We’re pleased to bring to you a guest post by Pragya Jain. Pragya is a 5th year B.A. L.L.B.(Hons.) student at Amity University (School of Law), Kolkata. Her previous guest post on the blog can be viewed here.

Harpic v. Domex Advertisement: Product Disparagement or Nominative Fair Use?

Pragya Jain

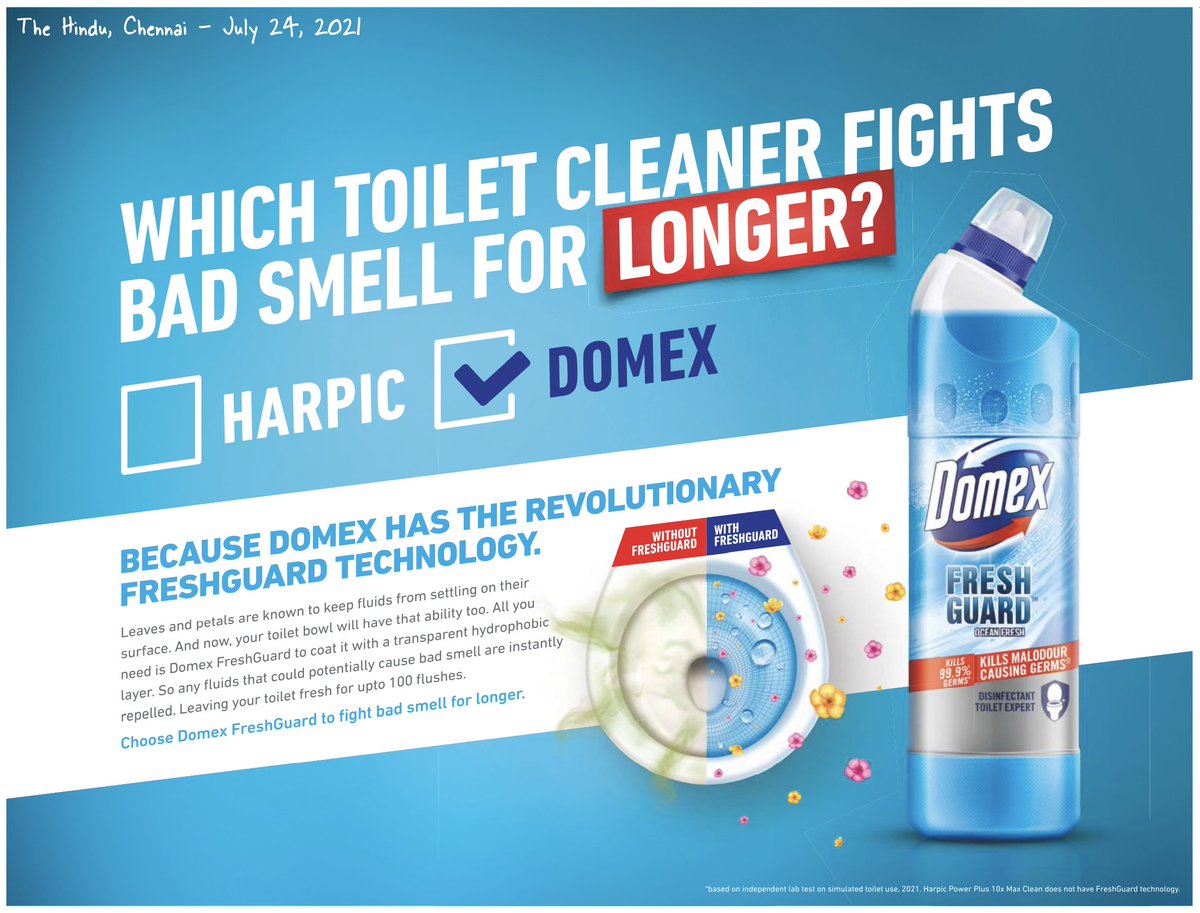

Advertising is an important factor in deciding a product’s future success. It is common knowledge that it is the most effective and proven method of attracting new customers in the industry. Due to the large number of products available to consumers, advertisers frequently compare their products to those of competitors. In common parlance, comparative advertisement means advertisement of a particular product, or service by comparing it against a competitor’s product for the purpose of showing why one’s product is superior. Recently, Domex, a Hindustan Unilever brand, has launched a new ad campaign across print, digital and other media, at least some of which explicitly compares itself to Reckitt Benckiser’s toilet cleaner brand ‘Harpic’. One of the ads in the campaign – a commercial available on YouTube – begins in a supermarket with a woman picking up a bottle of Harpic when her son inquires if the brand can also kill toilet odour. At this point, television actresses Divyanka Tripathi (Hindi version) and Revathy (Tamil version) explain that Domex uses fresh guard technology to combat toilet odour, something that the other brand can’t.

This is not the first time that these companies have engaged in comparative advertising for the same products as discussed in a previous post. Reckitt Benckiser has already approached the Delhi High Court and an interim injunction has been granted against one of the print advertisements, as has been discussed further in the conclusion. The case is scheduled for further hearing this week.

In this post, I offer my independent analysis of the law in relation to comparative advertising and nominative fair use and apply it against the specific YouTube commercial mentioned above.

Legal Position on Comparative Advertisement

The advertising of one’s own goods is not prohibited. In was observed by the Hon’ble Supreme Court in the case of Tata Press Limited v. Mahanagar Telephone Nigam Limited & Ors. that under Article 19(1)(a) of the Constitution, which deals with freedom of speech and expression, the right to “commercial speech” is recognised. Nevertheless, it goes without saying that this right is not unlimited in nature and should not be abused.

Puffery and denigration are the two main types of comparative advertising. There is a thin line separating puffery and disparagement. Making exaggerated claims about one’s own goods and comparing them against the other available products in the market in order to persuade the public to buy the former is puffery. When the same promise is made by smearing the image of a clearly identifiable competitor product, it goes beyond puffery and becomes denigration of the product. In the case of Colgate Pamolive (India) Ltd. v. Anchor Health and Beauty Care Pvt. Ltd., the Delhi High Court observed that disparagement happens when an advertisement castigates or berates the products of others in order to increase the popularity of the product it represents among the general public.

Section 29(8) of the Trade Marks Act, 1999 (‘Act’) clearly states that an advertisement of a particular mark/brand amounts to infringement of the trademark if it takes unfair advantage of another trademark, or is detrimental to the very distinct character of the other trademark, and is also against the trade mark’s reputation.

In the case of PepsiCo. Inc. v. Hindustan Coca Cola Ltd., the Delhi High Court outlined the considerations when determining disparagement:

- Commercial intent of the advertisers in respect of what they are trying to achieve in order to promote their goods;

- The most crucial component is the nature of the commercial. It is disparaging if the method is ridiculing and criticising, but it is not actionable if the manner is just to demonstrate that one’s product is superior without demeaning the product of others;

- The commercial’s plot and the message it is attempting to convey.

When we apply the above tests, it is clear that the advertisement of Hindustan Unilever for its product Domex is disparaging the image of its competitor product, Harpic of Reckitt Benckiser. It does so by taking a direct dig at Harpic as a toilet cleaner and questioning its utility in containing malodour and disinfecting the toilet over a large period. The next question is whether Hindustan Unilever can defend themselves on the grounds of nominative fair use.

Is the Defence of Nominative Fair Use Available to Hindustan Unilever?

Section 30(1) of the Act justifies comparative advertising, authorising the use of a registered trademark for the purpose of identifying goods or services of the competitor but such use must only be done in accordance with the honest and fair trade practices without any mala fide intent in order to take advantage of a competitor’s goodwill.

Under Section 30(2)(d) of the Act, nominative fair use by a third party does not qualify as trademark infringement if neither the purpose nor the effect of the use of the mark causes any confusion as to trade origin. In its most basic form, nominative fair use of a trademark is a legal doctrine that can be used as a defence in some types of trademark infringement cases, such as when a registered brand is used by someone else to allude to the mark owner’s goods or services. This use is deemed nominative because it “names” the genuine owner of the mark.

In Consim Info Pvt. Ltd v. Google India Pvt. Ltd., the Madras High Court held that any unauthorised use of trademark must meet three tests to be considered a ‘nominative fair use,’ namely,

- the product or service in question must be difficult to identify without the use of the trademark;

- only as much of the mark or marks as is reasonably necessary to identify the product or service should be engaged in; and

- the user must do nothing that suggests sponsorship or endorsement by the trademark owner when using the mark.

In the abovementioned advertisement, there is definitely no suggestion of sponsorship or endorsement. However, it isn’t difficult to identify the product, i.e. Domex, without referring to Harpic. It can be further contended that the purpose of the advertisement to present the Domex as an odour remover could have been achieved without mentioning or referring to the Harpic trademark. Thus, the defence of nominative fair use is not available for Hindustan Unilever.

However, in the case of Havells v. Amritanshu, the Delhi high court ruled that an advertisement, for it to qualify as nominative fair use, may highlight just a specific quality of the product that distinguishes it from that of a competitor as long as the comparison is accurate and true. Thus, Hindustan Unilever can take the defence of honest and true representation of facts. Nevertheless, this is also subjected to the provision of fair trade practice under section 30(1).

Conclusion

Coming back to the current dispute, the Delhi High Court on 30th July granted an interim injunction against one of the print advertisements, in which Harpic was explicitly identified (the one in the image along with this post), till such time all references to Harpic are removed. As regards the other ads in the ad campaign, the Court held that a conclusion can be arrived at only after a detailed examination of the reply that may be filed by the Defendant.

In in its analysis, the Court referred to two important precedents – Dabur India v. Colortek Meghalaya Pvt. Ltd. and Colgate and Anr. v. Hindustan Unilever Ltd. – in which it was observed that although comparative advertisements are a form of commercial speech under Article 19(1)(a) of the Indian Constitution, if it takes a negative form to defame a brand or denigrate its value, then it amounts to disparagement.

As we await the final outcome in this ongoing dispute, this much can be said: while comparative advertising itself is not illegal, advertisers should, however, guarantee that the basis for comparison is fair and accurate, and not chosen to give themselves an unfair advantage. Other marketers must not be unfairly disparaged or disregarded in such comparable commercials. After all, the Supreme Court in Tata Press v. Mahanagar Telephone Nigam Ltd. had observed that ads not only benefit manufacturers, but also allow for a free flow of information in a free market economy, achieving the larger purpose of public awareness. In the present instance, the advertisement could have reflected upon the special characteristic of Domex, i.e., it can improve toilet odour without referring to the brand name of the opponent.