no international treaty obligations requiring any country to recognise inventions made by non-humans. For once, this is a situation in which sovereign states are actually free to implement their own national policy. If a country wants to say ‘no, we are not going to open our doors to this’, then it is free to do so.”

Where there IS an intra-Sovereign requirement in most all Sovereigns requiring recognition of invention (that happens to have been invented by AI) is in the recognition of the State of the Art.

Do you know of ANY Sovereign that will decide that invention by AI can be disregarded under patent law when evaluating a new (non-AI) invention against the State of the Art?

The comment above about ‘becoming predictable arts’ does not even scratch the surface.

I would be Curious ( ) just how many people grasp that.

) just how many people grasp that.

Well well, Mark. I wasn’t expecting that argument. Thanks for setting it out. I agree with you, that too many patents is as bad for technological progress as too few, but I’m sceptical of your “national interest” point. I think every country should strive to confine patent grants to contributions to technology that are characterized by a step forward that is inventive. I think that the scope of claims should be crimped back to be strictly commensurate with the size of the contribution and must be enabled over that full scope. Otherwise, the claim ought not to be allowed and if allowed swiftly revoked on request.

Anon will get on my back yet again but insofar as these are the fundamentals of the EPO’s posture, I commend the EPO for its stance. On the Governing Body of the EPO (the AC) sit government representatives from 38 sovereign States. The AC sits with impunity above the Rule of Law and treats EPO employees disgracefully, as non-human objects, but in its setting of the priorities of what subject matter should be granted in the 38 countries and what should be refused, I have no quarrel with it. For me, it is a matter of indifference to national interests whether the act of invention is ascribed to an AI or a human intelligence.

If we allow an Applicant to ascribe inventorship to an AI, will that lead to abuses? I don’t know but I have a feeling that time will soon tell us.

“Anon will get on my back yet again but insofar as these are the fundamentals of the EPO’s posture”

THREE strikes here MaxDrei.

1) Mark is correct as to national soveriegnty

2) there is no such thing as “too many patents” and

3) In no way is the notion of too many patents the fundamental of ANY patent agency.

Whatever caveats you then want to state for a PROPER patent, such simply does not affect the plain fact that a patent is a good thing, and more patents can only be a good thing.

As to “abuses,” I am still waiting for someone (Mark included) to detail just how an abuse may arise. All I see there are reflections of the factory workers getting ready to throw their sabots into the machines (along the lines of the urban myth: link to alphadictionary.com ).

I hear you, Mark, and agree with your main point. Net importer of technology jurisdictions should not create more opportunities for foreign entities to obtain monopoly rights enforceable against the public at large in those jurisdictions.

Really, in hindsight, TRIPS was a mistake. There is no reason why (e.g.) AU or BR or ZA should have to promulgate IP laws appropriate for CN/EP/US in order to participate in the global free-trade regime. Ideally, we should just rescind TRIPS and let individual jurisdictions make these decisions on the basis each of its own self-interest.

At that point, it would make sense for CN/EP/US to grant patents on inventions with non-human inventors. I agree, however, that it is less clear why AU (or AR, or ZA, etc.) should do so.

I should say that when I talk about rescinding TRIPS, I really mean with regard to patents & copyrights. With regard to trademark law, a measure of international harmonization really is necessary for the global trade system to function. It will not do for a boatload of “Louis Vuitton” handbags to arrive in (e.g.) Sydney with no assurances as to whether LV really did (or did not really) manufacture those handbags.

I think that Mark provided a study that considered:

Net importer of technology jurisdictions should not create more opportunities for foreign entities”

But ended up NEITHER making any substantive changes nor imposing ANY ‘count’ limit on foreign participation in the Australian Sovereign’s patent system.

Is that accurate, Mark?

Hi Greg,

Assuming that by ‘mistake’ you mean ‘instrument foisted upon the rest of the world by a small number of countries that are net exporters of IP as a condition of membership of the WTO’ then yes, TRIPS was a mistake.

In its report following review of Australia’s IP arrangements in 2016, the Australian government’s Productivity Commission concluded that:

International commitments substantially constrain Australia’s IP policy flexibility.

− The Australian Government should focus its international IP engagement on reducing transaction costs for parties using IP rights in multiple jurisdictions and encouraging more balanced policy arrangements for patents and copyright.

− An overdue review of TRIPS by the WTO would be a helpful first step.

The report also noted that ‘processes for including IP provisions in trade agreements, in particular, have suffered from a lack of transparency and a weak evidence base.’

It’s hard to argue with that!

Mark,

You have not answered some simple questions put to you – vis a vis that 2016 report that you have now referenced several times.

I am Curious, did Australia decide to make any substantive patent law changes in view of that report?

Did Australia KEEP the same substantive law in place?

Did Australia invoke ANY type of limits on these dreaded foreign interests seeking to partake WITHIN the Australian patent system that (I am supposing) offers a particular Quid Pro Quo such that ANY rights grants are granted in view of the BENEFITS accrued from the participation in Australia’s patent system?

Your complaint is coming across as xenophobic, and frankly ungrounded – but more importantly, the apparent LACK of changes following that 2016 report seem to paint the opposite takeaway that YOU are trying o imply from that report.

I grant that you may be fully correct in your feelings. But I have seen nothing that would vindicate those feelings.

As to the item being hard to argue, it is difficult to even begin formulating a discussion without understanding more of the actual particulars. What item(s) lacked transparency? What item(s) needed or even were suggested to be nice to have ‘evidence,’ and what types of evidence were sought, or if not sought, could be sought?

I mean, if your only intent is to climb atop a soapbox and rant – mission accomplished. But if your intent was to actually substantiate your feelings, well, you need quite a bit more to achieve that.

Assuming that by ‘mistake’ you mean ‘instrument foisted upon the rest of the world by a small number of countries…

Touché. Really though, my point is that it was a mistake for those small number of countries to think that it was in their own self-interest to get (e.g.) Fiji or Peru to treat IP the same way that we treat IP.

Supposedly this was a favor that those small number of countries were doing for their pharma and entertainment industries. Really, though, how much tangible benefit did any of those industries realize on account of the TRIPS changes? To a first approximation, the answer appears to be “none.”

The whole thing (at least with regards to patents & copyrights) appears to be deadweight loss. You would be hard pressed to identify “winners” from TRIPS (except perhaps for folks like yourself—viz., IP attorneys in small market jurisdictions).

Re: “Let the applicant for patent nominate who or what it pleases, as inventor, I say. It’s not important.”

Max, that may be the attitude in some places like Australia,* but it is a political non-starter in the U.S., as noted at 6.2.1

*I once uncovered an Australian patent agent having named, without inventor or corporate consent, or any cooperative activity, an employee of client company A on an Australian patent application by company B as a joint inventor. I objected, and was told that was acceptable there.

Paul, do you remember the old days, when the UK patent statute included the concept of the “communication invention”. There, the inventor was named as the entity to whom the invention was “communicated” from outside the jurisdiction.

The underlying idea was that the progress of useful arts, within the jurisdiction, would be promoted by granting patents, within the jurisdiction, to those who brought the invention in, from outside the jurisdiction, thereby enriching the state of knowledge of technology, inside the jurisdiction.

We could resurrect the idea, giving a patent to those who receive a communication from an AI.

We could resurrect the idea, giving a patent to those who receive a communication from an AI.

Good point. This seems more awkward than simply listing the corporate employer as “inventor,” but it is better than the status quo.. I would not want to make the perfect to be the enemy of the good.

Re: Do I remember “granting patents, within the jurisdiction, to those who brought the invention in, from outside the jurisdiction.”

Max, I’m not THAT old. UK grants of “patents of importation” for non-novel inventions ended a long time ago, and was never in U.S. patent law.

[What we have now in the U.S. as a sort of substitute is competition between cities and states for who can give the biggest and longest tax breaks for somebody allegedly bringing in new business.]

Sorry for my infelicitous language, Paul. I’m not that old either, but I do remember being taught about the notion of a communication invention and a patent of importation when I was studying to pass the written examination to qualify as a UK patent attorney.

On tax breaks for those bringing in new business, a good example is Tesla in the German federal state of Brandenburg. For the German economy, electric car factories are very important. Amusingly though, Mr Musk likes to talk about his factory in cutting edge Berlin, but that of course is another state entirely.

See the twist above at

link to patentlyo.com

To Greg’s point, if Congress wants to revise Title 35, that’s up to them I guess. Likewise, if S. Africa sees fit to allow this kind of patent and inventorship, that’s of course their prerogative. Although, as the article notes, the examination, such as it is, in SA doesn’t seem all that rigorous.

That much aside, as I see it, the problem is not really the “attribution” question of “who (or what) is the inventor?” Rather, it’s an issue of patent term evergreening. One can potentially get not just an initial patent on the AI itself, but also a new patent every time the AI produces a later output—even after the initial patent has expired. In that case, it would seem to effectively make the term of the initial patent never-ending or nearly limitless. That feels like a far bigger concern to me than duking it out over who or what gets inventorship bragging rights. But I’ll concede that the issues are interrelated to an extent.

Huh? If I patent the AI, and then the AI invents a new rubber composition, the patent on the rubber composition does not—at all—prevent anyone else from using my AI at the end of the patent term.

You have a point. Maybe “evergreening” isn’t really the right term to be using. I’m not sure this is an issue that’s come up before, although others might have encountered it. You are correct of course that anyone else could use the AI itself once the initial patent expired. But there still seems to be a problem of “double dipping”—for lack of a better expression—if you can keep getting a further patent on each subsequent output. I’d argue that the AI itself entails the full universe of all its possible outputs. So after the term of the initial patent has run, that’s it, you don’t get anything more based on outputs the AI generates later. It doesn’t seem like we’re anywhere near the point of this becoming an issue yet, but eventually I suspect it will.

And since you mentioned copyright too, I’m trying to think of a comparable scenario in that field. The monkey selfie case doesn’t interest me, because that’s an attribution issue separate from the timing problem I’m focused (no selfie pun) on. Consider Jackson Pollock. His paintings were all of course different, but in some sense they were also variations produced by the same underlying randomized process. And he could get a separate copyright on each painting at the time he made it. But what about an actual machine that likewise made Pollock-esque paintings? Does it work the same way, again, not with respect to attribution, but for copyright term? Given that copyright term is so long anyway, I’m not sure it’s worth considering, but it’s still sort of fun to think about.

Kotodama,

The situation that you seem to want to paint actually tends more to a potential outcome of NOT recognizing AI as an inventor.

The DABUS case is a situation of a “sole inventor,” and this does not capture the full effect of any position on eliminating patents of which invention was completed (of at least in part) by AI.

Those who want to take the Ostrich Head in Sand approach (and not even recognize the issue) would leave us unprepared to deal with co-inventorship, where AI is ‘merely’ part of a team.

Would any such patents be tainted by the (intractable) presence of AI?

And of course, as I have also noted, whether or not patents to AI are permitted, we have an immediate issue with the (non-human, juristic person) legal concept of dealing with State of the Art.

We ALL should be wanting to resolve these issues sooner rather than later.

… apologies for sidetracking — the point of tending more may be seen to arise in situations in which that “taint” prevents any protection. In those cases, keeping the AI (and even the hint of involvement of AI) as Trade Secrets would be the norm, and the intent of the patent system (that wonderful Quid Pro Quo) would be hindered.

I have no idea whether DABUS did or did not “invent” the invention for which it is applying. The fact that Thaler is litigating DABUS’ entitlement to the patent essentially everywhere tells me that the whole project is really more about providing a test case for AI inventorship than it is about obtaining commercial exclusivity for business purposes.

Still and all, even if DABUS is more a stunt than a “real” patent application, it gives us a good occasion to consider an issue that we will have to consider eventually. In other words, even if DABUS did not really invent the claimed invention here, it will eventually arrive that AI invents, and it will not go amis now to consider how we should amend our statutes to deal with this coming reality.

The easiest way to solve these problems would be to amend Title 35 to match Title 17. That is to say, already our copyright laws consider that the company who employs some artists is the “author” of the artworks that those artists produce. We should similarly amend Title 35 to regard the company who hires the scientists / engineers / technicians as the “inventor” of the inventions that those employees conceive.

That way we would not need to sweat the question of whether DABUS or Thaler “conceived” this or that aspect of the claimed inventions. It would be enough to know that Dabus Corp. owns DABUS and employs Thaler. At that point, Dabus Corp. would be—legally—the inventor. Nice, easy, simple, and legally workable (as we know from long experience in copyright law).

I don’t think the solution for an AI inventor is to remove inventorship from individual inventors and instead award inventorship only to large corporations, of whom an individual employee who solely conceived of the invention is only a small part.

Employment should not negate an inventor’s contribution.

As for AI – someone has to interpret whatever the AI spits out. Until AI is capable of deciding how to draft and file its own patent applications, this is a non-issue aside from those who choose to make it an issue.

JaA

You no doubt are aware that the person who “decide[s] how to draft and file [the] patent application” is NOT the inventor, right?

As to the mere “open a box containing the invention of another” scenario, this runs into IMMEDIATE problems in a ‘blind test’ of not knowing who DID DO the inventing that another merely “opens the box” to.

Like it or not — going the Ostrich Head in the Sand route is not an option.

Employment should not negate an inventor’s contribution.

Why? What public policy purpose is served by distinguishing between an application conceived by Chris, Kim, & Pat (but owned entirely by Acme Corp.) and one conceived only by Chris & Pat (but owned entirely by Acme Corp.)?

Chris and Pat, at least in theory, have an opportunity to negotiate the terms of their employment. Making the employer automatically the inventor would take this power away and further empower the employer. I know that in reality, this doesn’t make much difference because assignment clauses are common in employment agreements, but I’m sure there are edge cases where this would make all the difference.

As I noted above, the amendment that I am proposing for Title 35 already exists in Title 17. In other words, if the problem that you hypothesize were real, it has had ample time to emerge and manifest. Can you point to real world examples of this putative phenomenon?

You mean besides what we see in the Big Entertainment industries…?

anon explained that corporate inventorship does not comport with the “terrain”.

A machine can’t invent. It can make it’s owner an inventor. Nor can it host an abstraction, but it can host an abstraction for its human user.

You go from plain weird to really bizzaro there Marty.

In your hurry to try to take a dig at me, you forget to have some cogent point to make.

In that hurry, you now seem to contradict the heart of your own “pet theory.”

(First, you completely miss the point here that a machine IS inventing)

Aside from that first item, you insist that “within a machine” there can be no “abstraction,” and yet here seem to be providing that a machine CAN have some abstraction, if but “for its human user.”

You make less sense than usual (and that’s no small feat).

Comments are closed.