Instacart’s Privacy Policy Protects Stripe from Consumer Privacy Claims–Silver v. Stripe

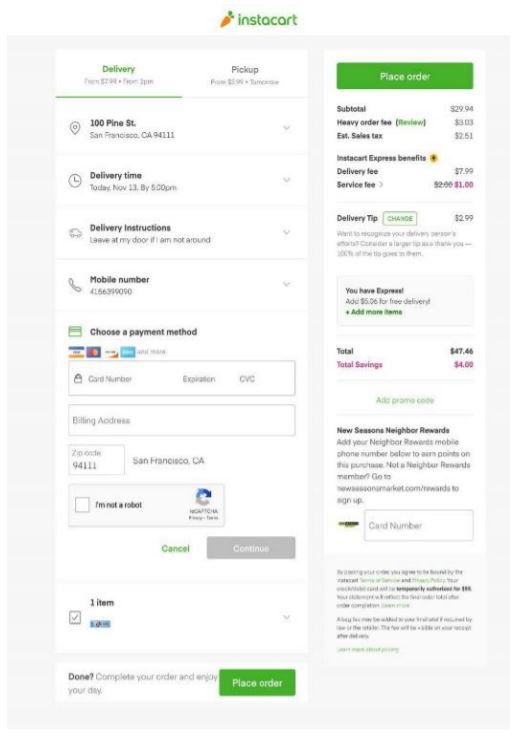

Instacart uses Stripe as a payment processor. Instacart purports to bind consumers to its privacy policy via this screen:

(Sorry for the poor image resolution. This is what the court’s opinion had. The applicable disclosures are in the bottom right of the screenshot).

(Sorry for the poor image resolution. This is what the court’s opinion had. The applicable disclosures are in the bottom right of the screenshot).

The court says Instacart creates an enforceable sign-in-wrap (ugh):

The Court finds Instacart’s privacy policy conspicuous and obvious for several reasons. First, the hyperlink to the privacy policy is displayed in a bright green font against a white background, which stands out from most of the surrounding text. Further, the hyperlink to the privacy policy is located close to the “place order” button, thus it is hard for a user placing an order to miss it. The bold font alerting consumers to the amount of the charge hold placed on their card calls additional attention to the area where Instacart’s privacy policy is located.

I personally think the court was pretty generous here. The applicable disclosures are to the right of the “place order” button, in a separate white zone, and the fonts referencing the privacy policy are the smallest on the page and smaller than the call-to-action associated with the “place order” button. However, consistent with Selden v. Airbnb, the green font for the privacy policy link is NBD. Instacart’s formation process leaves a lot to be desired; it (and Stripe) should be stoked that the judge bought it.

The court then holds that Instacart’s disclosures were sufficient to obtain consumer consent to Stripe’s activities:

there are provisions that disclose that third parties like Stripe may obtain not only credit card data, but also “identifiers, demographic information, commercial information, relevant order information, internet activity, geolocation data, sensory information, and inferences.” There are also provisions that disclose that Instacart’s “partners”—again without limitation—“use various technologies” to “collect information about your online activity over time and across different websites or online services.” These terms plainly disclose that partners like Stripe may install tracking software to collect data concerning users’ activities across websites….the privacy policy here clearly discloses the challenged conduct—that third parties like Stripe may collect and use a consumer’s sensitive data, including one’s financial information and web activity

It doesn’t matter that Instacart, rather than Stripe, made the applicable disclosures. Cites to Perkins v. LinkedIn and Javier v. Assurance. It also doesn’t matter that Instacart’s disclosures used the discretionary permissive term “may.”

BONUS: the court rejects the 17200 claim predicated on the CCPA: “as Stripe correctly notes, the CCPA has no private right of action and on its face states that consumers may not use the CCPA as a basis for a private right of action under any statute.” It’s pretty embarrassing for plaintiffs to try this 17200-bootstrapping-CCPA argument given the CCPA so clearly rejects this (one of the only places where the CCPA is actually clear).

Case citation: Silver v. Stripe Inc., 2021 WL 3191752 (N.D. Cal. July 28, 2021)