by Dennis Crouch

In a highly anticipated en banc decision, the Federal Circuit has overruled the longstanding Rosen-Durling test for assessing obviousness of design patents. LKQ Corp. v. GM Global Tech. Operations LLC, No. 21-2348, slip op. at 15 (Fed. Cir. May 21, 2024) (en banc). The court held that the two-part test’s requirements that 1) the primary reference must be “basically the same” as the claimed design, and 2) any secondary references must be “so related” to the primary reference that features from one would suggest application to the other, “impose[] limitations absent from § 103’s broad and flexible standard” and are “inconsistent with Supreme Court precedent” of both KSR (2007) and Whitman Saddle (1893). Rejecting the argument that KSR did not implicate design patent obviousness, the court reasoned that 35 U.S.C. § 103 “applies to all types of patents” and the text does not “differentiate” between design and utility patents. Therefore, the same obviousness principles should govern. This decision will generally make design patents harder to obtain and easier to invalidate. However, design patents will likely continue to play an important role in protecting product design.

In place of Rosen-Durling, the court adopted the analytical framework for design patent obviousness already outlined for utility patents by Graham v. John Deere Co., 383 U.S. 1 (1966) and supplemented in KSR. Judge Lourie’s additional views acknowledged that design patents obviousness involves distinct considerations (compared with utility patents), including the overall appearance, visual impressions, artistry, and style of ornamental subject matter. It remains to be seen whether those traditional design patent considerations will continue.

As a reinterpretation of the law, the case will have immediate effect — applying to all pending design patent applications as well as those already issued.

Key Analogous Art Requirement

A key limiting feature of the obviousness analysis is that the doctrine only considers “analogous” prior art. In utility patents, the test for analogous arts has two prongs, with the reference qualifying as prior art if either prong is met:

- Whether the prior art is from the same field of endeavor as the claimed invention, regardless of the problem addressed by the reference.

- If the reference is not within the field of the inventor’s endeavor, whether the reference is still reasonably pertinent to the particular problem with which the inventor is involved.

The general rational for limiting prior art here is that a person of ordinary skill would only look to certain areas and not consider every teaching in every art — and that allowing a broader lookback would too easily open the door to hindsight bias. These same hindsight bias concerns exist for design patents. With utility patents, it generally takes some amount of engineering to combine together two disparate teachings, but for designs it is often a very simple endeavor to combine portions of two designs.

In this its en banc decision, the majority held that for design patents, the analogous art certainly includes prong 1 – “art from the same field of endeavor as the article of manufacture of the claimed design.” On this point, the court appears to reiterate that the “same field” requires “the same article of manufacture or of articles sufficiently similar that a person of ordinary skill would look to such articles for their designs.” Quoting Hupp v. Siroflex of Am., Inc., 122 F.3d 1456 (Fed. Cir. 1997).

However, the majority declined to fully delineate how problem-focused prong 2 translates to designs, leaving that for future cases. While utility patents can generally be seen as solving a problem, design patents often do not address a “particular problem” in the same way. Further, unlike utility patents, design patents do not have written claims or descriptions that clearly define the problem being addressed. As the court noted, “a design patent itself does not clearly or reliably indicate ‘the particular problem with which the inventor is involved.'” Without this clear framing of the problem, it is more difficult to assess whether a prior art reference is “reasonably pertinent” to that unstated problem. In the briefing and oral arguments, there were even further arguments about whether ornamental designs for articles of manufacture could even be viewed as solving a “problem” at all – certainly not in a way that is directly translatable from utility invention law. But, by declining to set forth precise contours for applying the “reasonably pertinent” prong to designs, the court left room for future cases to further develop the analogous art test as it relates to the unique nature of design patents on a “case-by-case basis.

Identifying a Primary Reference

While rejecting Rosen‘s “basically the same” test for the primary reference, the decision still indicated that the obviousness analysis will ordinarily begin with a primary reference that is “the closest prior art, i.e., the prior art design that is most visually similar to the claimed design.” In re Jennings, 182 F.2d 207 (CCPA 1950). The result then is that we have a shift, albeit controlled, in the obviousness inquiry to a more holistic assessment based on the perspective of the ordinary designer, without requiring an extremely high threshold of similarity between the primary reference and the claimed design. Secondary references need not be “so related” to the primary reference, but must still be analogous art. In addition, there must be some reason for an ordinary designer to combine the references to create “the same overall visual appearance as the claimed design.” Of course, as with utility patents common sense can serve as the reasons.

Whitman Saddle and Flexibility

The court found support for its new fairly flexible approach in the Supreme Court’s 19th Century design patent obviousness analysis in Whitman Saddle. There, the Court held it was obvious to combine design aspects of two known saddle references to arrive at the claimed saddle design. Importantly, the Whitman Saddle Court did not require either prior art saddle to be “basically the same” as the claimed design, nor did it ask if they were “so related” that features from one suggested incorporation into the other. Rather, the Supreme Court focused on whether an ordinary artisan—a “saddler” or skilled workman in that field—would have combined the references based on the “customary” industry practice.

Rejecting Bright-Line Rules

More broadly, the majority opinion reflects the Supreme Court’s oft-stated aversion in KSR to bright-line rules that constrain the obviousness analysis. “Rigid preventative rules that deny factfinders recourse to common sense” when assessing obviousness are improper under § 103. The court explicitly rejected GM’s the government’s argument that eliminating Rosen-Durling would create a “rudderless free-for-all” or undue “confusion.” And here, the continued requirement of a primary reference will certainly help stay the course. (Minor correction above, it was GM who made the rudderless argument.) At oral arguments, the government reiterated that “it is important for examiners to be able to start with a primary reference.”

Concurrence Favoring Modification over Overruling

In a concurring opinion, Judge Lourie agreed that the Board’s decision should be vacated, but wrote separately to disagree with overruling Rosen and Durling outright. While acknowledging that the “must” and “only” language in those cases could be seen as overly rigid post-KSR, Judge Lourie advocated simply modifying the Rosen-Durling framework by replacing rigid terms like “must” with more flexible ones like “generally” or “typically.” Judge Lourie emphasized that Rosen and Durling originated from highly experienced judges well-versed in patent law obviousness principles. He argued the majority went too far in decisively overruling these “basically correct” precedents when a lighter touch of modification would have sufficed.

Secondary Considerations Unaffected

The court did not disturb existing precedent on consideration of objective indicia of non-obviousness, like commercial success and copying, in the design patent context. Commercial success, industry praise, and copying may demonstrate non-obviousness, but the continued relevance of factors like long-felt need was left for future cases. Similar to Prong 2 of the analogous arts test, the majority wrote that “It is unclear whether certain other factors such as long felt but unsolved needs and failure of others apply in the design patent context.”

= = =

In this case, LKQ Corporation and Keystone Automotive Industries, Inc. (collectively “LKQ”) filed a petition for inter partes review (IPR) challenging the validity of GM Global Technology Operations LLC’s (“GM”) U.S. Design Patent No. D797,625, which claims a design for a vehicle front fender used in the 2018-2020 Chevrolet Equinox. LKQ wanted to make replacement parts without obtaining a patent license and argued the claimed design was unpatentable as anticipated under 35 U.S.C. § 102 based on the Lian reference alone or as obvious under 35 U.S.C. § 103 based on Lian alone or Lian in view of a Hyundai Tucson reference.

The PTAB sided with the patentee and held that LKQ failed to establish by a preponderance of the evidence that Lian anticipated the claimed design under § 102. On obviousness, the PTAB applied the long-standing Rosen-Durling test. Under step one, the PTAB found Lian did not create “basically the same” visual impression as the claimed design, ending the analysis without reaching step two. LKQ appealed to the Federal Circuit, arguing that KSR overruled or abrogated the Rosen-Durling test. The original Federal Circuit panel affirmed the PTAB decision, holding it was bound by Rosen-Durling absent clear direction from the Supreme Court. The panel also affirmed the PTAB’s anticipation finding. The full Federal Circuit then granted en banc rehearing. On rehearing, the en banc Federal Circuit has affirmed the PTAB’s anticipation ruling but vacated and remanded back to the PTAB for a new obviousness determination.

Any bets on the viability of that wavy line design patent after this case? Seems like the coffin is built to spec and all that’s left is the nails.

BTW, I think the Fed. Cir. was partially incentivized to go all the way to en banc fully dumping that old CCPA Rosen design patent 103 decision by knowing that the present Sup. Ct. majority is generally in favor of strict literal statutory language construction [as I had been arguing] [versus judicially-generated special favors or exceptions, like Rosen]. Thus, risking another Sup. Ct. reversal if deciding to the contrary.

I am also looking forward to “Perry Saidman’s expert opinion and analysis,” as Perry, as a long-standing and experienced design patent law expert, is far more qualified to discuss the actual impact of this decision.

“the present Sup. Ct. majority is generally in favor of strict literal statutory language construction” except when they aren’t. They ignore the first part of this:

A well regulated Militia, being necessary to the security of a free State, the right of the people to keep and bear Arms, shall not be infringed.

They ignore anything that is not what they think the law should be in their conservative sense.

Oh please.

No one is 1gn0ring anything.

Indeed, they dismissed the Consititutional “well regulated Milita” as mere introductory surplusage like some claim preambles are treated.

Treated appropriately – you forgot that important point.

This is well understood.

Billy luvs to fondle his gun. Makes him think of the Framers and their high ideals.

Keep on Sprinting Left there, Malcolm.

Besides Perry’s analysis below, here’s another one, noting how advantagous for lawsuits design patenting had become:

link to ipwatchdog.com

When I was a utility patent examiner, the design patent people I trained with hated the Rosen decision and didn’t think it made much sense. It is sad that it took 20 years for progress to occur in the case law, but slow progress is better than no progress. Given that IP is 90% of the value in the US economy, you would think Congress would put more emphasis on keeping IP law up to date. Given the huge verdicts for design patents and the renewed interest, the CAFC finally did something right. Hallelujah!

My not-so-slight adjustment:

“Given that IP is 90% of the value in the US economy, you would think Congress would

not have attempted to shoehorn a non-utility patent into a utility patent system.”

Not sure what your point is anon? The overturning of the Rosen decision will get rid of a lot of (bad) design patents that shouldn’t be in the utility patent system. If Congress had been more on the ball then less design patents would have been shoved into the utility patent system by the Rosen ruling. I guess you take issue with even the existence of design patents. Call me crazy, but I have respect for industrial designers and think their work needs IP protection too.

My point is that NO design patent should be in the Utility patent system.

While I can fairly guess the stand that will be taken, I am very much looking forward to Perry Saidman’s expert opinion and analysis.

Here you go:

link to designlawperspectives.com

This:

“The Court cited the two-part utility patent test to determine the scope of analogous art: (1) whether the art is from the same field of endeavor as the claimed invention; and if not then (2) is the reference still “reasonably pertinent” to the particular problem with which the inventor is involved. (emphasis added). ”

As you note, this should be a null set, since design patents are expressly not to protect utility, and it is utility that solves problems.

(I also like how you reference In re SurgiSil)

Re your provided analysis at:

link to designlawperspectives.com

Thanks Perry

Paul, I have to acknowledge your unstinting support for incorporating KSR into design patent law. We have been sparring on this for awhile, and you win! The dark side is that the LKQ decision provides no real guidelines for determining design patent obviousness. We’re back to the Wild West – and I’m unable to advice my clients regarding the validity of their design patents. It’ll be interesting to see how the PTAB handles the remand (I’ll stick my neck out – the Board will find GM’s patents obvious).

And on the question of taking the LKQ decision to the Supreme Court, it’s not going to happen. LKQ got everything it wanted from the CAFC, and GM has no chance of getting a SCOTUS review. After all, the Federal Circuit’s opinion could have been written by SCOTUS. Perhaps that’s why the CAFC came out the way they did, not wanting to be slapped down by SCOTUS (again). For me, it’s too bad more of the judges could not sign on to Judge Lourie’s logical and centrist position. And boy, do I miss Judge Newman 🙁

Pyrrhic victory and “lose for winning” are what come to mind.

“ I’m unable to advise my clients regarding the validity of their design patents. ”

People actually pay you to advise them on design patent validity?

LOL

No one is surprised by your empty ad hominem, Malcolm.

Thanks Perry, and I agree with almost all of your 9.1.2.1. above as well as most of your cited new article. Especially agreeing that this Fed. Cir. opinion was carefully written to be Sup. Ct. “reversal proof” as noted at 11 above with the same motivation thought.

However, the new 103 “Wild West” you note for design patent obviousness is less wild in now having the large body of Utility patent decisions on obviousness under KSR to to look to.

However, as I also argued, I think there is another “wilding” 103 issue not even addressed in this decision. Namely, who or what is the correct 103 POSITA in a given design patent application or design patent lawsuit? Including the extent of his, her or its KSR common knowlege? Unlike many Utility patent case POSITA’s, who are usually technical specialists in a particular product line, my limited experience with design patents is that many designers of product shapes or other ornamental features these days are expert generalists that design the features of a wide variety of very different products. Should not that kind of a POSITA, unique to design and plant patents, logically impact the now-open question of what prior art is or is not non-analogous in design patent cases?

It IS Wild West for the reasons given: there was a direct PUNT on the part of “solving a problem” that speaks directly to Utility patents (that is, having utility) that is outside the domain of Design Patents.

The “problem” is coming up with a design that isn’t obvious.

You are right again, Paul. I believe that there are a lot of designers who are generalists – where do they look for motivation when they design a new gizmo? Probably everywhere, not at all limited to the article of manufacture at hand. Results? A lot of 103 invalidity holdings, a lot of PTAB decisions affirming examiners’ 103 rejections. And a lot fewer design patent applications as clients will be reluctant to roll the dice on anything but their most important designs.

One limitation affecting examiners is that they do not have the resources to develop “record evidence”, i.e., declarations by designers, about the field of analogous art. But patent applicants do have such resources to rebut 103 rejections. Let’s keep a close eye on how the PTAB handles the LKQ remand.

One possible solution – and I’ve been beating this drum for a long time. Adopt a two-tier design registration system, a la the European system, with a twist. Allow quick and cheap design registrations without examination. This will only protect against actual copies of the design, a la copyright. But, for the most important designs, give the applicant a two-year window to convert its registration into a design patent application with full examination. These applications/design patents can be subject to oppositions filed in the PTAB. I wrote a long post about in my blog last year and will be updating it soon. link to designlawperspectives.com

In fact, there is already a design registration law on the books that can be easily amended to include all industrial designs. The Vessel Hull Design Protection Act (VHDPA) is a federal law that protects the original designs of boat hulls by amending copyright law. It was signed into law in 1998 and is part of Title 17, Chapter 13 of the United States Code. Maybe 15 years ago, I actually drafted legislation that amended the VHDPA to include designs. It didn’t get much traction, because nearly all of the design patent practitioners basically said let’s go with the devil we know (design patents) rather than the devil we don’t know (design registrations). I don’t think that logic holds post-LKQ where the devil we know has now headed straight to Vegas.

How about we just move “ornamental” out of the utility patent system?

It was never a good fit anyway.

Agreed, anon. “Ornamental” was included in the early 20th century legislation when most designs had true ornament, e.g., embrodered sheets, drapes, silverware, plates, etc. It is rather archaic, and BTW not in the VHDPA or in my amended bill.

I don’t work in the design registration field but I wonder whether there are any penetrating criticisms yet, of the by now well-established EU design protection space (25 year term design registration rights and 10 year unregistered design right protection). As far as I know, the only one is that while the edifice of enforceable rights was conceived as a potent but cheap shield for use by EU-domestic designers it has been captured largely by American and Asian designers, who have proved to be rather more diligent and assiduous than domestic European industry in protecting in Europe their valuable design IPR. Does American industry in general realise what an attractive blueprint the EU design rights system provides?

What’s your experience, Perry?

Max III, I don’t have a single client who would rather pursue country registrations rather than an RCD. It’s very inexpensive, and provides broad rights, even if unexamined. I’m unaware of statistics regarding enforcement actions by US companies, or invalidity proceedings, except for one or two cases of my clients. And I’m particularly unaware of stats regarding unregistered design rights, probably because they are unavailble to US designers.

As noted above in my comment 9.1.2.1.3.2, I have been a long-time advocate of the US adopting a similar registration scheme, which in the past has fallen on deaf ears, but may garner new support in light of LKQ.

This from WolfGreenfield: “Design patent applicants facing obviousness rejections can still utilize non-analogous art arguments against prior art. Choosing a strategic title for the design patent application can help with such arguments.”

(That “whoosh” you hear being generated from all those title-change amendments.)

. . . and lookie there — design patent Examiners (understandably) cursing the CAFC for piling more work on their collective plates. Including looking forward with baited breath for the new guidance the Office comes up with.

This tactic is assuming that those prior recent [NOT en banc] CAFC decisions providing extreme prior art limitations from a design patent’s stated intended use or field will not be reconsidered in view of this en banc decisions discussions of non-analogous art tests for design patents, noted at 4.2 here and otherwise.

Let’s test this tactic after this LKQ Corp. en banc decision with important known prior examples that never got properly addressed. E.g., how widely would same-shape beveled corner prior art be excluded as non-analogous art after this LKQ Corp. en banc decision just by labeling the design patent a “smartphone” when that design patent shows only a beveled corner in solid lines in the patent drawing? Including now asking about the designer-POSITA’s “common knowlege” now that KSR is being applied instead of being ignored?

P.S. I am also ignoring here any possible argument that adding a claim-narrowing term by amendment to a design patent is “new matter”

Certainly, changing a critical element such as the item to which a ‘design in the abstract’ is applied to constitutes a major change in design patent claim scope, and support in the as-filed application will not be there for most all cases.

(But this only more emphasizes my comments below).

Blockhead practitioner “solutions” like this, intended to rescue a design patent that should never have been filed in the first place, are doomed. All they do is further rot the system by exposing the crass desperation of the worst rent-seekers.

A propos #8, may I ask, is it the spell check, or what, that presents “‘bated breath” as “baited breath”? No rush for an answer though: I’m not holding my breath.

Whatever, I do still smile, every time I contemplate how one goes about baiting one’s breath.

Well Max, I suppose I could blame it on spell check . . . or claim that one has baited breath after eating too many small fish (anchovies perhaps?) in the hopes that doing so would catch you a spouse . . . but no; in this case it was just me making a mistake.

Thankfully you didn’t hold your breath. 🙂

On a related note, the USPTO Office of Enrollment and Discipline is reporting that only three people have a design patent practitioner number to date.

Commercial success did not help GM, but maybe GM did not assert commercial success. Practically, since designs are examined quickly, and commercial success evidence generally takes time to develop, I am not sure if commercial success is a viable rebuttal to an obviousness rejection during prosecution. On the plus side, I do not recall ever getting a 102 or a 103 rejection in a US design case. Lots of 112 rejections, though. Willl have to see if the US patent examiners want to slow down their dockets with more office actions and Examiner’s Answers. Maybe filing designs in multiple jurisdictions is necessary to slow down wholesale copying of commercially valuable, aesthetic inventions. Maybe narrower claims, too. Good luck to newly minted design-only patent practitioners. In re Owens already makes the process of securing meaningful design protection more sporting. Now this.

“ Maybe narrower claims, too.”

LOL

Only the USA conflates industrial designs with patents for inventions. This decision is another step in the wrong direction. I don’t expect Congress to separate designs from patents, but it should. Sometimes other countries know what they’re doing.

What is the point of having a Register of Designs? Is it to promote the progress of useful arts, or might there be some other reason, closer to copyright law that utility patent law. I mean, anon below just observed that there is no “utility” requirement for design patents so why should there be a requirement that they must also be non-obvious?

Is this not just another example of Fed Ct mischief-making and pot stirring?

Right, MD. See my comment 9.1.2.1.3.2 about moving design protection to the Copyright Office…

“ I don’t expect Congress to separate designs from patents, but it should.”

Narrator: Whatever Congress does will be disliked one hundred times more intensely than the status quo.

After years of complaining on this blog about the CAFC ignoring KSR 103 law re design patent cases, and design patent expert’s [I am not] denying it’s relevance to a prior old CCPA case, we finally have my legally obvious view sustained that 35 U.S.C. § 103 “applies to all types of patents” and the text does not “differentiate” between design and utility patents. Therefore, the same obviousness principles should govern.”

This decision* adds that: “Under the Patent Act, the statutory provisions “relating to patents for inventions,” or utility patents,“shall apply to patents for designs, except as otherwise provided.” Id. § 171(b).”

*LKQ Corp. v. GM Global Tech. Operations LLC (Fed. Cir. May 21, 2024) (en banc).

I was also pleased to see this language in the opinion, because the Fed. Cir. has yet to face the fact that these days the proper 103 POSTA for many design patents may be a professional product designer who works on a wide variety of products:

“In this opinion, we do not delineate the full and precise contours of the analogous art test for design patents. Prior art designs for the same field of endeavor as the article of manufacture will be analogous, and we do not foreclose that other art could also be analogous. Whether a prior art design is analogous to the claimed design for an article of manufacture is a fact question to be addressed on a caseby-case basis and we “leave it to future cases to further develop the application of this standard.”

Objectively, why would a Person of Ordinary Skill In The Art be a professional designer (who is more of an expert than an ordinary person) as apposed to an ordinary user?

Separately, your notion of ‘across all fields’ appears to be in direct conflict with the more recent emphasis of the criticality of that portion of the design patent claim that was to the particular item to which any ‘design in the abstract’ is being applied to.

One does have to wonder if the courts are purposefully creating Gordian Knots.

Yes there is some other prior recent [NOT en banc] CAFC confusion about extreme prior art limitations as to a design patent’s stated intended use or field which should be reconsidered in view of this decision. But the 103 POSTA has never been a “user.”

That doesn’t really address why one would want an expert as the Person of Ordinary Skill.

Also, not sure that your “spin” down-playing the critical (well, until recently) PART of the design claim as being ‘merely’ “stated intended use or field” given that such does make the critical distinction between a ‘design in the abstract’ and a protectable design.

Let’s not dismiss this ‘object to which a design is affixed’ as having (literally or figuratively) NO weight.

… my view also ties to the judicial applications of “ordinary observer.”

BTW, this decision partially answers the second question of my case note on a confused case published by Dennis on this blog: ““Design Patents §103 – Obvious to Whom and As Compared to What?” Patently-O, Sept. 17, 2014.” But not the first question, referenced in comment 4.2 here.

Nor does this decision address the legally inconsistent [in my view] way in which design patent infringement is determined as compared to utility patents, including prior art changing a flexible claim scope interpretation. Maybe I will still live long enough to see someone also challenge that on a statutory basis?

If references are not important (and I doubt that having a “primary” is going to do much of anything), then what we really are talking about are designs ‘in the abstract’ or untethered to the item of manufacture (but only in a negative, no-design-patent-for-you manner).

Can’t read, “designs in the abstract,” without wondering whether the CAFC’s (or later, SCOTUS’) next move is to find some way to rule designs ineligible for patenting under . . . under . . . under . . . 101!

Well, certainly they expressly lack utility…

True dat. O’ course, these two courts have nooooo problemo making stuff up out of thin air (including usurping Congress when needed) to reach their desired ends.

I suppose the good news is that manufacturers might start making interesting cars again. Maybe even in smaller sizes, since it’s easy enough to slap on a minor design modification on all the behemoths that currently swarm the roads. On the other hand, design patents aren’t utility patents for a reason. This goes too far, and I agree with Lourie. On the other other hand, if 2 references is a good limit for design patents, then maybe we need to revisit the “no maximum” rule for utility patents. On the other other other hand, KSR pretty much turned obviousness (at least for examination, for at least some arts) into a rudderless free for all for utility patents, so why would we expect a different outcome for design patents?

wrong. Graham v Deere still applies. All KSR did was delete the TSM test as a requirement for motivation to combine. The motivation to combine could come from other factors outlined in KRS (e.g., market forces, a finite number of predictable solutions). KSR didn’t do away with Graham v. Deere. So there is nothing at all wrong with the legal framework. If patent examiners don’t know how to apply that framework, that needs to be fixed through training, but doesn’t mean that KSR was somehow wrongly decided

How often are the Graham Factors explicated in Office Actions (sufficiently)?

I look forward to see how the USPTO comes up with an analysis for the Examiners to determine the “ordinary designer”. Just as I am still looking forward to seeing the USPTO come up with an analysis for Examiners to explicitly determine the level of ordinary skill in the art or explain why a reference itself reflects an appropriate level of skill.

I’m not wrong. But you would have recognized that if you read my whole comment instead of itching to get your comment in. Stick to the ball court because the other kind requires more consideration before responding.

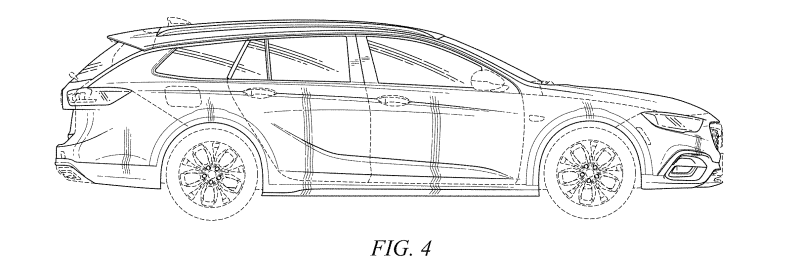

Note – the design patent image above is from a GM car, but not the one at issue here. I used it because it provides the whole visual for the vehicle while the patent at issue here is simply one bit of the fender and isn’t very interesting looking (which may be why it was challenged as obvious).

The Chinese are going to love this decision.

Yup. All car makers better beef up their design legal eagle team, because they’re going to need it. (Sorry; all Summer vacays are now on hold.)

How nice of the CAFC to blow a hole in settled law . . . while leaving important questions for other days.

Fun times just ahead. Including withdrawn allowances + new PTO rejections in 3 … 2 …

One could not have found a better fact case in which to successfully challenge design patent 103 case law than a widely needed car fender replacement part [which must match the shape and appearance of the original part]. Design patents on that particular product were already under attack in proposed legislation as imposing a major consumer cost burden.

There really is no such thing as “must match,” now is there.

Want to match, sure.

“Must” is only from a functional aspect, and that is not what designs provide.

How many weird car owners would allow a damaged car fender [typically subject to a car company design patent] to be replaced with a fender of such a different shape that it would not infringe the design patent and thus be weirdly different in appearance from the fender on the opposite side of the car? [One can only imagine how such a weird looking car would sell as a used car.]