“Despite the valid, socially conscious reasons fueling the growth of the upcycling movement, upcycling raises legal concerns and challenges regarding maintenance of brand reputation, especially for luxury brands.”

Upcycling, a recent fashion trend, poses issues and concerns for brand owners that are similar to counterfeiting but with some added complexity. As a result, upcycled products have prompted brand owners to take legal action to protect their brands and consequently their customers. Below, we (1) explain what upcycling is, (2) discuss potential legal issues arising from upcycled products, (3) summarize recent cases involving upcycled products, and (4) propose successful brand protection measures.

What Is Upcycling?

We are all increasingly aware of our footprint on Earth. With our growing environmental consciousness, we are moving towards more sustainable ways of living in all aspects of our lives. The fashion industry is no exception. Bain & Company reports that “about 15% of global fashion consumers are already highly concerned about sustainability and consistently make purchasing decisions to lower their impact.” Bain & Company further predicts “that percentage could increase to more than 50% in the coming years as more shoppers gravitate toward sustainable practices.” In line with that, offering a second life to pre?owned merchandise has gained tremendous momentum and garnered remarkable success.

Upcycling is the act of converting old or outdated resources into value?added goods. Upcycling promotes circular and sustainable fashion, as existing material remains in circulation instead of ending up in landfills. Upcycling has two components: (1) the original piece and (2) the modified subsequent piece with added value.

Upcycled pieces generally include buttons, zippers, fabric, leather, dust bags, and other components from designer merchandise reworked into jewelry pieces, accessories, and clothing items. For example, with some scissors and a sewing machine, one genuine Louis Vuitton bag can create at least several upcycled products:

According to Vogue magazine, upcycling was the biggest fashion trend of spring/summer 2021. As of June 2023, the hashtag #upcycle has over 6.2 million posts on Instagram alone, featuring diverse DIY upcycle artworks, garments, and furniture. Bain & Company forecasts that this trend’s momentum and success will only continue to grow and “resale could account for 20% of a luxury company’s revenue by 2030.”

Potential Issues Arising from Upcycled Products

Despite the valid, socially conscious reasons fueling the growth of the upcycling movement, upcycling raises legal concerns and challenges regarding maintenance of brand reputation, especially for luxury brands.

Post-sale confusion

Post-sale confusion can harm a brand owner. When products that appear to come from a trademark owner’s brand do not live up to the standards that consumers have come to expect of that brand, consumers may lose trust, thinking that brand’s quality has diminished.

Dilution of brand

For many higher-end consumers, part of the allure of luxury brands is a certain level of exclusivity. When the market is flooded with products that appear to come from the brand, however, this exclusive image can quickly be reduced to a fashion trend easily accessible by the general public, curtailing the appeal of the brand to higher-end consumers.

Diversion of sales

Lastly, upcycled products could impede sales by the trademark owner, as many of these products look very similar to originally purchased luxury goods.

Given the issues above, some trademark owners have been taking upcyclers to court in an attempt to preserve their rights and protect their brands.

Infringing Upcycled Products

Trademark infringement is the unauthorized use of a trademark or service mark on or in connection with goods and/or services in a manner that is likely to cause confusion, deception, or misconceptions about the source of the goods and/or services.

Upcycling involves changing the form and function of the original product. Because such alteration is done by embedding registered trademarks in upcycled products, it can cause confusion among consumers, prompting lawsuits by the original trademark owners.

The First Sale Doctrine of Trademark Law

Certain uses of trademarked goods however, are permitted by law without the trademark owner’s consent, including by virtue of the affirmative defense of first sale. Under the first sale doctrine, once a genuine, branded good is within the stream of commerce through a legitimate first sale, trademark protection is exhausted. Once such protection is exhausted, a subsequent sale of a genuine, branded good without the trademark owner’s consent does not violate trademark protection, except for sales that are misrepresented as authorized sales of the original trademark owner. Genuine goods are those goods that are manufactured and first sold with the authorization of the trademark owner, and without any modification.

The first sale doctrine places an obligation on resellers of trademarked goods to not sell the products in a way that would suggest to consumers that they are connected to the trademark owner. Thus, subsequent sales misrepresenting an affiliation or connection to the trademark owner act as a bar to applying the doctrine. In that way, a first sale defense turns on the same question underlying trademark infringement: whether consumers are likely to be confused.

If the first sale doctrine arguably applies to the issues at hand, the question then becomes whether there any exceptions to the doctrine. One exception is the material difference exception, where an alleged infringer sells the trademark owner’s goods that are materially different from the goods of that trademark owner. Unauthorized repackaging, reconstruction, and other modifications by the resellers of trademarked goods amount to material differences.

To summarize the first sale doctrine in the trademark context:

- Rule: After the first authorized sale of the trademarked goods, the trademark owner has no control over subsequent sales and the subsequent sales will not amount to trademark infringement.

- Exception: The first sale doctrine will not apply when products being resold are materially different from goods sold under the mark.

The First Sale Doctrine as Applied to Upcycling

Upcycled products present unique legal challenges. Because the original sale of a genuine, trademarked product that is eventually upcycled and resold tends to be authorized, the doctrine of first sale would appear to protect upcyclers. Recall, however, that an upcycled product is, by its nature, materially different than the original trademarked products, which is one of the exceptions to the doctrine’s rule. This has led to a series of lawsuits against upcyclers, especially in the fashion industry:

i. Louis Vuitton Malletier S.A.S. v. Sandra Ling Designs, Inc. No. 4:21-CV-00352

(S.D. Tex. Dec. 1, 2022)

Louis Vuitton sued Sandra Ling Designs and Sandra Ling, alleging trademark infringement for the sale of apparel, handbags, and accessories made from purportedly authentic pre-owned Louis Vuitton goods customized with stones, tassels, and beading. The court did not get an opportunity to rule on whether the defendants’ actions constituted counterfeiting because the defendants filed an offer of judgment and Louis Vuitton accepted that offer. Though the parties stipulated to no liability or damages, the defendants agreed to a permanent injunction and to pay $603,000. Photographs of representative examples of the allegedly infringing upcycled products at issue in this case appear below.

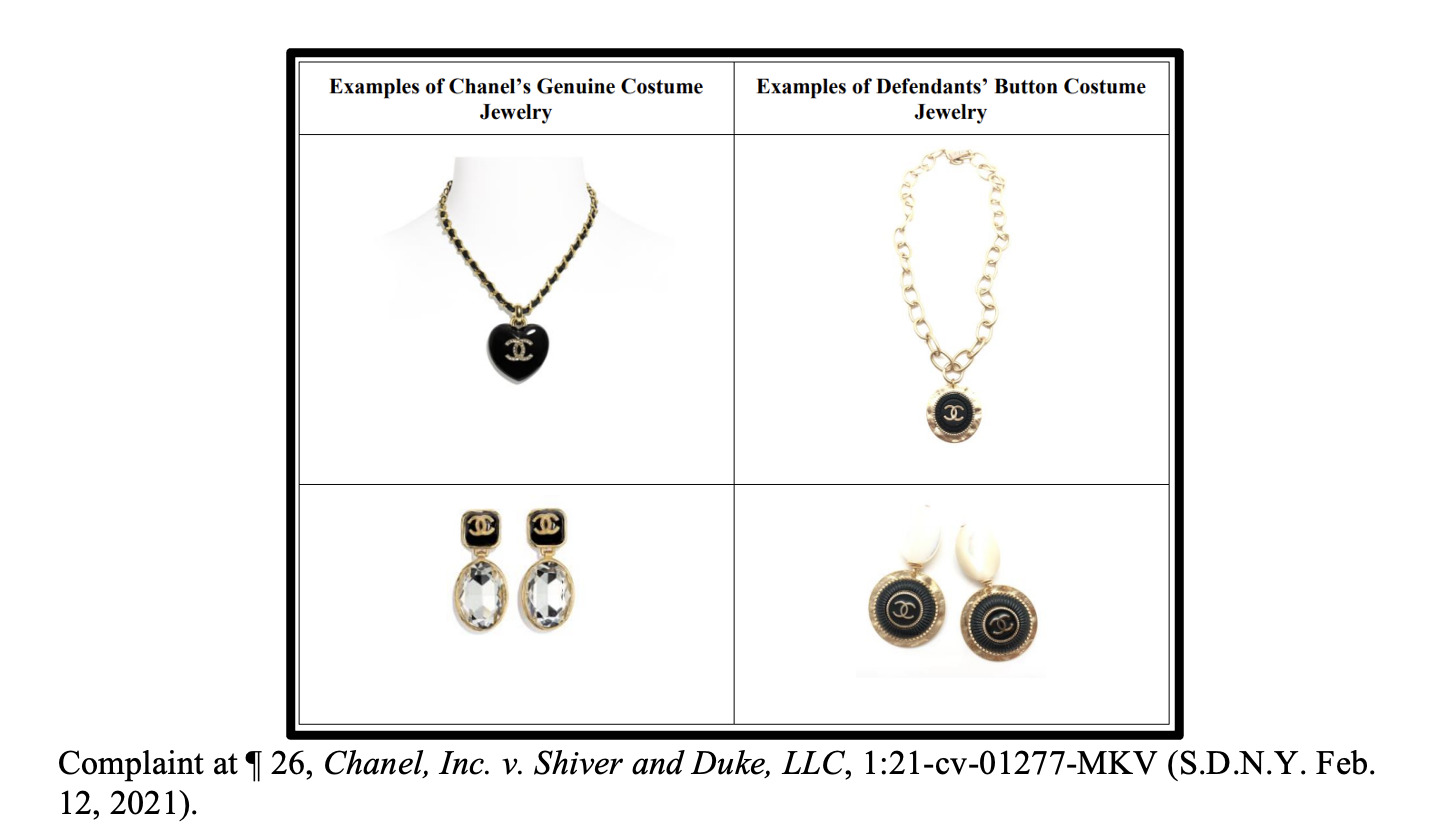

ii. Chanel, Inc. v. Shiver and Duke, LLC, No. 1:21-cv-01277-MKV (S.D.N.Y. Nov. 29, 2022)

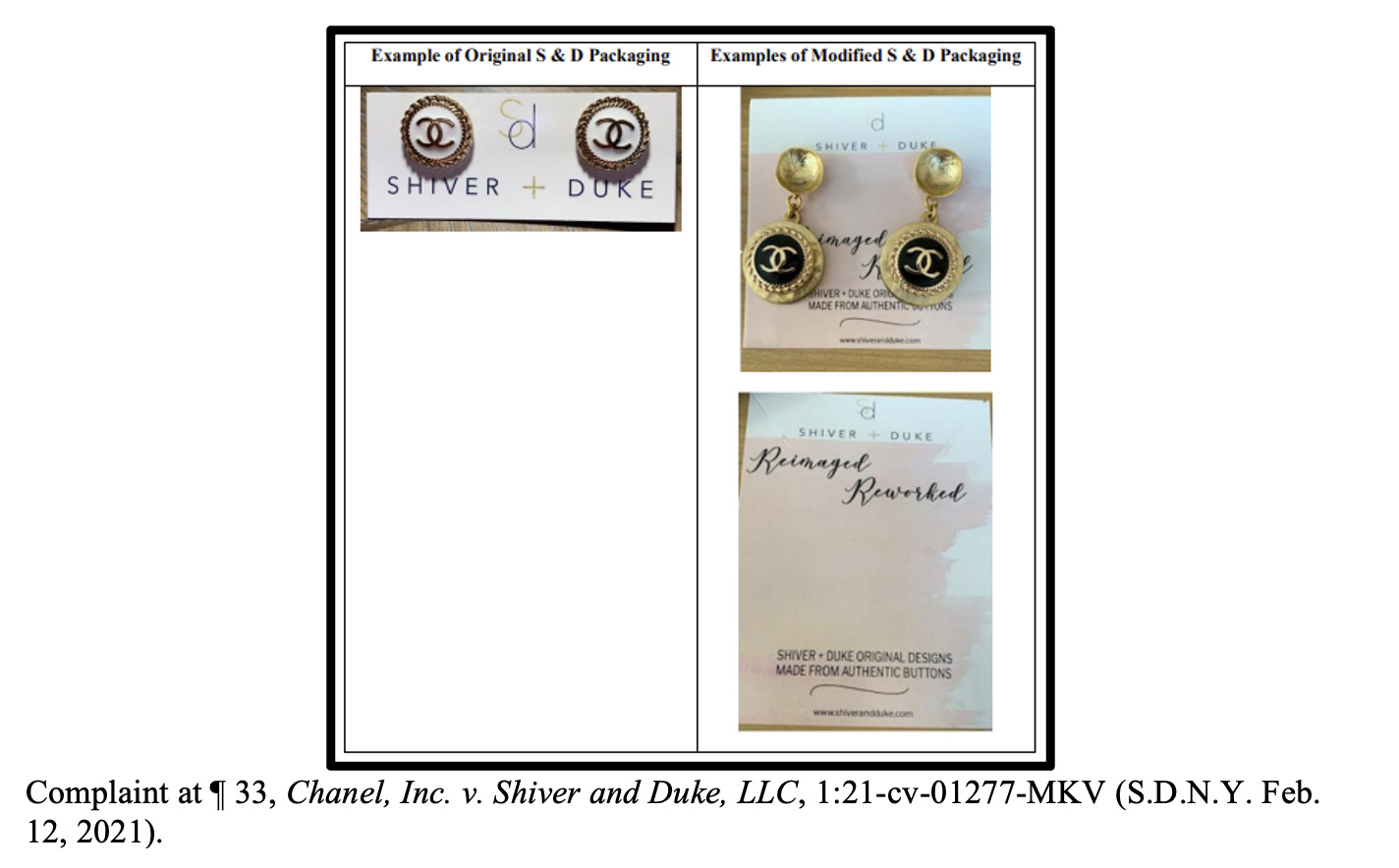

The Southern District of New York entered a stipulated judgment in favor of Chanel, permanently enjoining upcycling company Shiver + Duke from refashioning authentic Chanel buttons bearing the CC monogram and putting such buttons on chains, earrings, and bracelets. Chanel filed a complaint on February 12, 2021, for trademark infringement, unfair competition, and trademark dilution. The complaint alleged that “[t]he prominent mark and feature of the costume jewelry is Chanel’s CC Monogram. The commercial interest in the Defendants’ jewelry is based on the use of Chanel’s iconic trademark on the jewelry and the use of the CHANEL name to promote and market the jewelry.”

Before filing the lawsuit, Chanel sent a cease-and-desist letter. Rather than cease the use of the CC monogram, the defendants made minor changes to their products and packaging by adding the words “reimagined” and “reworked.” However, the packaging still did not state that the jewelry was not authorized or associated with Chanel. Shiver + Duke also added its “SD” markings on the backs of the Chanel-inspired jewelry and on their tags. In the complaint, Chanel alleged, “in the post-sale context, the mark most prominently displayed on Defendants’ jewelry belongs to and identifies Chanel as the source of Defendants’ products.” Defendants simply denied those allegations. Shortly after the court denied the Defendants’ motion to dismiss Chanel’s complaint for lack of personal jurisdiction or, in the alternative, to dismiss or transfer venue based on forum non conveniens, the parties settled. Photographs of representative examples of the allegedly infringing upcycled products at issue in this case appear below.

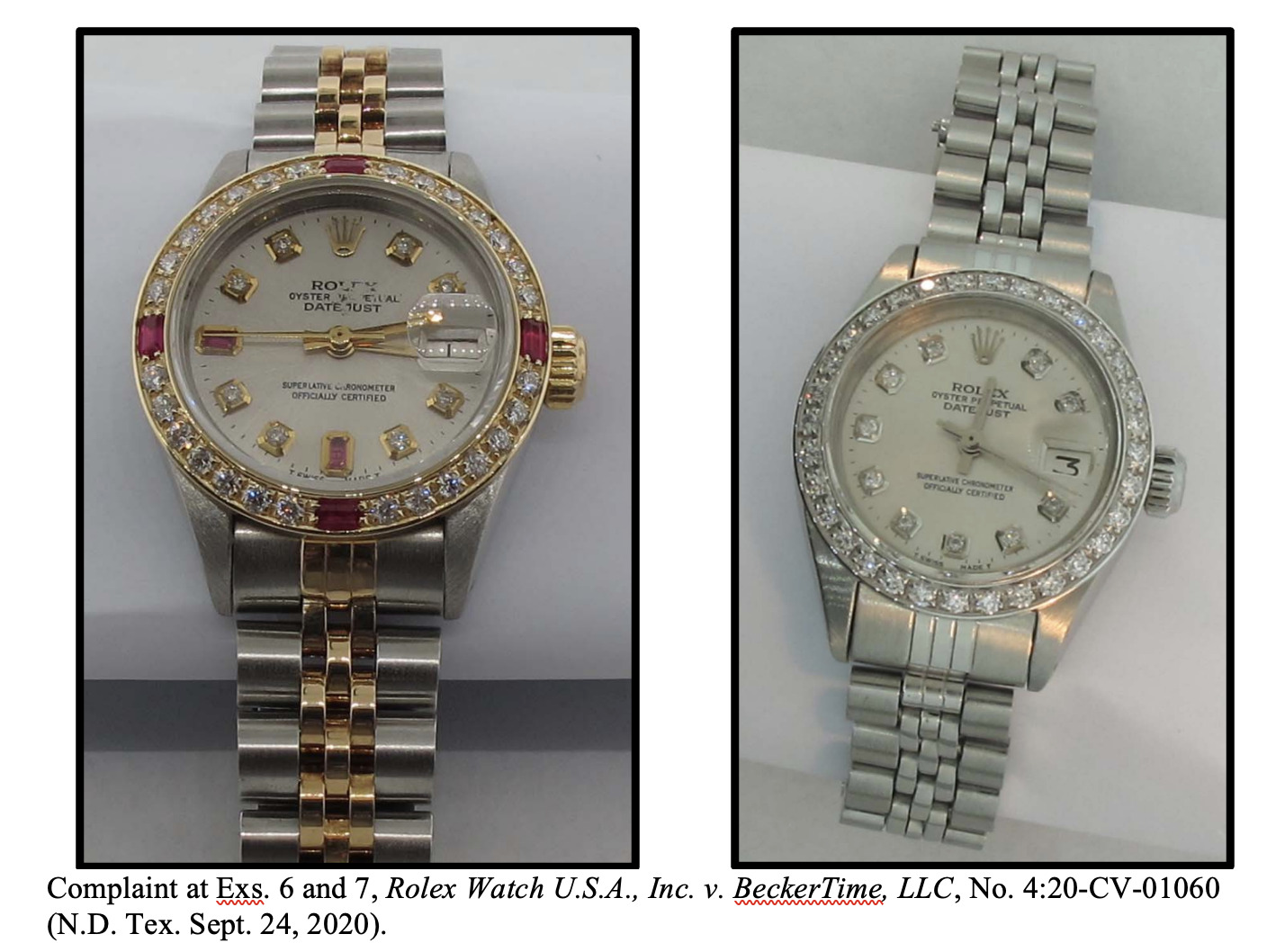

iii. Rolex Watch U.S.A., Inc. v. BeckerTime, LLC, No. 4:20-CV-01060, 2022 WL 286184

(N.D. Tex. Jan. 31, 2022)

The Northern District of Texas held that Rolex was entitled to a permanent injunction barring an upcycler from creating hybrid watches from Rolex and third-party parts—all the while claiming them to be “Genuine Rolex” watches. The district court determined that the upcycler’s use of Rolex’s trademarks constituted counterfeiting.

The at-issue watches sold by BeckerTime contained at least one Rolex trademark. BeckerTime applied aftermarket bezels (not made or endorsed by Rolex) to some of the at-issue watches, including bezels with added diamonds. BeckerTime sometimes applied aftermarket bands or straps (not made or endorsed by Rolex) to the at-issue watches that included a genuine Rolex clasp or buckle displaying Rolex’s trademarks. The parts BeckerTime added to the at-issue watches did not bear any markings indicating BeckerTime as the source. BeckerTime provided an “Authenticity Guarantee” for each at-issue watch. BeckerTime held itself out as a “Certified PreOwned Watch Dealer” with a “Rolex Certified Master Watchmaker.” But Rolex had never certified or endorsed BeckerTime, its watchmaker, or any of the watches that BeckerTime sells.

However, because Rolex’s attorneys had been aware of the upcycler’s activities (i.e., his importation of used Rolex watches) for at least 10 years before bringing suit, the district court denied Rolex the disgorgement of defendant’s profits based on laches. The court stated that Rolex’s undue delay had prejudiced the upcycler because it “would not have shifted its business model to be reliant on the sale of altered Rolex watches.” Photographs of examples of the allegedly infringing upcycled products at issue in this case appear below.

iv. Hamilton Int’l Ltd. v. Vortic LLC, 486 F. Supp. 3d 657

(S.D.N.Y. 2020), aff’d, 13 F.4th 264 (2d Cir. 2021)

The Southern District of New York held that wristwatches created using genuine parts from pocket watches originally made and sold in the United States from 1894 through 1950 under the Hamilton trademark were not likely to cause confusion as to their source. The district court observed that “[c]ourts in this Circuit have … found the adequacy of disclosure, or lack thereof, to be dispositive when determining the likelihood of confusion caused by a modified genuine product.” Accordingly, while the Hamilton marks were still evident on some of the original parts used by the defendant (e.g. the watch faces), indicia on the back of the watch identified the defendant as the source of those watches. The defendant’s advertisements and website also made clear the watches’ provenance. The Second Circuit affirmed the district court’s decision based largely upon Hamilton’s having failed to discharge the burden of proving the likelihood of confusion among reasonably prudent purchasers as to the source of Vortic’s watches. Photographs of examples of the allegedly infringing upcycled products at issue in this case appear below.

v. Rolex Watch U.S.A., Inc. v. Reference Watch LLC d/b/a La Californienne, No. 2:19-cv-09796-RGK-JPR (C.D. Cal. May 28, 2020)

The Central District of California entered a stipulated judgment in favor of Rolex, permanently enjoining upcycling company La Californienne from creating hybrid watches from Rolex and third-party parts. Defendant’s altered Rolex watches included refinished dials (some with diamonds) from which one or more of the Rolex registered trademarks had been removed and reapplied. Specifically, during the dial refinishing process, the CROWN DESIGN trademark emblem was removed from the dial, the dial surface was stripped of all paint and all printed Rolex registered trademarks, new paint was reapplied to the dial surface, the Rolex registered trademarks were reprinted on the dial, and the trademark emblem (sometimes repainted) was reattached to the dial. On some of the watches, Defendant also painted its name “La Californienne” and/or other embellishments onto the dial. Photographs of examples of the allegedly infringing upcycled products at issue in this case appear below.

Complaint at Ex. 6, Rolex Watch U.S.A., Inc. v. BeckerTime, LLC, No. 4:20-CV-01060 (N.D. Tex. Nov. 15, 2019).

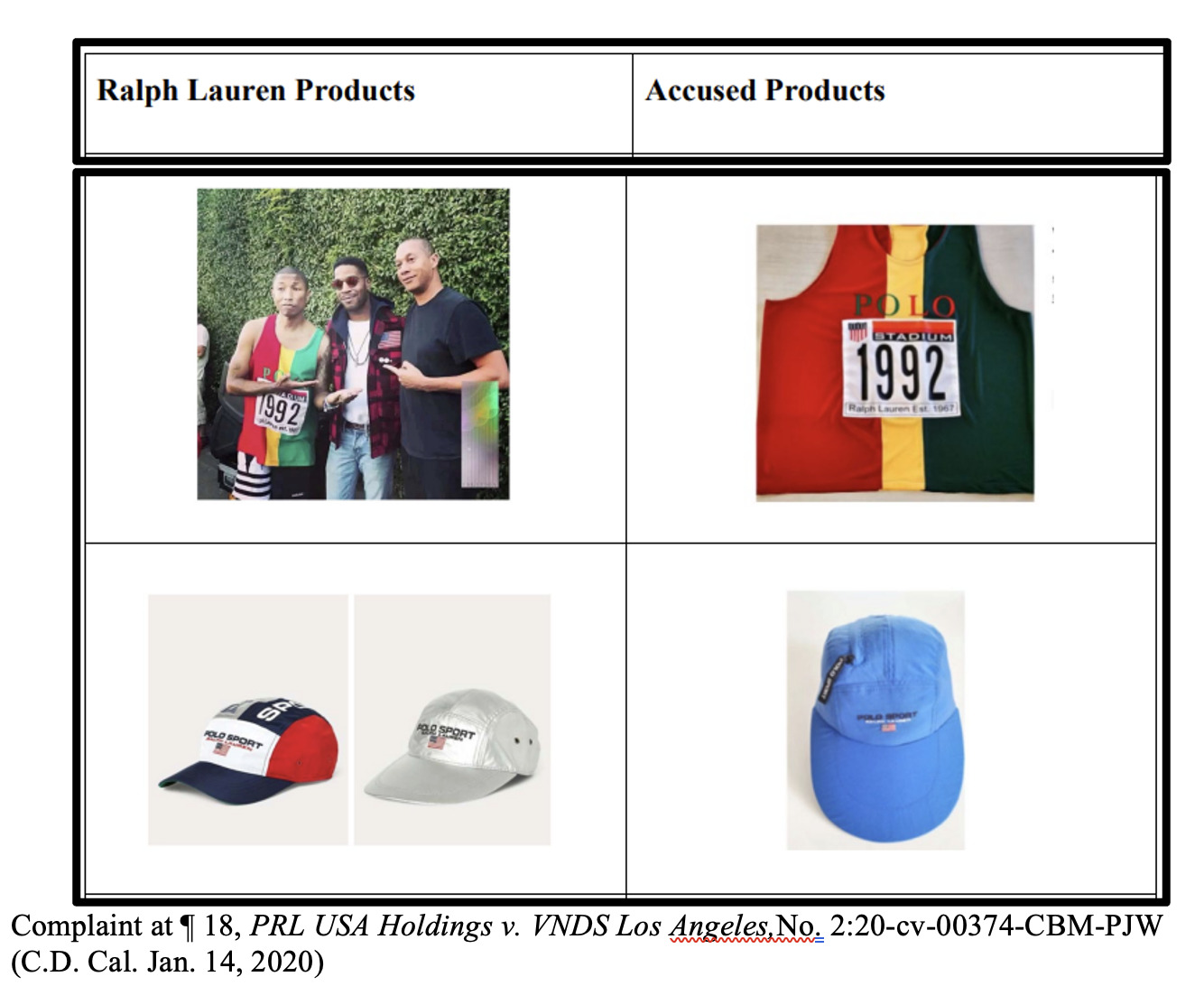

vi. PRL USA Holdings v. VNDS Los Angeles, No. 2:20-cv-00374-CBM-PJW

(C.D. Cal. Dec. 9, 2020)

Ralph Lauren filed a lawsuit for trademark infringement against a California-based company, VDNS. Some of the allegedly infringing products included a hat upcycled from authentic Ralph Lauren swim shorts. Since the resold goods were materially different from the original product, they fell outside the scope of first sale protection and amounted to infringement. The Central District of California issued a default judgment in Ralph Lauren’s favor for a permanent injunction and statutory damages in the amount of $800,000 under 15 U.S.C. § 1117(c), plus prejudgment interest. Photographs of representative examples of the allegedly infringing upcycled products at issue in this case appear below.

Brand Protection Measures

Sustainable Practices to Satisfy Market Demand

Some luxury brands have been proactively partnering or directly competing with upcyclers. For example, The RealReal and Atelier & Repairs have created “ReCollection 01,” which transforms old or damaged pieces from luxury brands into one-of-a-kind garments. Similarly, Altuzarra’s Re-Crafted Collection and Loewe’s The Surplus Project upcycle fabrics from previous collections to create new pieces. Relatedly, LVMH sells on its online shop called Nona Source unused fabrics from its high-end brands, including Louis Vuitton, Christian Dior, Givenchy, Stella McCartney, and Celine, among others, at bargain prices.

Enforcement

A brand faced with an infringing upcycler can utilize the following tools to protect its brands from misuse:

- “informal enforcement” through demand letters, business-to-business discussions, and/or take-down requests;

- a court order (injunction) that the defendant stop using the accused mark;

- an order requiring the destruction or forfeiture of infringing articles;

- monetary relief, including defendant’s profits, any damages sustained by the plaintiff, and the costs of the action; and

- an order that the defendant, in certain cases, pay the plaintiffs’ attorneys’ fees.

Sustainability Doesn’t Have to Be Confusing

As discussed above, upcycling helps further society’s general goal and desire for a more sustainable future, but it also poses business and legal concerns for brand owners. Trademarks are a powerful tool that brand owners can use to protect themselves against these concerns, such as post-sale confusion, brand dilution, and diversion of sales. The cases and the brand protection measures discussed above provide a framework for how brand owners can succeed against upcyclers who violate their branding rights

Image Source: Deposit Photos

Image ID: 88287952

Author: eyematrix

![[IPWatchdog Logo]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/themes/IPWatchdog%20-%202023/assets/images/temp/logo-small@2x.png)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/UnitedLex-May-2-2024-sidebar-700x500-1.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/Artificial-Intelligence-2024-REPLAY-sidebar-700x500-corrected.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/Patent-Litigation-Masters-2024-sidebar-700x500-1.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/WEBINAR-336-x-280-px.png)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/2021-Patent-Practice-on-Demand-recorded-Feb-2021-336-x-280.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/Ad-4-The-Invent-Patent-System™.png)

Join the Discussion

No comments yet.