Recently, a copyright infringement suit had been filed before the District Court, Trivandrum, against Facebook India. (CNR Number: KLTV010019372021) The reason for filing the suit was that certain unknown people had posted without authorisation original sound recordings created by Vempati Ravi Shankar (the plaintiff’s late husband) on the defendant’s social media platforms – Facebook and Instagram. Being his sole legal heir, the copyright in these works is held by Sweety Priyanka Vempati Ravi Shankar. (hereinafter Priyanka) She had notified Facebook and Instagram regarding the presence of infringing sound recordings on their platform, but they failed to takedown it down and hence, the present suit. On 2nd July, the court granted an ad-interim injunction in the plaintiff’s favour, ordering the takedown of the infringing content.

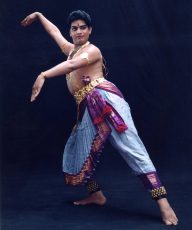

Before proceeding further, a brief profile of Vempati Ravi Shankar: He was a Kuchipudi artist who had participated solo in various national and international festivals and had been conferred with multiple titles and awards, such as ‘Kala Ratna’. He was the son and disciple of Padma Bhushan Vempati Chinna Satyam (a renowned Kuchipudi artist). He was credited with the creation of many musical compositions and choreographies.

A copyright holder has the exclusive right to communicate his work to the public and as the plaintiff’s sound recordings were used without authorisation, copyright infringement could be easily proved. In addition to copyright infringement, the plaintiff also claimed violation of moral rights and infringement of posthumous celebrity rights. In this post, I will explore the different considerations that the court might look into in reaching its decision about the above rights.

The Right to Integrity

Section 57 of the Copyright Act, 1957 provides for moral rights that vest with the author even when he assigns the other rights in respect of a work, and moral rights are of two kinds – the right to integrity (to prevent modification of the work which is prejudicial to the honour and reputation of the author) and the right to paternity (to claim authorship of the work). In the present case, people had been posting Shankar’s sound recordings accompanied by his name on Facebook and Instagram. So, violation of the right to paternity cannot be claimed.

Right to integrity stipulates that an action can be taken against ‘distortion, mutilation, modification or other act in relation to the said work if such distortion, mutilation, modification or other act would be prejudicial to his honour or reputation’. If the provision is read literally, based on the limited information regarding the posting of the plaintiff’s works, the moral right to integrity does not seem to have been violated in the present case.

If the phrase ‘other act in relation to the said work’ is interpreted expansively, the use of a sound recording by unknown persons for commercial purposes could come under the ambit of this section. Rishabh had earlier argued for a broader interpretation including ‘mere use’ within it, when a song for which Javed Akhtar had written lyrics was used in a new, political film. Here, use of a work means use in a manner not intended by the author, such as use by a political party. Nikhil has also considered how moral rights can be utilised for preventing misappropriation of songs for political campaigns.

If the concerned sound recordings have been used by competing artists, Priyanka could probably claim that the use in question is contrary to the manner that Shankar had intended his work to be used and thus, prejudicial to his reputation. But broad interpretations are problematic, as they could have a chilling effect on downstream creators.

Generally, where the question is regarding the determination of an act being ‘prejudicial to his honour and reputation’, one of two tests can be applied – 1) subjectivity test, wherein the author is required to establish infringement and 2) objectivity test, wherein the public opinion or experts are relied upon to prove infringement. In India, these tests have never been used, except in Amarnath Sehgal v. Union of India and even then they were not explicitly mentioned. Sehgal’s mural had been kept in a store room and he objected to such treatment of his work. If examined under the objective theory, he did not suffer any reputational harm, as the public could not see his work. But under the subjective theory, he suffered reputational harm, as his work had been damaged and was not available for the public to see. Thus, the court, by accepting Sehgal’s claim of violation of the right to integrity, had implicitly accepted the subjectivity test. (Prof. Basheer had discussed the above point regarding subjectivity and objectivity tests in a comment.) Even based on the subjectivity test, Priyanka will probably not be able to prove reputational harm.

Right of Publicity: Post Mortem?

India does not have codified law for publicity rights and the precedents are the only way to understand its origin, nature and scope. For establishing infringement of the right of publicity, certain requirements need to be fulfilled which have been given in Titan Industries v. Ramkumar Jewelers. They are: ‘Validity: The plaintiff owns an enforceable right in the identity or persona of a human being’ and ‘Identifiability: The celebrity must be identifiable from defendant’s unauthorized use’.

Late Vempati Ravi Shankar’s celebrity credentials will be hard to question. With his name being used with the infringing content, identifiability is also not an issue. The question is – can the right of publicity survive after an individual’s death? The jurisprudence concerning publicity rights for living individuals has been previously examined here, here and here. Let’s see what the various case laws pertaining to the posthumous survival of celebrity rights have held.

In 2010, in Kirtibhai Raval v. Raghuram Jaisukhram Chandrani the plaintiff (a descendant of late Jalaram Bapu) had claimed that Jalaram Bapu’s right to privacy and publicity would be violated if the defendants made a film about his life. The Gujarat High Court without any discussion about celebrity and privacy rights, granted an injunction stating that irreparable harm would be caused if these rights are violated.

In Akshaya Creations v. Muthulakshmi, the Madras High Court held that Veerappan’s widow does not have any right to privacy in respect of the film being made on Veerappan’s life, as the film is based on police records. Here, there was no discussion if privacy survives an individual’s death. (discussed here) In 2021, a position contrary to Kirtibhai was taken by the Madras High Court in Deepa Jayakumar v. A.L. Vijay. Here, the late Jayalalitha’s niece had claimed infringement of right to privacy, but was refused an injunction against the makers of a film and web-series based on Jayalalitha’s life. The court after examining precedents said that ‘“posthumous right” is not an “alienable right”’, and right to privacy ends after an individual’s death. Although these cases do not deal with publicity rights, their reasoning regarding right to privacy is useful for understanding the nature of celebrity rights, as right of publicity originates from the right to privacy.

Recently, in Krishna Kishore Singh v. Sarla A. Saraogi, the Delhi High Court rejected a temporary injunction application by late Sushant Singh Rajput’s father concerning the use of Sushant’s name, caricature, likeness in films being made on his life. Right of publicity was raised as one of the issues. The court examined relevant cases and held that celebrity rights ‘cannot be appreciated, divorced of the concept of right to privacy’ and that they originate from the right to privacy stemming from Article 21. Relying on Puttaswamy v. Union of India, that court decided that the right of privacy only exists during a person’s lifetime and ceases upon his death. Additionally, the court said that the issue of posthumous survival of celebrity rights ‘requires a deeper probe’.

The courts’ approach in Krishna Kishore Singh and Deepa Jayakumar is well-reasoned, and it’s clear that courts are not in favour of post-mortem survival of publicity rights. It is pertinent to note that in case of unauthorised biopics, books, web-series, etc., the enforcement of right to privacy and publicity is affected by the competing right of freedom of speech and expression. In R. Rajagopal v. State of T.N., the Supreme Court observed that when public records are used for depicting an individual’s life story, then violation of privacy cannot be pleaded against such use. This competing freedom was also recognised in Deepa Jayakumar and Krishna Kishore Singh.

It is well-established that the right to privacy begins when a person is born and ceases upon his death. The answer to the existence of post-mortem publicity rights depends upon the courts’ interpretation of its relationship with privacy. If considered separately, there might be scope for posthumous survival. And perhaps, they should be considered independently, as the nature of the rights is different. Right of publicity has a commercial aspect associated with it, which is lacking in case of privacy. A celebrity’s name, photos, music, etc. can still be utilised for merchandising, making movies or posters. The entire public’s memory about that celebrity is not collectively wiped off! Wouldn’t it be strange if tomorrow the unauthorised sale of miniature toys of Daler Mehndi is allowed just because he is no longer alive? (referring to the DM Entertainment v. Baby Gift House case, discussed here) The possibility of commercialisation associated with a celebrity’s name, photos, music, etc. doesn’t just evaporate all of a sudden upon their death and dead celebrities have generated millions of dollars for their heirs. They are even being resurrected to appear as holograms.

One way to separate publicity rights and right to privacy would be introducing a provision regarding publicity rights within the copyright statute. In New York (the state), publicity rights have been codified and survive after a celebrity’s demise.

Celebrity Rights as Property?

This question is quite relevant in the context of posthumous application of publicity rights. Because if it’s indeed property, then it will survive after an individual’s death. But if it’s a personal right, then it obviously ceases with the individual’s demise. In DM Entertainment, Daler Mehndi had assigned all his rights and interests in his personality to the entity, DM Entertainment. Does this assignment mean that his rights can be enforced by the entity even after his demise? The Delhi High Court referred to his personality rights as a ‘quasi-property’ right!

This stance is surprising in light of ICC Development v. Arvee Enterprises, wherein ICC’s claim regarding acquisition of personality rights had been rejected and the court held that ‘right of publicity vests in an individual and he alone is entitled to profit from it.’ (emphasis supplied) The court clearly said that personality rights are personal rights and cannot be transferred to non-living entities.

In Titan Industries, Mr. Amitabh Bachchan and Mrs. Jaya Bachchan were engaged in promoting and advertising Tanishq (a brand owned by the plaintiff) jewellery. The plaintiff sued the defendants when another jeweller put up hoardings that were exactly similar to the plaintiff’s hoardings featuring the Bachchans. One of the issues raised was the personality rights of the Bachchans and the plaintiff’s standing was based on an ‘Agreement For Services’ with the celebrity couple. Here, similar to DM Entertainment, another entity was allowed to enforce the celebrity rights of the individuals (the Bachchans). If someone can hold someone else’s personality rights, why can’t the legal heirs? (You can also read Arushi’s post where she has discussed in detail about the nature of celebrity rights.)

Many questions remain to be answered. Can publicity rights survive after a celebrity’s death? Are they personal rights or property? Is it fair to deprive legal heirs of the right to control and gain monetarily from the use of a dead celebrity’s name and persona? Seemingly, the invocation of moral rights and publicity rights might not work in favour of Priyanka. However, as she can claim copyright infringement, she will not face any trouble in enforcing her rights. But in certain circumstances, celebrity rights might be the only avenue available! And for those situations, the courts’ current stance could be a huge obstacle.

This is all not based on moral rights, Priyanka Vempati is Vempati Ravi Shankar’s wife and the LEGAL heir to all of their intellectual property. This is 100% legal and proper and not morally based.

Hi. I have not questioned the legitimacy of Priyanka’s rights as Vempati Ravi Shankar’s legal heir. I have mentioned in the beginning of the post that moral rights is one of the grounds claimed by the plaintiff. The other grounds claimed are copyright infringement and celebrity rights. (these have also been discussed in the post)

A really great and insightful post. I appreciate the links you have provided for further readings, thanks.

Thank you very much, Savan.