California’s Proposed Fix to the Journalism Crisis Is Unconstitutional and Worse Than Socialism (Comments on the California Journalism Protection Act, CJPA)

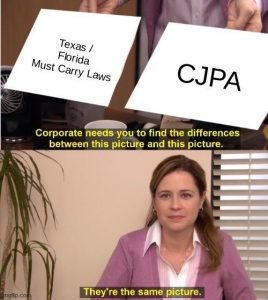

The California legislature is competing with states like Florida and Texas to see who can pass laws will be more devastating to the Internet. California’s latest entry into this Internet death-spiral is the California Journalism Protection Act (CJPA, AB 886). CJPA has passed the California Assembly and is pending in the California Senate.

The California legislature is competing with states like Florida and Texas to see who can pass laws will be more devastating to the Internet. California’s latest entry into this Internet death-spiral is the California Journalism Protection Act (CJPA, AB 886). CJPA has passed the California Assembly and is pending in the California Senate.

The CJPA engages with a critical problem in our society: how to ensure the production of socially valuable journalism in the face of the Internet’s changes to journalists’ business models? The bill declares, and I agree, that a “free and diverse fourth estate was critical in the founding of our democracy and continues to be the lifeblood for a functioning democracy….Quality local journalism is key to sustaining civic society, strengthening communal ties, and providing information at a deeper level that national outlets cannot match.” Given these stakes, politicians should prioritize developing good-faith and well-researched ways to facilitate and support journalism. The CJPA is none of that.

Instead, the CJPA takes an asinine, ineffective, unconstitutional, and industry-captured approach to this critical topic. The CJPA isn’t a referendum on the importance of journalism; instead, it’s a test of our legislators’ skills at problem-solving, drafting, and helping constituents. Sadly, the California Assembly failed that test.

Overview of the Bill

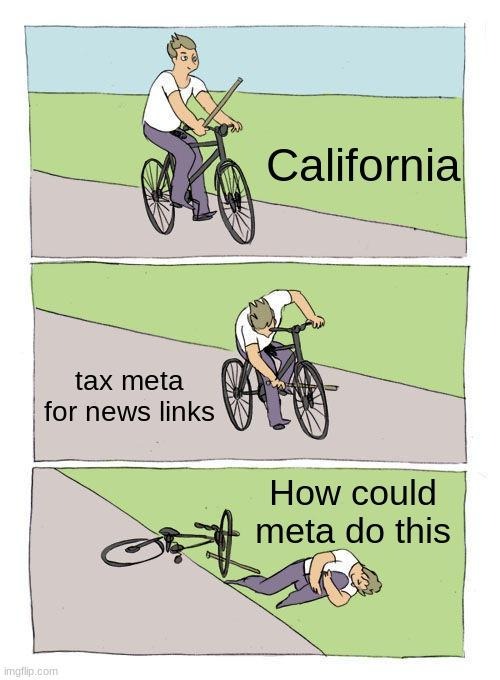

The CJPA would make some Big Tech services pay journalists for using snippets of their content and providing links to the journalists’ websites. This policy approach is sometimes called a “link tax,” but that’s a misnomer. Tax dollars go to the government, who can then allocate the money to (in theory) advance the public good—such as funding journalism.

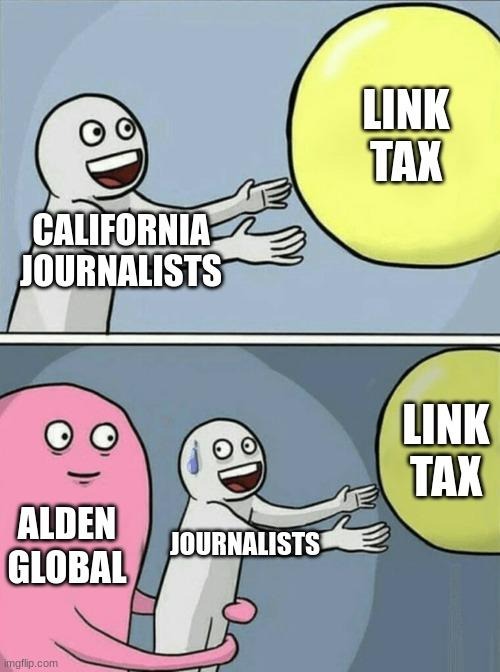

The CJPA bypasses the government’s intermediation and supervision of these cash flows. Instead, it pursues a policy worse than socialism. CJPA would compel some bigger online publishers (called “covered platforms” in the bill) to transfer some of their wealth directly to other publishers–intended to be journalistic operations, but most of the dollars will go to vulture capitalists’ stockholders and MAGA-clickbait outlets like Breitbart.

In an effort to justify this compelled wealth transfer, the bill manufactures a new intellectual property right–sometimes called an “ancillary copyright for press publishers“–in snippets and links and then requires the platforms to pay royalties (euphemistically called “journalism usage fee payments”) for the “privilege” of publishing ancillary-copyrighted material. The platforms aren’t allowed to reject or hide DJPs’ content, so they must show the content to their audiences and pay royalties even if they don’t want to.

The wealth-transfer recipients are called “digital journalism providers” (DJPs). The bill contemplates that the royalty amounts will be set by an “arbitrator” who will apply baseball-style “arbitration,” i.e., the valuation expert picks one of the parties’ proposals. “Arbitrator” is another misnomer; the so-called arbitrators are just setting valuations.

DJPs must spend 70% of their royalty payouts on “news journalists and support staff,” but that money won’t necessarily fund NEW INCREMENTAL journalism. The bill explicitly permits the money to be spent on administrative overhead instead of actual journalism. With the influx of new cash, DJPs can divert their current spending on journalists and overhead into the owners’ pockets. Recall how the COVID stimulus programs directly led to massive stock buybacks that put the government’s cash into the hands of already-wealthy stockholders–same thing here. Worse, journalist operations may become dependent on the platforms’ royalties, which could dry up with little warning (e.g., a platform could drop below CJPA’s statutory threshold). We should encourage journalists to build sustainable business models. CJPA does the opposite.

DJPs must spend 70% of their royalty payouts on “news journalists and support staff,” but that money won’t necessarily fund NEW INCREMENTAL journalism. The bill explicitly permits the money to be spent on administrative overhead instead of actual journalism. With the influx of new cash, DJPs can divert their current spending on journalists and overhead into the owners’ pockets. Recall how the COVID stimulus programs directly led to massive stock buybacks that put the government’s cash into the hands of already-wealthy stockholders–same thing here. Worse, journalist operations may become dependent on the platforms’ royalties, which could dry up with little warning (e.g., a platform could drop below CJPA’s statutory threshold). We should encourage journalists to build sustainable business models. CJPA does the opposite.

Detailed Analysis of the Bill Text

Who is a Digital Journalism Provider (DJP)?

A print publisher qualifies as a DJP if it:

- “provide[s] information to an audience in the state.” Is a single reader in California an “audience”? By mandating royalty payouts despite limited ties to California, the bill ensures that many/most DJPs will not be California-based or have any interest in California-focused journalism.

- “performs a public information function comparable to that traditionally served by newspapers and other periodical news publications.” What publications don’t serve that function?

- “engages professionals to create, edit, produce, and distribute original content concerning local, regional, national, or international matters of public interest through activities, including conducting interviews, observing current events, analyzing documents and other information, or fact checking through multiple firsthand or secondhand news sources.” This is an attempt to define “journalists,” but what publications don’t “observe current events” or “analyze documents or other information”?

- updates its content at least weekly.

- has “an editorial process for error correction and clarification, including a transparent process for reporting errors or complaints to the publication.”

- has:

- $100k in annual revenue “from its editorial content,” or

- an ISSN (good news for me; my blog ISSN is 2833-745X 🤑), or

- is a non-profit organization

- 25%+ of content is about “topics of current local, regional, national, or international public interest.” Again, what publications don’t do this?

- is not foreign-owned, terrorist-owned, etc.

If my blog qualifies as an eligible DJP, the definition of DJPs is surely over-inclusive.

Broadcasters qualify as DJPs if they:

- have the specified FCC license,

- engage journalists (like the factor above),

- update content at least weekly, and

- have error correction processes (like the factor above).

Who is a Covered Platform?

A service is a covered platform if it:

- Acquires, indexes, or crawls DJP content,

- “Aggregates, displays, provides, distributes, or directs users” to that content, and

- Either

- Has 50M+ US-based MAUs or subscribers, or

- Its owner has (1) net annual sales or a market cap of $550B+ OR (2) 1B+ worldwide MAUs.

(For more details about the problems created by using MAUs/subscribers and revenues/market cap to measure size, see this article).

How is the “Journalism Usage Fee”/Ancillary Copyright Royalty Computed?

The CJPA creates a royalty pool of the “revenue generated through the sale of digital advertising impressions that are served to customers in the state through an online platform.” I didn’t understand the “impressions” reference. Publishers can charge for advertising in many ways, including ad impressions (CPM), clicks, actions, fixed fee, etc. Does the definition only include CPM-based revenue? Or all ad revenue, even if impressions aren’t used as a payment metric? There’s also the standard problem of apportioning ad revenue to “California.” Some readers’ locations won’t be determinable or will be wrong; and it may not be possible to disaggregate non-CPM payments by state.

Each platform’s royalty pool is reduced by a flat percentage, nominally to convert ad revenues from gross to net. This percentage is determined by a valuation-setting “arbitration” every 2 years (unless the parties reach an agreement). The valuation-setting process is confusing because it contemplates that all DJPs will coordinate their participation in a single “arbitration” per platform, but the bill doesn’t provide any mechanisms for that coordination. As a result, it appears that DJPs can independently band together and initiate their own customized “arbitration,” which could multiply the proceedings and possibly reach inconsistent results.

The bill tells the valuation-setter to:

- Ignore any value conferred by the platform to the DJPs due to the traffic referrals, “unless the covered platform does not automatically access and extract information.” This latter exclusion is weird. For example, if a user posts a link to a third-party service, the platform could argue that this confers value to the DJP only if the platform doesn’t show an automated preview.

- Note: In a typical open-market transaction, the parties always consider the value they confer on each other when setting the price. By unbalancing those considerations, the CJPA guarantees the royalties will overcompensate DJPs.

- “Consider past incremental revenue contributions as a guide to the future incremental revenue contribution” by each DJP. No idea what this means.

- Consider “comparable commercial agreements between parties granting access to digital content…[including] any material disparities in negotiating power between the parties to those commercial agreements.” I assume the analogous agreements will come from music licensing?

Each DJP is entitled to a percentage, called the “allocation share,” of the “net” royalty pool. It’s computed using this formula: (the number of pages linking to, containing, or displaying the DJP’s content to Californians) / (the total number of pages linking to, containing, or displaying any DJP’s content to Californians). Putting aside the problems with determining which readers are from California, this formula ignores that a single page may have content from multiple DJPs. Accordingly, the allocation share percentages cumulatively should add up to over 100% of the net royalty pool calculated by the valuation-setters. In other words, the formula ensures the unprofitability of publishing DJP content. For-profit companies typically exit unprofitable lines of business.

Elimination of Platforms’ Editorial Discretion

The CJPA has an anti-“retaliation” clause that nominally prevents platforms from reducing their financial exposure:

(a) A covered platform shall not retaliate against an eligible digital journalism provider for asserting its rights under this title by refusing to index content or changing the ranking, identification, modification, branding, or placement of the content of the eligible digital journalism provider on the covered platform.

(b) An eligible digital journalism provider that is retaliated against may bring a civil action against the covered platform.

(c) This section does not prohibit a covered platform from, and does not impose liability on a covered platform for, enforcing its terms of service against an eligible journalism provider.

This provision functions as a mandatory must-carry provision. It forces platforms to carry content they don’t want to carry and don’t think is appropriate for their audience–at peril of being sued for retaliation. In other words, any editorial decision that is adverse to any DJP creates a non-trivial risk of a lawsuit alleging that the decision was retaliatory. It doesn’t really change the calculus if the platform might ultimately prevail in the lawsuit; the costs and risks of being sued are enough to prospectively distort the platform’s decision-making.

[Note: section (c) doesn’t negate this issue at all. It simply converts a litigation battle over retaliation into a battle over whether the DJP violated the TOS. Platforms could try to eliminate the anti-retaliation provision by drafting TOS provisions broad enough to provide them with total editorial flexibility. However, courts might consider such broad drafting efforts to be bad faith non-compliance with the bill. Further, unhappy DJPs will still claim that broad TOS provisions were selectively enforced against them due to the platform’s retaliatory intent, so even tricky TOS drafting won’t eliminate the litigation risk.]

Thus, CJPA rigs the rules in favor of DJPs. The financial exposure from the anti-retaliation provision, plus the platform’s reduced ability to cater to the needs of its audience, further incentivizes platforms to drop all DJP content entirely or otherwise substantially reconfigure their offerings.

Limitations on DJP Royalty Spending

DJPs must spend 70% of the royalties on “news journalists and support staff.” Support staff includes “payroll, human resources, fundraising and grant support, advertising and sales, community events and partnerships, technical support, sanitation, and security.” This indicates that a DJP could spend the CJPA royalties on administrative overhead, spend a nominal amount on new “journalism,” and divert all other revenue to its capital owners. The CJPA doesn’t ensure any new investments in journalism or discourage looting of journalist organizations. Yet, I thought supporting journalism was CJPA’s raison d’être.

Why CJPA Won’t Survive Court Challenges

If passed, the CJPA will surely be subject to legal challenges, including:

Restrictions on Editorial Freedom. The CJPA mandates that the covered platforms must publish content they don’t want to publish–even anti-vax misinformation, election denialism, clickbait, shill content, and other forms of pernicious or junk content.

Florida and Texas recently imposed similar must-carry obligations in their social media censorship laws. The Florida social media censorship law specifically restricted platforms’ ability to remove journalist content. The 11th Circuit held that the provision triggered strict scrutiny because it was content-based. The court then said the journalism-protection clause failed strict scrutiny–and would have failed even lower levels of scrutiny because “the State has no substantial (or even legitimate) interest in restricting platforms’ speech…to ‘enhance the relative voice’ of…journalistic enterprises.” The court also questioned the tailoring fit. I think CJPA raises the same concerns. For more on this topic, see Ashutosh A. Bhagwat, Why Social Media Platforms Are Not Common Carriers, 2 J. Free Speech L. 127 (2022).

Florida and Texas recently imposed similar must-carry obligations in their social media censorship laws. The Florida social media censorship law specifically restricted platforms’ ability to remove journalist content. The 11th Circuit held that the provision triggered strict scrutiny because it was content-based. The court then said the journalism-protection clause failed strict scrutiny–and would have failed even lower levels of scrutiny because “the State has no substantial (or even legitimate) interest in restricting platforms’ speech…to ‘enhance the relative voice’ of…journalistic enterprises.” The court also questioned the tailoring fit. I think CJPA raises the same concerns. For more on this topic, see Ashutosh A. Bhagwat, Why Social Media Platforms Are Not Common Carriers, 2 J. Free Speech L. 127 (2022).

Note: the Florida bill required platforms to carry the journalism content for free. CJPA would require platforms to pay for the “privilege” of being forced to carry journalism content, wanted or not. CJPA’s skewed economics denigrate editorial freedom even more grossly than Florida’s law.

Copyright Preemption. The CJPA creates copyright-like protection for snippets and links. Per 17 USC 301 (the copyright preemption clause), only Congress has the power to provide copyright-like protection for works, including works that do not contain sufficient creativity to qualify as an original work of authorship. Content snippets and links individually aren’t original works of authorship, so they do not qualify for federal copyright protection at the federal or state level; while any compilation copyright is within federal copyright’s scope and therefore is also off-limits to state protection.

The CJPA governs the reproduction, distribution, and display of snippets and links, and the federal copyright law governs those activities in 17 USC 106. CJPA’s provisions thus overlap with 106’s scope, but the works are within the scope of federal copyright law. This is not permitted by federal copyright preemption.

Section 230. Most or all of the snippets/links governed by the CJPA will constitute third-party content, including search results containing third-party content and user-submitted links where the platform automatically fetches a preview from the DJP’s website. Thus, CJPA runs afoul of Section 230 in two ways. First, it treats the covered platforms as the “publishers or speakers” of those snippets and links for purposes of the allocation share. Second, the anti-retaliation claim imposes liability for removing/downgrading third-party content, which courts have repeatedly said is covered by Section 230 (in addition to the First Amendment).

DCC. I believe the Dormant Commerce Clause should always apply to state regulation of the Internet. In this case, the law repeatedly contemplates the platforms determining the location of California’s virtual borders, which will always have an error rate that cannot be eliminated. Those errors guarantee that the law reaches activity outside of California.

Takings. I’m not a takings expert, but a government-compelled wealth transfer from one private party to another sounds like the kind of thing our country’s founders would have wanted to revolt against.

Conclusion

Other countries have attempted “link taxes” like CJPA. I’m not aware of any proof that those laws have accomplished their goal of enhancing local journalism. Knowing the track record of global futility, why do the bill’s supporters think CJPA will achieve better results? Because of their blind faith that the bill will work exactly as they anticipate? Their hatred of Big Tech? Their desire to support journalism, even if it requires using illegitimate means?

Our country absolutely needs a robust and well-functioning journalism industry. Instead of making progress towards that vital goal, we’re wasting our time futzing with crap like CJPA.

For more reasons to oppose the CJPA, see the Chamber of Progress page.

A Few More CJPA Memes

[Reminder: I’m retiring the phrase “link tax” in favor of “government-compelled wealth transfer.”]

Pingback: California’s Journalism Protection Act Is An Unconstitutional Clusterfuck Of Terrible Lawmaking | Techdirt()

Pingback: “California Journalism Preservation Act” rewards looters, not communities – Dan Gillmor()

Pingback: Why I Oppose the California Journalism Protection Act (the Short Version) - Technology & Marketing Law Blog()