Recently, there has been an increase in the number of advertisements on social media for perfumes that offer the same fragrance as a luxury one at a reasonably affordable rate. If you have come across such ads and have wondered whether such use of a mark infringes the mark of the luxury brand, then you are not alone. We are pleased to bring you a guest post by our former SpicyIP Intern Ishant Jain, who shares his opinion on this question. Ishant is an LLM candidate at the WBNUJS, Kolkata. He comes from Firozabad, UP, and is looking forward to building his career in Intellectual Property Rights.

Smells like Luxury, Does it cost a Trademark Battle?

Ishant Jain

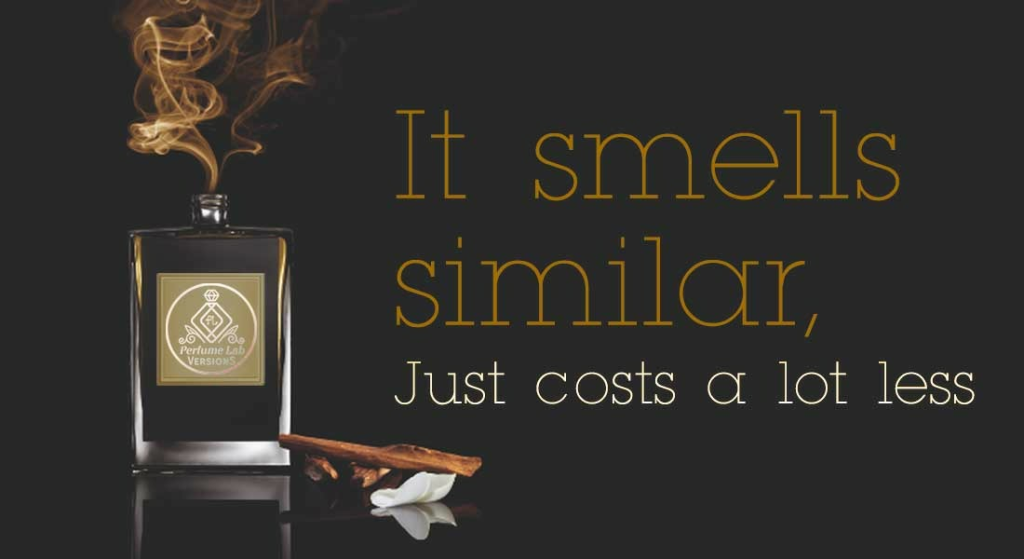

The rise of comparative advertising in the perfume industry (for instance see here and here) sparks debate on issues of potential trademark infringement and disparagement. In this post, we will explore potential claims raised against advertisements by outlets offering cheaper alternatives to luxury perfumes, often associating their products with the original brand. Also, the websites give a disclaimer that the perfume is not associated with the luxurious brand or offers that quality but only offers an exact smell (see here and here). I argue that such usage does not infringe the trademark of the luxury brand or constitute free-riding on the goodwill of the luxury brand.

Trademark Infringement

The advertiser compares two perfumes showing them side to side in the ad video and claims to create a version of the luxury perfume. The video attempts to create the impression of smell being identical (smell not being the subject of TM protection in India). The comparison is limited to the fragrance, however, the cheaper alternative is, not for once, passed off as a product of the luxury brand.

It is notable that in some advertisements, there are distorted names of the luxury brands (here, here, and here) used to indicate their product name. It clearly could lead them to a trademark dispute as use of a mark similar to a registered mark for similar goods are generally deemed as infringement under Section 29(2)(b); however, as discussed below, alongside similarity of trademark and goods, other elements are also to be satisfied.

Taking a step back, trademark infringement under Section 29(2)(b) of the Act requires proving the following:

1. Unauthorized Use in the Course of Trade

The two-fold condition asks, first, to prove “unathorised use as a trademark” and second, such “use” ought to be in the course of trade.

Importing this into our analysis, there seems to be no authorization to use the trademark of the luxury brand. However, the mark has merely been used in the course of trade, in a comparative or nominative sense. This is evident from looking at the packaging and branding of the perfume whereby the perfumes are sold by their version id. It has not been used, specifically, as a source identifier or as a trademark for it to comprise use that is relevant to Section 29(2)(b).

Notably, however, Section 29(8) provides use of a mark for an advertising purpose to also be infringing (often termed as disparaging), if it is unfairly benefitting or tarnishing or blurring the mark. We will explore the relevance of this further ahead in this post.

2. Likelihood of Confusion to the Public or Likelihood of Association with the Registered Trademark

I. Likelihood of Confusion to the Public

Assuming you recognize the scent of luxury perfume and encounter a similar fragrance at a party, it may evoke the image of the luxury brand in your mind. This offers consumers a tempting option to purchase an affordable perfume that smells similar to a luxury brand that is already well known. and still exude a luxurious aura at events. This product introduces competition in the market and expands the availability of cheaper alternatives. While this argument appears compelling in terms of product usage, trademark law places greater emphasis on the “likelihood of confusion” at the time of purchase.

Let’s explore how confusion may arise, if at all.

The luxury brand may claim that the advertiser jeopardizes the origin of the perfume by naming them as a version of their perfume and thereby causing a likelihood of confusion among the buyers.

Coming to the first impression, as held in Cadila Healthcare Limited vs Cadila Pharmaceuticals Limited, it clearly specifies itself as a ‘version’ of the Luxury perfume and not a counterfeit product passing off it as a branded perfume. The packaging nowhere resembles or is that of the branded perfume. Further, in the advertisements, the advertiser makes it very clear in their claim that they are taking inspiration from the branded perfume and recreating the fragrance. So, the first impression that comes to a consumer’s mind would be that they copied the formula of the perfume and thereby sold it and not that the same luxury brand is selling the perfume.

Relying on the observation of Parker, J. in Re Pianotist Case, Amritdhara Pharmacy Vs. Satya Deo, noted that in considering the matter, “all the case circumstances must be considered”. The advertisement itself indicates the perfume to be an inspired version of the luxury perfume and a consumer of Average Intelligence and Imperfect Recollection would also be able to understand that the “version” of a luxury perfume is not the luxury perfume itself and if the packaging is also similar (which smartly enough is not), the perfume wittily does not fail to call itself to be not associated with the brand. Even if the experiences of the two perfumes are the same, there should be no doubt that the present perfume is of a different brand. There might be a situation where a person buys a perfume just by examining the smell of the perfume and expect it to be the luxurious one, something notable here is that the websites clearly indicate that the perfume is meant to smell the same and never claim to be of the same quality (smell duration, perfume expiry date, etc), further, they also give an indication to use the name of the brand for reference purpose only (as done here) as permitted in Section 30(2)(a).

In the authors’ opinion, it does not directly affect the function of the trademark as a source identifier but it might affect the quality expectation of the consumer (had they been confused) which comes with the luxury brand and the advertising function of the trademark. But it simply does not confuse the public regarding the origin of the perfume at all.

II. Likelihood of Association with the Registered Trademark

One might question the comparison between two products as a practise of associating the two products. For example: When I compare two pens, I might say one is darker than the other or it has a better grip than the other one. But when I say “it is a wood version of the pen”, I am claiming it to be associated with or related to the previous pen. However, it might have been associated with the luxury brand had there been no clear indication of it being a version created by another manufacturer, in a different (local majorly) packaging, with local or no trademark.

Disparagement: Unfair Advantage and Free Riding, How?

Colgate Palmolive Company & Anr. v. Hindustan Unilever Ltd, discusses that disparagement refers to negatively comparing products in an advertisement, denigrating the competitor’s product or services, and harming their goodwill. However, using another brand name or trademark alone does not amount to disparagement. Section 29 (8)(a) of the Trademarks Act addresses disparagement through unfair advantage as:

“A registered trade mark is infringed by any advertising of that trade mark if such advertising— (a) takes unfair advantage of and is contrary to honest practices in industrial or commercial matters;…”

Let’s look at how the present situation constitutes disparagement if it does under clause (a).

One would argue that the act of calling its perfume to be a version of luxury perfume indicates the intention (as discussed in Pepsi Co. Inc. v. Hindustan Coca-Cola Ltd.) of the advertiser to unfairly utilize the goodwill created by the luxury perfume. The advertiser refers to the perfume of the luxury brand to sell his own perfume and divert the consumers. The source of increasing sales of the advertiser’s perfume is the goodwill of the luxury brand and the advantage of the goodwill. Thereby they commit free-riding or latching on to goodwill established by the luxury brand. There is no doubt that the advertiser is getting an advantage of the goodwill of the luxury perfume but is the advantage unfair?

One may rely on the judgment of L’oreal v Bellure for unfair advantage and also on the order passed in Akash Aggarwal vs Flipkart Internet Private Ltd. for “‘latching on’ to another’s name/mark and product listings is `riding piggyback’ as is known in the traditional passing-off sense and thereby amounts to taking unfair advantage of the goodwill that resides in the Plaintiff’s mark and business” In this scenario, the advertiser is inspired by a luxury brand but doesn’t use the trademark or photograph for source identification. Goodwill is in the mark, not the product. An unfair advantage can only be taken through the mark, not the product. The order doesn’t apply as the advertiser doesn’t use the trademark or photograph without a disclaimer and not in the manner used in Flipkart’s case.

One might argue that a version could be created without announcing to the world that it is a version of the luxury perfume and so is done solely to gain an advantage of their goodwill. It is not reasonable if it is legal to create a version of the fragrance and announcing the same is not. However, without announcing it, how would potential buyers know about the similarity of the fragrances? It only mentions luxury perfume to identify that its perfume is an alternative to luxury perfume. It could be claimed to be unfair based on diversion of consumers but the advertiser provides additional options to the consumer in the market and increases healthy competition by referencing, which is one of the purposes of Trademark Law in India and not unfair anyhow. The advertiser doesn’t utilize the source identification facility of the luxury trademark for the commercial/sale purpose or to confuse the public but for comparison, which would have been if they claimed their product to be of the luxury brand, and as noted earlier, there is always a clear indication of non-association, to make it an unfair advantage issue.

In conclusion, no harm or confusion arises for the luxury brand or the public, and competitors benefit from the investment made in establishing the luxury brand and its goodwill and get an advantage but not unfair. Such advertisements cannot be considered infringing under section 29(2)(b) as they don’t confuse the general public. By using non-association indications like labels or referring to themselves as inspirational products or versions, even after the advantage, they avoid liability under section 29(8). Nonetheless, it is hoped that future clarity will determine the fairness of this advantage. In the meantime, feel free to enjoy purchasing a luxury fragrance.

The author would like to thank Akshat Agrawal for his input.