by Dennis Crouch

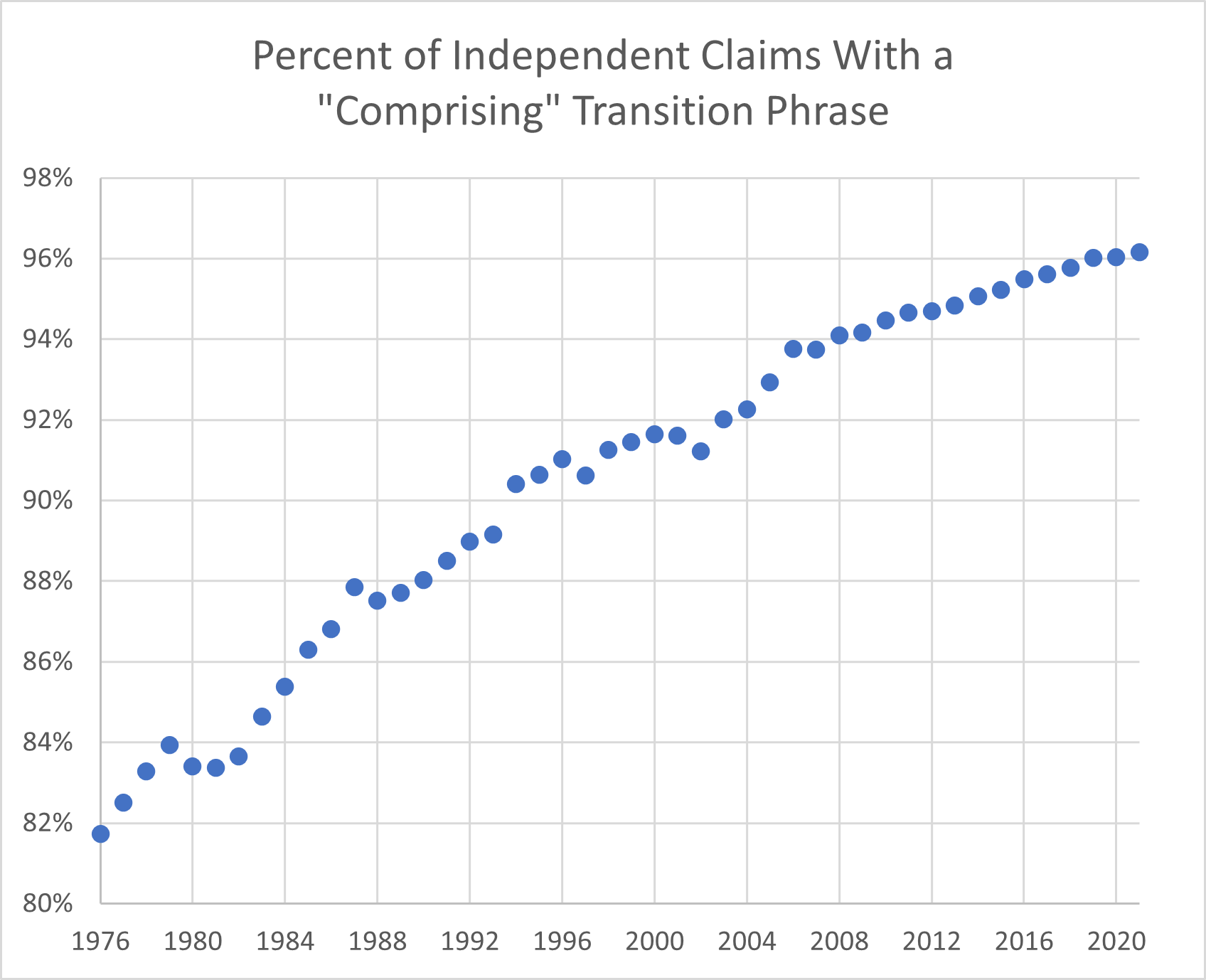

You may have heard that most US utility patent claims use the open transition phrase COMPRISING. Here’s the data to support that hearsay. The chart below shows data from independent claims gleaned from issued US patens grouped by patent issue year.

Patent courses traditionally talk about the three primary transition phrases:

- Comprising/Comprises/Comprised of (Open Transition)

- Consisting of (Closed Transition)

- Consisting Essentially Of (Hybrid Transition)

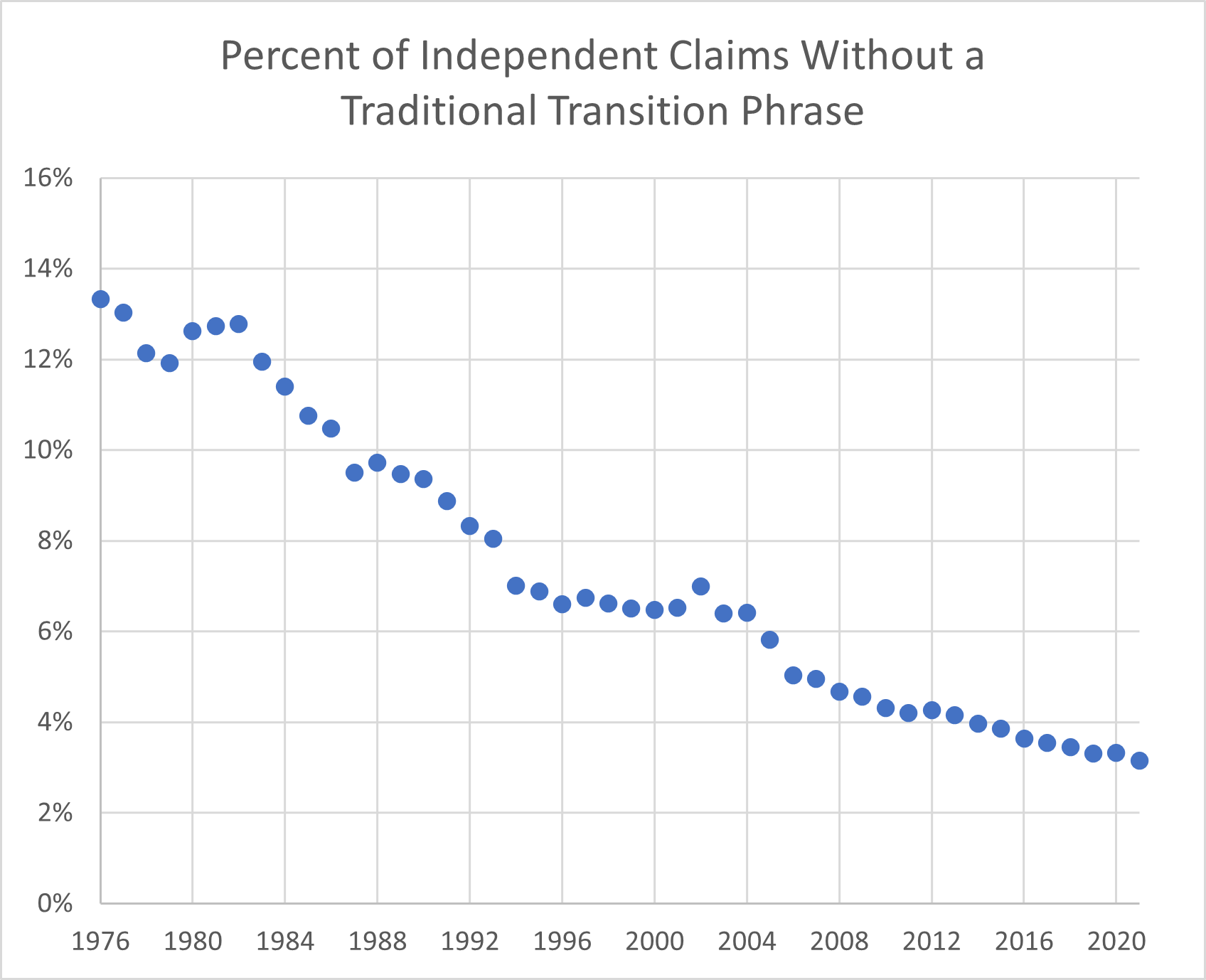

In recent patents, fewer than 1% of claims use “consisting of” or consisting essentially of.” Rather, the biggest non-comprising segment is the category of claims that lack any traditional phrase as shown in the chart below. These non-traditional claims might use the word “having” or “including” as a transitional phrase, or they might not use any word at all.

- One or more non-transitory, computer-readable media having instructions that, when executed by one or more processors, cause a device to: …

- A non-transitory computer-readable medium configured to store instructions that, when executed by one or more processors, cause the one or more processors to perform operations that include:

- A handheld, self contained, air cooled induction heater including …

- A compound or a pharmaceutically acceptable salt thereof, wherein said compound is: …

- A compound, or a pharmaceutically acceptable salt thereof, having the structure of

- A method, by one or more processors, for managing text in rendered images: [No transition at all except for a colon]

- Intermediate of formula B-20 [showing structural diagram of compound and going on to include several markush groups]

In many cases it appears that attorneys may be using the alternative transitions as part of their claim stratification strategy. Thus, many of the claims relying upon a non-traditional transition sit alongside other claims in the same patent that use “comprising.”

The transitional phrase is ‘configured to’

/I’m not putting the period inside, its dmb, no homo/

While not strictly a “transitional phrase,” I do wonder what the current trending graph for Jepson claims would look like.

As I recall, Dennis charted Jepson claiming decline a few years ago?

Yes, thanks Paul – you are correct.

It’s just been quite some time since that graph.

I am curious as to just how low a percentage of claims actually employ that format (and one of Malcolm’s recent whines were directed to that format at being “the right one” to be used — real data could show just out of touch Malcolm is on that point).

Is there any disadvantage to using “having” or “including” in claims instead of “comprising”? The former would make claims a little more readable to inventors.

The dictionary definition of “comprising” is broad enough to include “composing” and that is confusing for non patent attorneys.

Comprising in claims seems like a completely unnecessary anachronism.

“As a patent law term of art, ‘includes’ means ‘comprising.'” SanDisk Corp. v. Memorex Products, Inc., 415 F.3d 1278, 1284 (Fed. Cir. 2005)

In patent claims, I think it is more accurate to say that:

— includes isn’t a term of art and should be interpreted according to its dictionary definition

— comprising is a patent term of art that means includes (MPEP 2111.03) and it shouldn’t be interpreted according to its dictionary definition which allows a closed-ended interpretation

SanDisk is saying that includes means comprising which means includes. 🙂

It’s turtles all the way down.

(That’s how language works)

Jeffrey, to my way of thinking, the words “including”, “having”, “exhibiting”, “composed of”, “comprising”, “consisting essentially of” and “consisting of” all have different meanings. I for one should welcome it if patent attorneys drafting claims were all to be aware of it, and then advisedly to choose for their claim the word that is correct, for the meaning they wish to impart.

But meanwhile, I expect to see uninterrupted the practice of selecting “comprising” every time, if only because those are the instructions of the people who teach claim drafting.

Why do they teach that? Because, they suppose, you can’t go wrong if you choose “comprise”.

Why that? Because”comprise” is generic to BOTH “include” AND “consist of”. So use “comprise” to cover BOTH of these possibilities.

Except that, to everybody except claim drafting professionals, excessive use of “comprise” renders claim language silly, or unpalatable, or even indigestible. Brother and sister patent attorneys, for the reputation of our profession, this is unfortunate.

For example, compare:

1. A crash test dummy, including a head and a neck, and………

with

1. A crash test dummy, comprising a head and a neck, and…….

Do you, like me, find something wrong with the selection of “comprise” in 2? Why include in the claim the case of a crash test dummy which consists of a head and a neck?

“Brother and sister patent attorneys, for the reputation of our profession, this is unfortunate.”

There are FAR WORSE items to be concerned about.

I thought you would be mailing to reprimand me for using the expression”brothers and sisters”. Is that still OK, still PC?

But (no snark) I’m curious, anon. What are these “items” that are so much worse? Do you not agree with me, that it is a core competence of any patent attorney, in any jurisdiction, to be articulate and an expert communicator to a range of different readerships.

If my concern here is misplaced, where do you say it would be better placed?

I am the least “PC” of anyone around here.

As to the language, you are focusing on gnats of “ultra-precision.”

But the art of claim drafting includes being suitably vague at times.

Also, it would be error to think that terms used should sacrifice legal maneuvering for the mere sake of some unspecified “ease of reading to the common man” so as to avoid hurting the feelings of that person when they are reading a legal document.

You’re good for a laugh, anon. The high art of claim drafting includes being intentionally vague? That’s how they taught you, is it?

Perhaps in your jurisdiction, being deliberately ambiguous pays dividends. Like, claim construed widely against infringers but narrowly to see off validity attacks? Not so in the courts where I’m based, where the likelihood is the other way round. Which is a nasty consequence for the clients of those patent attorneys who regard writing claims that are deliberately ambiguous as the pnnacle of their professional skill set.

Which claim-drafting approach shall the courts encourage then: precision drafting, or drafting claims that are intentionally ambiguous?

Is this inclination towards deliberate ambiguity perhaps the “item” that you worry about, that you assess as “far worse”? If so, fair enough.

I did not say “deliberately ambiguous.”

I said “suitably vague at times.”

Or are you forgetting that the protection is supposed to extend some twenty years into the future (or perhaps you are one of those “exacting picture claim” kind of folk who give clients that are oh so easily avoided….

Several thoughts, anon:

1. You assert that it is good to be “suitably vague” when drafting a claim. But “vague” is a precise synonym for “indefinite”. Deliberately writing claims that are indefinite strikes me as risky, not the best way to serve the client.

2. Width of claim is not to be confused with vagueness. There is no need for vagueness to rise with increasing reach of the claim. The goal is to reach the full scope to which the inventor is entitled, in return for their enabling disclosure of their contribution to the art, in a claim that will resist all attacks on its validity, including that the claim suffers from some indefiniteness or other.

3. I had thought all this was self-evident to all readers here.

Obtuse. Is it deliberate?

(hint: I used the word “suitably” on purpose)

And clients do deserve more protection than what picture claims provide, would you not agree?

Thanks, Dennis. I’m curious – what was your data source?

Great. Here is a link to the USPTO Raw data:

link to patentsview.org

I ran these through a simple parsing program I wrote to make the charts.

It is a very beneficial article. I also wondered that what is the rate of working with a patent attorney among applications that don’t use traditional transition words? In Turkey, we may encounter miraculous claims in applications made without the assistance of a patent attorney.

Comments are closed.