The Case Against Roy Lichtenstein

Roy Lichtenstein is one of the most famous modern artists from the United States. There is no doubt that his comic book style made him one of the most well-known artists of the last century.

However, over the past few weeks and months, the talk around Lichtenstein been more about his appropriation of the work from comic artists and less about his impact on the art world.

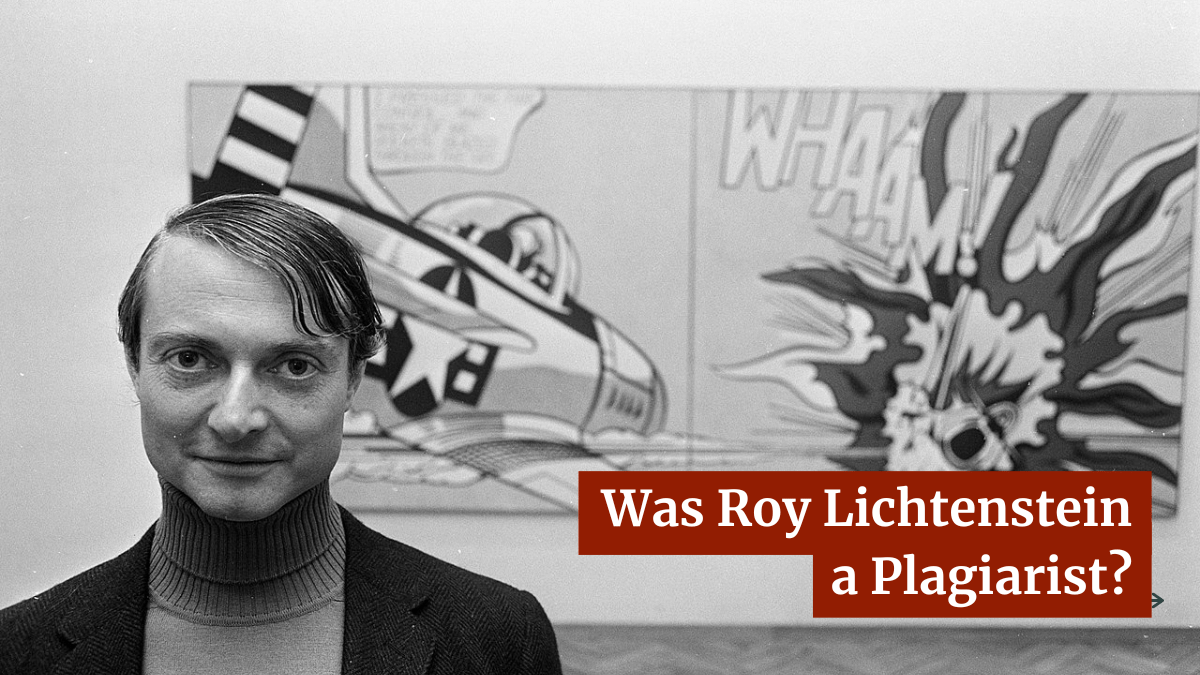

The reason for that is the release of a new documentary entitled Whaam! Blam! Roy Lichtenstein and the Art of Appropriation. Though released in November 2022, the documentary has been getting a great deal of media attention in the recent weeks, including The Guardian, CBR, Artnet News and more.

Though I’ve long been familiar with the allegations against Lichtenstein, I was curious to see if the documentary provided any new information or at least new arguments in favor or against the artist.

But, while there wasn’t that much new information to be found, the documentary did a fantastic job of humanizing the issue, making me think about both sides of the debate and reach some new realizations.

So, I’m going to first review the documentary itself and then look at some of the points made in it and offer my thoughts on them.

Recapping Whaam! Blam! Roy Lichtenstein and the Art of Appropriation

Roy Lichtenstein rose to prominence in the early-to-mid 1960s as part of the pop art and appropriation art movement that was spearheaded by Andy Warhol. Though he did a variety of styles over his career, by far his best known for his comic-style works. This includes works such as Wham!, Drowning Girl and In the Car.

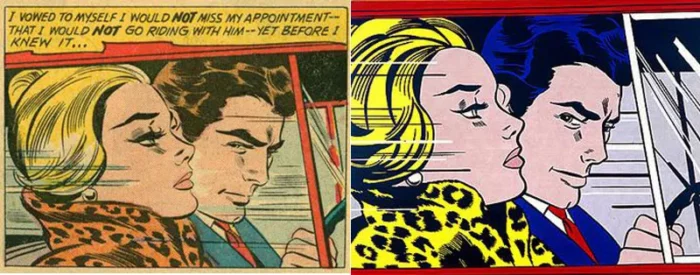

The controversy around Lichtenstein comes from the fact that many of his works, including some of his most famous, were reproductions of panels from comic books and comic strips. However, the sources of those works were never cited.

This brings us to the documentary, which relies heavily on the work of Lichtenstein historian David Barsalou, who has spent decades trying to track down the source images used. He has been posting them on his page, Deconstructing Roy Lichtenstein, where he claims to have found around 95% of the source images used.

In addition to Barsalou, the filmmakers also speak with two comic artists who had their work “appropriated” by Lichtenstein, Hy Eisman and Russ Heath. Both are artists who, despite having long careers in comic art, are living humble lives in their later years, even as Lichstenstein’s version of their works sell for millions of dollars.

Needless to say, they are not fans of Lichtenstein’s work. Eisman ends up uttering the film’s most iconic line, saying, “It’s called stealing,” when asked to describe Lichtenstein’s use of his work.

However, the filmmakers do an impressive job providing some counterbalance to those voices. They bring in a series of researchers and historians to provide a pro-Lichtenstein viewpoint as, these include an author who is an expert on Lichtenstein, a museum curator and art historians.

These voices talk about how Lichtenstein transformed and elevated the comic art that he used, and argued that he was an innovator in the space.

But the strangest pro-Lichtenstein voice was Bill Griffith, a comic artist and the creator of Zippy the Pinhead. He staunchly supported Lichtenstein’s work, saying that it was art. However, at the end, he did acknowledge that, if Lichtenstein had traced his work, he would consider that plagiarism.

The ending is also where the filmmakers tip their hand. Through most of the film, they carefully balanced pro and anti-Lichtenstein viewpoints. However, at the end, they focused fairly one-sidedly on the litigious nature of the Lichtenstein estate, including targeting a band that used a painting based on a Lichtenstein painting for an album cover and their actions against Barsalou.

Then, right after the clip of Griffith discussing how tracing would be plagiarism, they showed several clear examples of Lichtenstein having traced from the original work.

It was a very pointed end to a documentary that, largely, had been about balance between the viewpoints. Still, I wouldn’t call the film preachy or an attack piece on Lichtenstein. The goal was more about humanizing the discussion around Lichtenstein’s work and letting the audience make up its own mind.

Was Lichtenstein a Plagiarist?

To do a complete analysis of Lichtenstein’s work, we’d have to look at every painting and every source. The reason is that every work is different in how it approaches the source material. Some are pretty much traces of the original, while some make more significant changes.

That said, the evidence against Lichtenstein, in particular with some of his most famous works, is pretty damming.

Lichtenstein never attributed any of his sources and, without the work of Barsalou, we likely still wouldn’t know who many of the original artists are. Warhol and others may have appropriated famous items, but the audience knew who was pulling from or, at the very least, the subject wasn’t original. Many visiting Lichtenstein’s likely felt those were wholly original paintings done in a comic style.

To be clear, this came out during his lifetime. Even in the 1960s, some of the artists came forward. However, their complaints were largely ignored.

The reason for that is the same reason that many of Lichtenstein’s supporters today believe that he isn’t a plagiarist. They claim that he “elevated” or “transformed” the works.

However, that argument doesn’t hinge on anything in the paintings themselves. The argument hinges upon the idea that Lichtenstein was taking “low art” and transforming it into “high art” by enlarging it and hanging it on a gallery wall.

In Lichtenstein’s time, it was definitely seen that way. Comic artists were people making cheap, disposable works that were not seen as “art” by either galleries or by the public.

But that sentiment has changed drastically since then. However, I disagree with one person’s assertion that this is because of Lichtenstein. Lichtenstein didn’t magically elevate comics to art, comics were still seen as being “for kids” well into the 1980s.

Comics pulled themselves out of that with books like Watchmen and series like Spawn and Sandman. By proving that comics could be a medium to tell serious stories, the medium was elevated and that prompted a reevaluation of the works that came before.

The arguments that Lichtenstein isn’t a plagiarist hinge almost completely around the idea that Lichtenstein is “high art”, deserving of being called art, and comic art isn’t. If you view comics as art and equally deserving to be called art, there’s no ducking the word “plagiarist”, at least when looking at many of his works.

To put it another way. If a musician did this to another musician’s song, we’d call it a cover and demand attribution. If a filmmaker did this to another filmmaker, it would be called a remake. If a filmmaker did this to an author, it would be called an adaptation.

The only way to view Lichtenstein’s work as transformative is if you view comic artists as unworthy or lesser than that of “real” artists.

This, clearly, is the view the art community still holds when it comes to Lichtenstein.

But What About Copyright?

The film also delved briefly into the copyright implications and brought in Marc Greenberg, an expert in comic art law, to discuss it.

To that end, there were two main threads in the copyright conversation.

- If the artists wanted to sue, they couldn’t have. Most of them were employees of the comic company or had exploitative contracts that granted the company copyright in the work. Either way, the companies opted not to sue, and that was their choice.

- Even if they could sue, they likely would not have won due to fair use.

Both statements are accurate. Artists, as employees or as contractors who had signed over their rights, had no rights to the works they created. Even if they did sue, they likely would have had an uphill battle.

Though fair use wouldn’t be codified into law until The Copyright Act of 1976, it was widely observed by the courts before then through a series of court decisions leading up to that point.

Given the clout that Lichtenstein had and how comic artists were viewed at the time, it would have been a struggle.

We’ve even seen this recently. In 2013, Richard Prince won a key legal victory over his use of photographer Patrick Cariou’s work in his “appropriation art”.

However, even as the documentary was being filmed, the legal tides were possibly shifting. In 2021, the Second Circuit Court of Appeals, the same that ruled on the Richard Prince case, handed down a significant ruling against the estate of Lichtenstein contemporary Andy Warhol.

In that ruling, the court said that fair use is not about how much transformation took place but whether the new work added some, “new expression, meaning, or message.”

Lichtenstein’s work didn’t really do that. The expression, meaning and message within the paintings themselves were the same. Any transformation was, as we discussed, from the elevation of “low art” to “high art”.

What Lichtenstein did to the original artists is much more similar to Warhol’s paintings than it is to what Prince did.

However, the Second Circuit will not be the final word in this matter. That case was heard at the Supreme Court in October and a ruling is expected soon. It will likely be one of the most important fair use decisions in history, making it something to watch very closely.

Bottom Line

In the end, what I walked away with from the documentary was a feeling of how cruel Lichtenstein and the art world has been to the original artists.

Lichtenstein easily could have credited his original authors. Galleries could have, and still could, display the source panels next to Lichtenstein’s paintings. Lichtenstein still would have been famous for “elevating” comic art, but those artists might have become a bit more famous, made a bit more money and had easier lives.

Instead, he lifted from them, in some cases tracing their work, without even giving the pittance of attribution. It shows just how much disrespect there was for comic artists at the time.

This was encapsulated perfectly by a photograph shown in the documentary featuring Lichtenstein showing off one of his paintings while, on the ground at his feet, was the cut up comic pages he had used to make it.

There’s not much doubt that he would be seen as a plagiarist if he tried this today. However, he was also likely a plagiarist by the standards of his time. It’s just that few knew and those that did know didn’t care. To them, he was just pulling from comic books, it wasn’t like he was copying real art.

For anyone who’s upset by that conclusion, I offer one consolation. One of the points of appropriation art is to poke at issues around what is original? What is a plagiarism? And what is citation?

The very nature of the genre is to cause people to ask those questions. The fact we’re still talking about those issues 60 years later says something about Lichtenstein as an artist.

But it doesn’t mean that he isn’t also a plagiarist. As we’ve seen time and again, one can easily be both.

Want to Reuse or Republish this Content?

If you want to feature this article in your site, classroom or elsewhere, just let us know! We usually grant permission within 24 hours.