Amazon and MGM Studios raise the stakes in a copyright termination fight over the Road House reboot, claiming that writer Lance Hill’s use of a loan-out corporation prevents him from recapturing the copyright in the original screenplay.

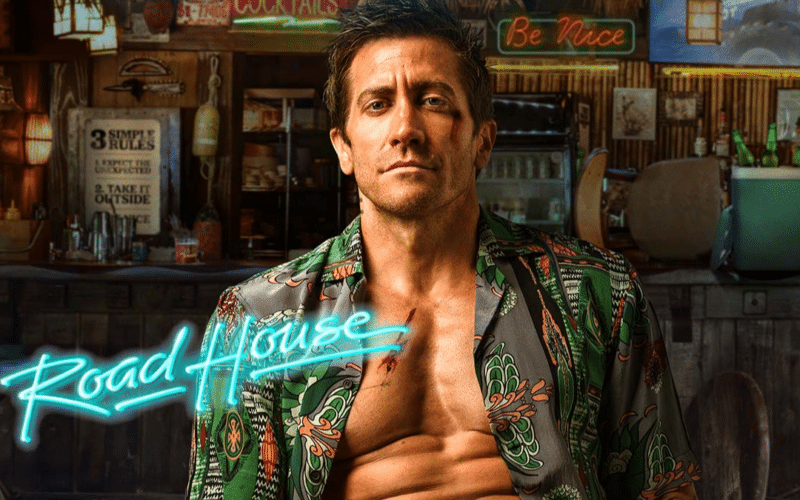

MGM Studios and its parent company, Amazon Studios, are punching back against a copyright infringement lawsuit filed by R. Lance Hill, screenwriter of the 1989 cult classic Road House. If you haven’t seen this Patrick Swayze trash action masterpiece, I’m assuming your parents didn’t have basic cable, where the movie was shown more often than Taylor Swift at a Chiefs game. Hill’s complaint, filed in February (read here), claims that the studio moved forward with a 2024 reboot starring Jake Gyllenhaal’s abs despite receiving a termination notice purporting to recapture the copyright in Hill’s original screenplay.

Hill v. Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer Studios

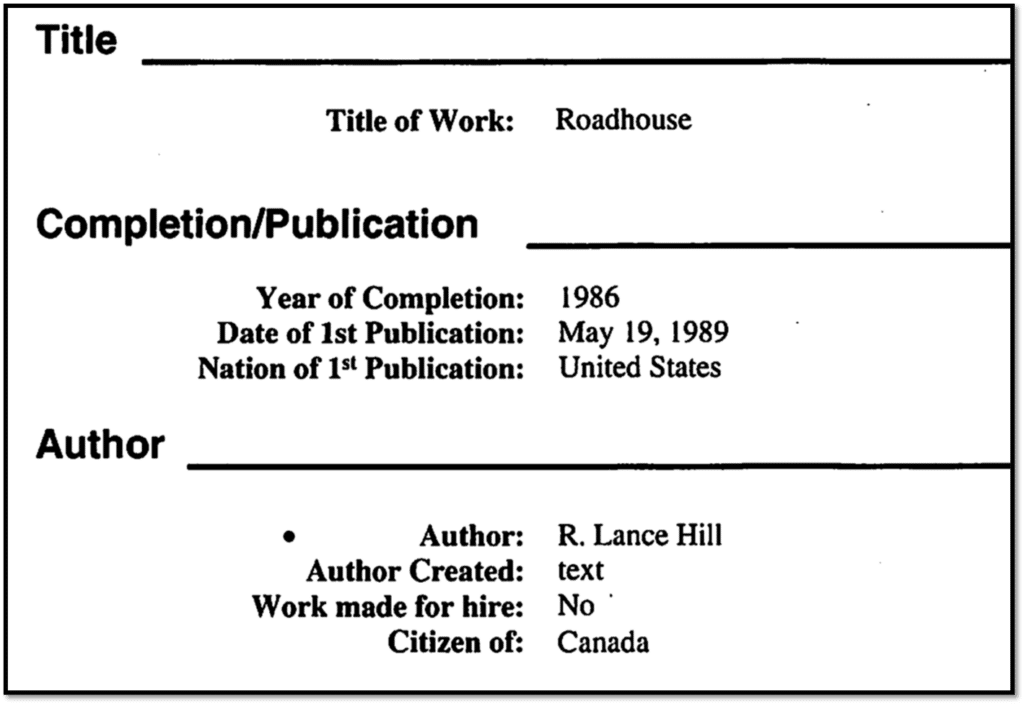

Hill’s termination notice relies on a provision of the Copyright Act that gives authors the right to terminate post-1978 copyright assignments and licenses as early as 35 years after they were originally made. Following termination, the author will reacquire the previously assigned rights. But there’s an important exception: works made for hire aren’t subject to termination. (While Hill’s complaint also generated headlines for its allegations that Amazon used AI to finish the film, those allegations are largely irrelevant to the copyright claims at issue.)

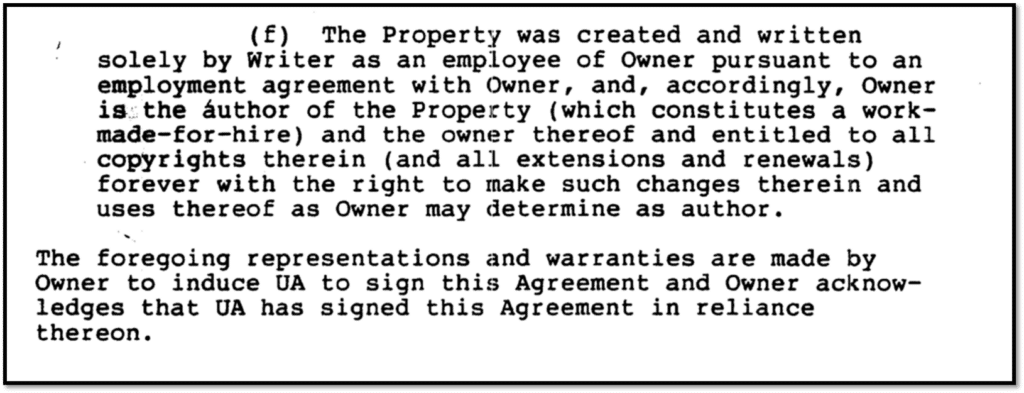

In its answer and counterclaim filed late Friday (read here), Amazon and Co. contend that Hill’s termination notice is invalid. They rely on an agreement in which Hill expressly represented that he wrote his 1986 screenplay Roadhouse as an employee of his loan-out company, Lady Amos Literary Works, Ltd., and that the screenplay constitutes a work for hire, making it ineligible for termination.

Amazon is also going on offense, asserting in its counterclaim that Hill and his attorney, Marc Toberoff, obtained a 2024 copyright registration in the original screenplay by fraudulently claiming to the U.S. Copyright Office that Hill was the screenplay’s “author.” Amazon says these representations are directly refuted by Hill’s acknowledgment 38 years earlier that Lady Amos was the legal author of the screenplay.

Copyright Termination and Loan-Out Corporations

I’ve written a lot about the interplay between loan-out corporations and statutory termination under the Copyright Act, most recently in connection with a June 2023 lawsuit filed by Columbia Pictures against the writers of a story on which the Bad Boys film franchise was based. That case is still pending, but only barely, as the parties have reached an agreement in principle on the key terms of a settlement and are currently in the process of drafting a settlement agreement.

While the Hill-MGM dispute may also eventually settle (most termination cases do), the litigation puts Hill in a tough position in the meantime. Attempting to recapture rights in his Roadhouse screenplay essentially requires him to admit that his previous representations and warranties at the time the screenplay was written were false.

In an effort to explain the seemingly inconsistent positions, Hill’s complaint discounts the work-for-hire language in the 1986 agreement as a “conclusory form recitation” insisted upon by MGM’s predecessor, United Artists, and claims that his loan-out “merely served as Hill’s alter ego for doing business.” Hill contends that he had “no actual employment relationship with Lady Amos,” and “did not receive any customary employment benefits” from the company “such as healthcare, a pension, unemployment insurance, or workers’ compensation.”

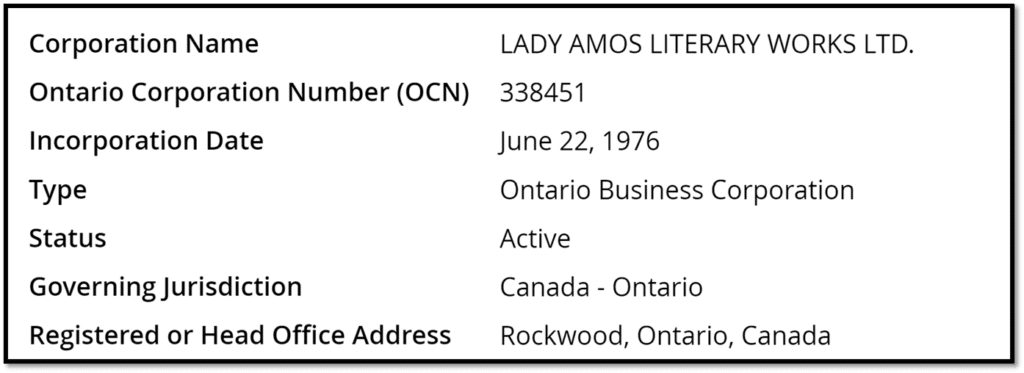

But if Hill didn’t receive any benefits from his Lady Amos loan-out, it raises the question of why he formed it in the first place. While the complaint seeks to portray Lady Amos as a fictitious entity that United Artists forced Hill to use, an Ontario, Canada business records search reveals that the company was formed in 1976—a decade before its 1986 assignment—and that it’s still in good standing nearly 50 years after incorporation.

The fact is that nearly all loan-out companies are wholly owned by the writers, actors, or producers they “employ,” existing solely to lend out the services of their artist owners. It’s a legal fiction, albeit one that affords a host of valuable perks—limited personal liability and asset protection, lower corporate tax rates, the ability to take business deductions unavailable to individuals, as well as the opportunity to direct earnings into profit-sharing plans that shield that money from taxes—none of which Hill’s complaint suggests he’s renounced.

As you might expect, the IRS isn’t a big fan of loan-outs. If the taxing authorities suspect that a corporation is a sham set up solely to avoid taxes, they may disregard the corporate entity, which can result in a reallocation of income, taxes at the higher personal rate, and potentially years of fees and penalties. Taking the benefits may mean also accepting the burdens. As one federal judge cautioned when faced with a similar case involving musician John Waite, “people cannot use a corporate structure for some purposes—e.g. taking advantage of tax benefits—and then disavow it for others.”

The Bottom Line

Loan-out corporations are commonplace in the entertainment industry. As music lawyer Don Passman once quipped, “Everybody on the block has one.” But despite their ubiquity, the question of whether assignments by loan-outs may be terminated is largely untested in court. While Toberoff no doubt wants to make law in this area, the Road House litigation puts his client in the rather unenviable position of having to explain to a federal judge that he didn’t really write his screenplay as an employee of Lady Amos and that the company was merely used to take advantage of favorable tax treatment and other benefits afforded to loan-out corporations.

It’s a risky gamble with potential implications extending beyond a dispute over the Road House copyright, and if the judge suspects that Hill’s trying to have his cake and eat it too, he may show the patience of a bouncer at last call.

I’ll keep you posted on the outcome of the latest copyright termination brawl. In the meantime, let me know your thoughts in the comments below or @copyrightlately on social.

View Fullscreen