by Dennis Crouch

In patent law, product copying can serve as indirect evidence of non-obviousness. A pending petition before the Supreme Court asks a similar question in the trademark realm – to what extent does copying of a product serve as evidence of secondary meaning of the product associated trade dress. Trendily Furniture, LLC v. Jason Scott Collection, Inc., 21-16978 (Supreme Court 2023). This is particularly important in the product design arena because evidence of secondary meaning must be proven before it is protectable as trade dress.

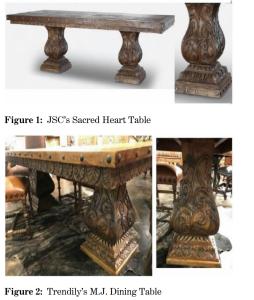

JSC designs and manufactures high-end furniture, primarily large, heavy-set pieces made of reclaimed teak and embellished with detailed wood carvings and metal designs. JSC sued Trendily Furniture for copying three of its furniture designs that featured this style. The trade dress dispute here is over the is over the overall look and design of these three ornate furniture pieces from JSC.

All of the circuit courts agree that copying can serve as evidence of secondary meaning. The circuits are split, however, on whether the copying must be accompanied by some intent to free-ride on customer goodwill or otherwise confuse customers via passing-off.

The petition for certiorari outlines 5 distinct approaches to the copying-intent issue taken by the various circuit courts of appeal:

- The 7th, 1st and 10th Circuits hold copying alone is legally irrelevant, unless the defendant also specifically “intended to confuse consumers and pass off its product as the plaintiff’s.” Mere intentional copying alone has no bearing.

- The 8th, 3rd and 11th Circuits hold copying may support an inference of secondary meaning, but no inference arises if there was some “neutral,” non-source-confusion reason for the copying.

- The 5th Circuit treats intentional copying as relevant but simply weighs it along with other factors.

- The 9th and 6th Circuits hold intentional copying alone, even absent proof of intent to create customer confusion, “strongly supports an inference of secondary meaning,” based on the logic that “‘[t]here is no logical reason for the precise copying save an attempt to realize upon a secondary meaning.’”

- The 4th Circuit goes even further to apply a “presumption of secondary meaning” from intentional copying regardless of proof of intent-to-confuse.

In Trendily, the 9th Circuit applied its rule to affirm judgment for the trade dress holder. The defendant admitted asking its Indian factory to manufacture exact copies of the plaintiff’s furniture based on photos, which it then sold under its own brand to some of the plaintiff’s own retailers. App., infra, 3a. The district court and 9th Circuit relied predominantly on this intentional copying to find secondary meaning acquired. On appeal, the 9th Circuit affirmed this holding that “[p]roof of copying strongly supports an inference of secondary meaning” because “[t]here is no logical reason for the precise copying save an attempt to realize upon a secondary meaning.”

In its petition, Trendily Furniture argues the intentional copying rationale is “flawed” and inconsistent with precedent recognizing that “product design almost invariably serves purposes other than source identification” – such that copying will often aim to “exploit” desirable features rather than create confusion.

I want to be clear here for a moment and point out a weak aspect of Trendily’s case. The arguments here focus on the question of whether or not the plaintiff has any protectable trade dress. Even if the answer is ‘yes,’ the plaintiff will still have to prove a likelihood of confusion between its product and the knock-off. Still, there are important competing interests — how much do we want to want the scale to weigh in favor of competition or against free-riding. My understanding is that all of the circuits permit an accused infringer to show evidence pro-competitive reasons for copying that are distinct deceiving consumers or free-riding off the sources acquired significance. The difference then is that some circuits create a presumption of that the copying is pro competitive absent proof otherwise, while others more readily infer bad faith.

The mark holder originally waived its right to respond, but a response was requested by the Justices. That responsive brief is due December 13, 2023.