A federal court has shot down a copyright infringement lawsuit claiming that Top Gun: Maverick flew too close to a 1983 magazine article that inspired the original film.

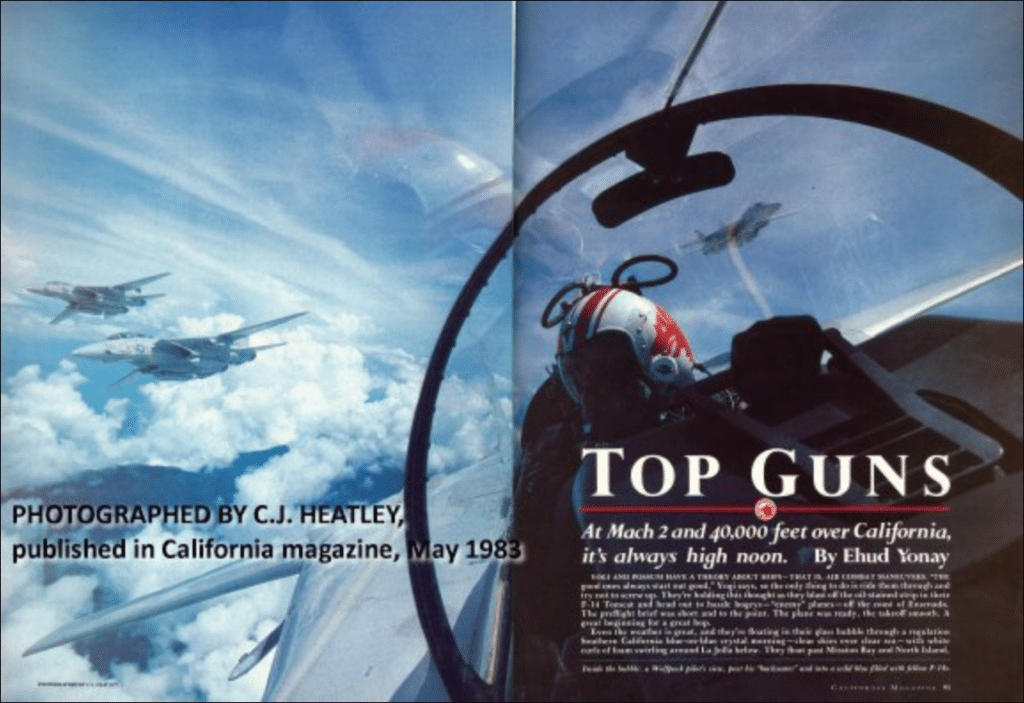

A California federal judge has permanently grounded a copyright infringement lawsuit filed by the heirs of Ehud Yonay, the writer whose 1983 article in California Magazine inspired the original Top Gun film. Yonay’s widow and son launched the legal action in June 2022 after Paramount Pictures released the blockbuster sequel Top Gun: Maverick without renegotiating a license to adapt Yonay’s “Top Guns” article, despite a 2018 copyright termination notice served by his heirs.

The studio maintained that a new license for the article was unnecessary, since Maverick is a fictional work that shares no significant similarities with Yonay’s article other than uncopyrightable facts about the Top Gun program and its pilots. Following discovery and armed with expert witnesses, the parties filed dueling motions for summary judgment last November. In a ruling issued late Friday night (read here), Central District of California Judge Percy Anderson granted Paramount’s motion, denied the plaintiffs’ motion, and entered judgment in favor of Paramount.

The Court’s Ruling

At the heart of the court’s ruling was Judge Anderson’s application of the Ninth Circuit’s so-called “extrinsic test,” which requires courts to compare objective similarities between protectable elements of two works—plot, themes, dialogue, mood, setting, pace, characters, and sequence of events—after “filtering out” unprotectable elements. This means ignoring similarities in historical facts, general plot ideas, and scènes à faire (situations that flow naturally from a basic plot premise), all of which aren’t protected under well-established copyright law.

Battle of the Experts

As I’ve written before, several Ninth Circuit panels in recent years have advised district courts to exercise caution in dismissing copyright cases alleging substantial similarity without first permitting discovery and expert testimony. For example, in one recent unpublished opinion involving the Apple TV+ series Servant, the court of appeals encouraged the use of expert witnesses to help district judges evaluate similarities in cinematic techniques, distinguish creative elements from unprotectable scènes à faire, and determine the extent and qualitative importance of similar elements between two works.

After Judge Anderson allowed the Yonay case to proceed past the pleading stage, the parties designated dueling experts. The plaintiffs enlisted writer and professor Henry Bean to opine on the similarities between Yonay’s article and the sequel film. However, the court criticized Bean for failing to differentiate between protectable and unprotectable elements of the two works (e.g., facts) in his analysis, and for relying on subjective comparisons of the works. These flaws rendered Bean’s opinions “unhelpful and inadmissible,” resulting in the court excluding his expert report.

Judge Anderson was more complimentary of Paramount’s expert Andrew Craig, a Commanding Officer in the Navy Reserve and former Top Gun instructor. Craig opined that Yonay’s article accurately described the Top Gun program and the experience of flying a jet fighter, which the court found helpful in filtering out the unprotected factual elements contained in the two works.

No Substantial Similarity of Protectable Expression

The court’s exclusion of “facts” from the substantial similarity analysis was particularly important to its ruling, as Judge Anderson acknowledged that Yonay’s article and Paramount’s film both feature the Top Gun flight school and chronicle fighter pilots training and embarking on missions. However, because Top Gun is a real fighter pilot school and the graduates and instructors discussed in Yonay’s article are real people, those similarities were excluded from the court’s comparison, as was dialogue that the article presented as “real statements made by actual people.” Other similarities that flowed naturally from the basic premise of the works—fighter pilots landing on an aircraft carrier, being shot down while flying, and carousing at a bar—were also excluded as “unprotected facts, familiar stock scenes, or scènes à faire.”

Focusing only on the protectable elements, Judge Anderson concluded that Yonay’s article and Paramount’s Maverick sequel weren’t substantially similar under the extrinsic test, entitling Paramount to summary judgment on the plaintiffs’ copyright infringement claim. The court also granted summary judgment in favor of Paramount on the plaintiffs’ claim for breach of contract, ruling that since the sequel wasn’t produced under the original assignment of rights in Yonay’s article and didn’t infringe the article’s copyright, Paramount wasn’t obligated to credit Yonay on the new film.

The Bottom Line

While the Ninth Circuit has touted the value of expert witnesses in several of its recent (albeit unpublished) opinions, Yonay v. Paramount Pictures is an important reminder that experts need to do more than just show up. They have to focus on objective comparisons of protected expression and avoid relying on unprotected elements or on a subjective “feel” of the works, which remains the province of the jury.

The case may also serve as a cautionary tale when historical source material is used as the inspiration for an entertainment project. While no one has a monopoly on ideas or facts, and the Supreme Court has squarely rejected the “sweat of the brow” theory of copyright protection, the reality is that nonfiction works are often the subject of option/purchase agreements.

There are several reasons for this. The most gifted non-fiction writers are able to express, arrange and articulate historical facts in a highly creative manner, and acquiring rights in these works allows producers to tap into such narratives. Rights acquisitions also serve as an insurance policy of sorts, offering peace of mind and legal protection against claims of infringement that may be costly to defend, regardless of their merit. But as the Yonay case shows, producers should be aware that paying once could land you in the danger zone if you don’t pay again, whether warranted or not.

As always, I’d love to know what you think. Hit me up in the comments below or on your favorite social media app @copyrightlately. In the meantime, here’s a copy of the court’s ruling:

View Fullscreen

2 comments

Aaron, thanks as always for the cogent analysis of the Top Gun case. This case is an example of the old adage that success has many parents! Thus a hit movie is bound to attract copyright claims from one party or another, often more than one. When I was at WB, I sometimes joked that the multiple “alleged parents” of a hit movie should be required to duke it out among each other first, with the winner getting the chance to sue the studio! While I understand the 9th Circuit’s instinct to reign in pleading-stage district court dismissals of plagiarism claims, I hope all the judges recognize the need for them at times. Defending lawsuits through discovery and summary judgement, and with expert witnesses, can be very expensive. With that in mind, potential plaintiffs can be tempted to “take a swing” at film producers–especially if plaintiffs’ legal fees are contingent–in the hope of an early settlement. That in turn can lead to blatantly unfounded claims. Moreover, a battle of the experts is often a standoff, leaving the court pretty much where it started. If the claim is not obviously unfounded, experts may help. In this Top Gun case, I suppose it did help the court to hear from an actual former pilot. But did he add much to the 1983 article?

Thanks Jeremy. I agree that the Ninth Circuit may be staking too much faith on expert witnesses, many of whom may be little more than hired guns that don’t add much real value. The court should also consider the enormous legal costs involved in allowing cases with dubious merit to proceed to discovery. But as I’ve noted before, the single biggest problem in my view is a lack of any definitive guidance from the Ninth Circuit (i.e., not a single published opinion) that would clarify the standards for pleading stage dismissals.