A botched attempt to target young gamers lands the insurance company in court, as Atari sues over a classic console’s unauthorized ad appearance. It’s a mistake that could have been avoided.

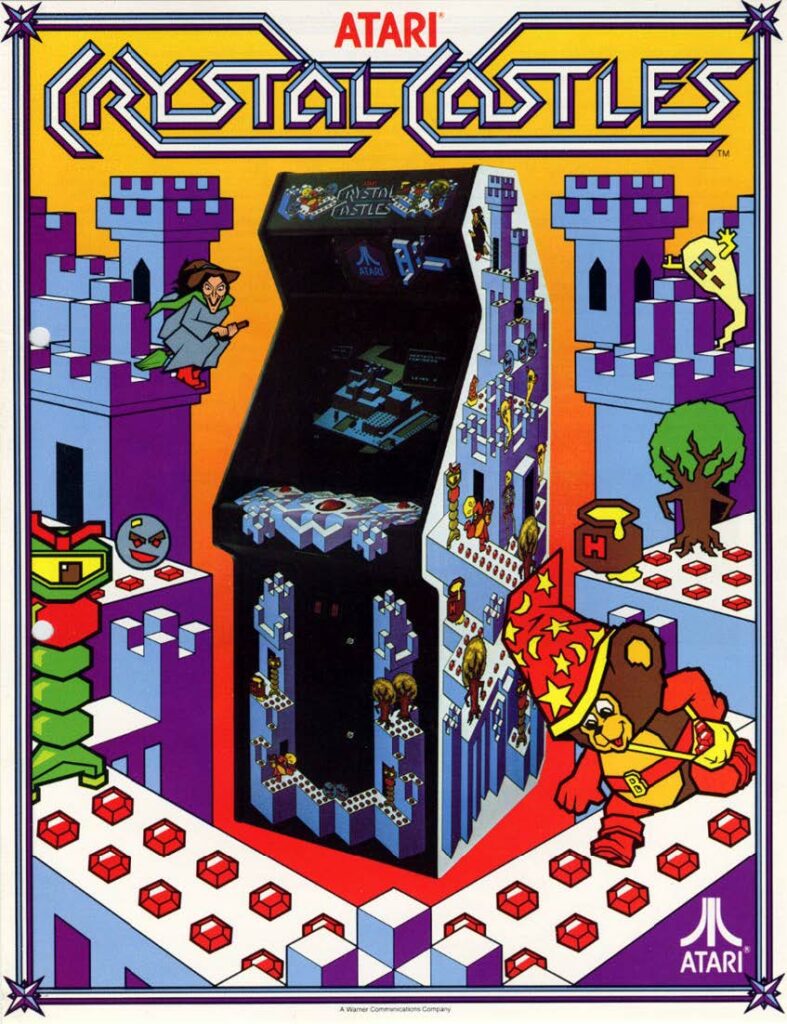

Video game publisher Atari Interactive has launched a copyright infringement lawsuit against State Farm, claiming that the insurer improperly appropriated artwork from Atari’s 1983 arcade game “Crystal Castles” for an advertising campaign as part of a “cynical plot” to resonate with fickle millennial and Gen Z consumers.

Atari Interactive v. State Farm

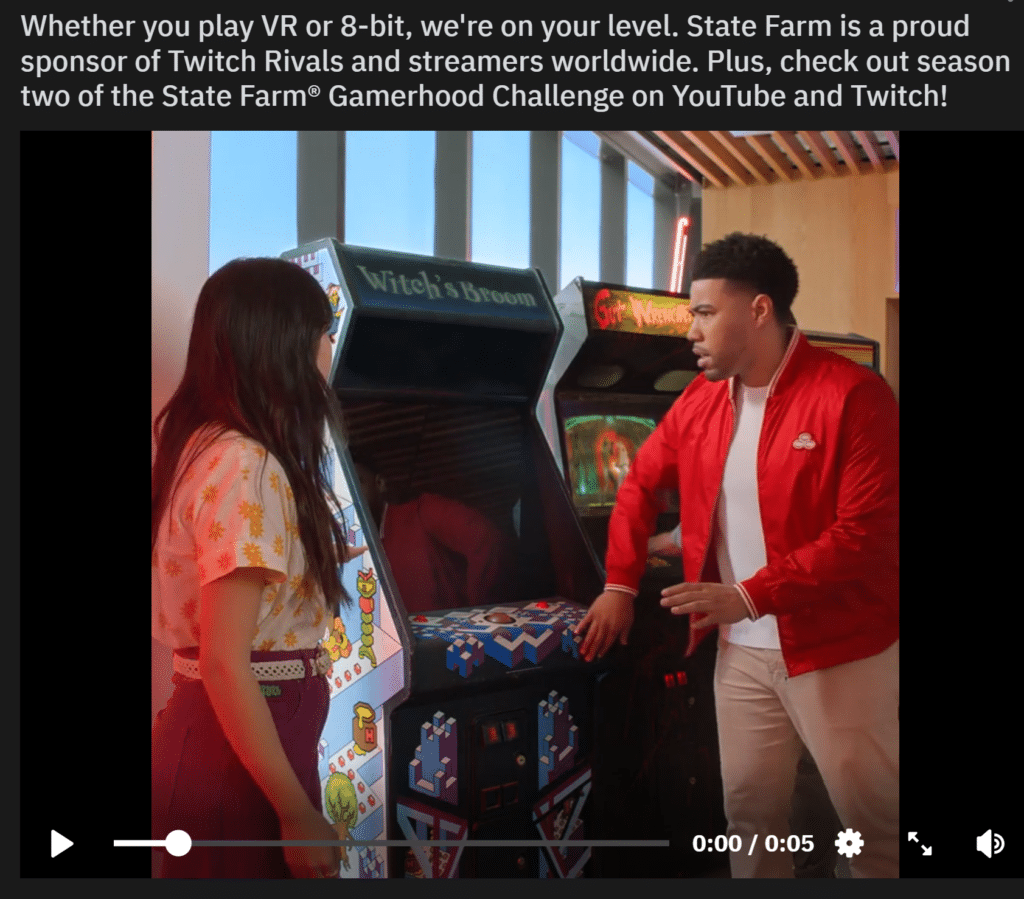

Atari’s complaint (read here) accuses State Farm and its ad agencies of engaging in “intentional, yet careless and haphazard efforts to conceal their infringement” by replacing the words “Crystal Castles” with “Witch’s Broom” on the console’s marquee while leaving the graphics on the front and side of the arcade cabinet intact, thereby “unlawfully associating Atari’s iconic intellectual property and cultural relevance with State Farm’s insurance business.” To make matters worse, State Farm’s resident do-gooder “Jake” lands a Fonzie-style smack on the Crystal Castles machine to get it working—“suggesting falsely and disparagingly to consumers that Atari’s cabinets are low-quality, faulty, and/or unreliable.”

Half-Measures, Meet Full-Blown Lawsuit

The charge that State Farm’s infringement was both deliberate and careless is a stretch, although probably no more so than State Farm thinking that a commercial depicting a 1980s arcade game was the key to getting young people to buy auto insurance. I chalk this up to a sloppy clearance job on the part of State Farm’s lawyers and ad agencies rather than some stealthy plot to trade on all that valuable Crystal Castles goodwill. Still, State Farm ignored the timeless advice of Mike Ehrmantraut by choosing a half measure when it should have just obscured the whole video game cabinet—or better yet, the company could have scrapped the whole idea of using decades-old arcade games to hawk insurance to twenty-somethings and hired a few Twitch streamers instead.

Atari isn’t blameless either. Its lawsuit comes across as an opportunistic attempt to profit from State Farm’s mistake rather than a legitimate effort to protect its copyright from real market harm. I suspect the vast majority of people who viewed State Farm’s ad didn’t even notice the Crystal Castles artwork, let alone know where it came from.

State Farm Plans, the Internet Laughs

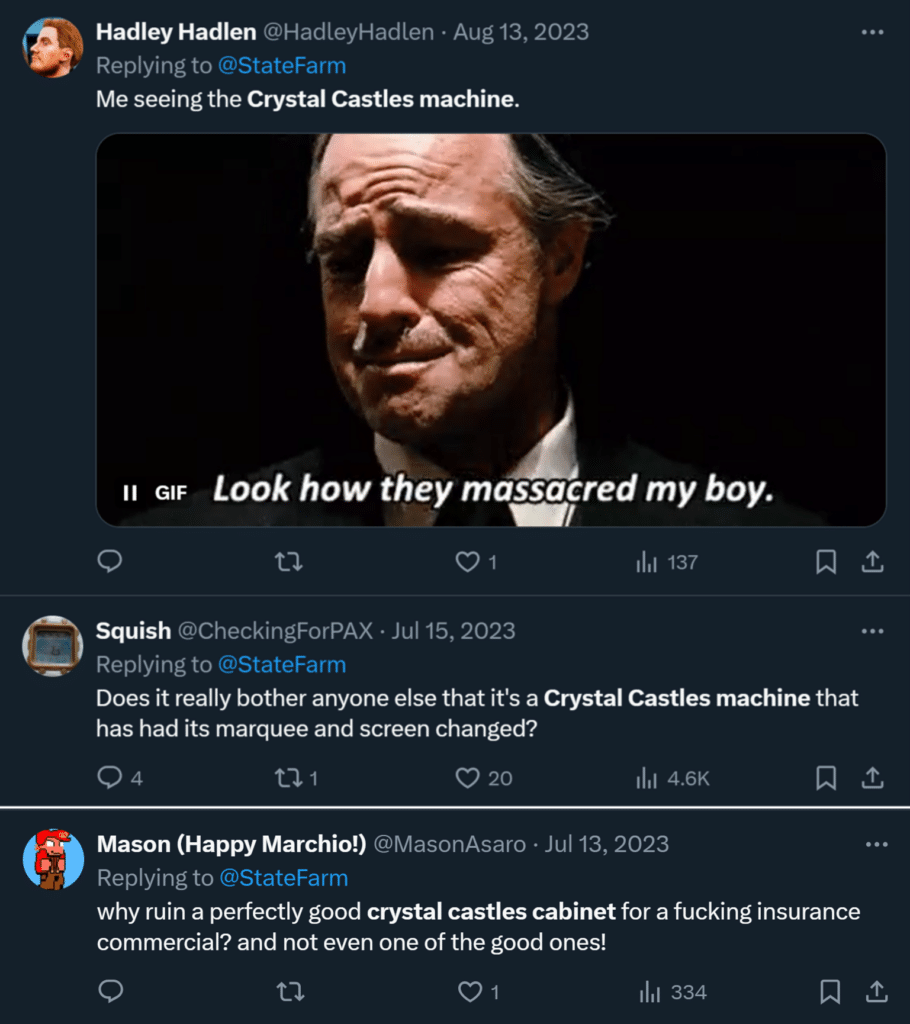

That said, if you’re going to pander to gamers on social media, you have to expect scrutiny and snarky comments. In this case, a handful of eagle-eyed observers took to Reddit and Twitter to excoriate State Farm’s attempt at relevance:

And my personal favorite:

State Farm Posts a New Version of the Ad . . .

Shortly after being publicly shamed (and likely in receipt of a demand letter from Atari’s lawyers), State Farm swapped out the offending artwork from its advertisement—something it should have done all along. Here’s the new commercial, sans Crystal Castles artwork (but still no CRT screen):

. . . And Still Gets Sued

State Farm’s revised ad is still hacky and pandering, but at least it’s not infringing. That should have been the end of this sorry saga, except that now, five months later, Atari has filed a federal lawsuit against State Farm and its ad agencies. Atari asserts claims not only for copyright infringement but also “business disparagement,” unfair competition and false advertising as well. Among other things, Atari alleges that its reputation and goodwill have been damaged, pointing to consumers who “expressed negative reactions to the perception that a cultural icon like Atari was commercially associated with an insurance conglomerate like State Farm.”

It’s certainly understandable that Atari wouldn’t want to be associated with an insurance company (as opposed to being known for the worst video game of all time), but as the social media posts above make clear, consumer criticism was directed at State Farm, not Atari. And while State Farm did technically reproduce Atari’s copyrighted artwork in its advertisement, it all seems like much ado about nothing. Which brings us to . . .

The Legal Stuff

The De Minimis Defense

As I’ve discussed before, there’s a whole doctrine with a fancy Latin name reserved for situations in which copying is insignificant enough to fall below the threshold of substantial similarity—de minimis non curat lex (“the law does not concern itself with trifles”).

The de minimis defense isn’t often discussed in copyright opinions because lawsuits aren’t typically brought over relatively inconsequential instances of copying. The doctrine has occasionally been invoked if a defendant’s unauthorized copying is sufficiently trivial—when a plaintiff’s work appears only briefly, is obscured, out of focus, or otherwise does not comprise the focal point of the new work in which it appears—but still draws a lawsuit.

For example, just last year, a court relied in part on the de minimis doctrine to dismiss a copyright infringement case brought by a photographer whose series of “Airportraits” briefly appeared in a Billie Eilish documentary on AppleTV+. These photos didn’t feature prominently in the film, but rather were “obstructed, out of focus, under low lighting, displayed at an angle to the viewer, and at all times in the background.”

Other cases involving successful applications of the de minimis doctrine include Gottlieb v. Paramount Pictures, in which the plaintiff’s “Silver Slugger” pinball machine appeared for a few seconds in the background of a scene from the otherwise forgettable Mel Gibson rom-com What Women Want. In another recent case, the court in Solid Oak Sketches v. 2K Games held that the use of NBA players’ tattoos in the popular “NBA 2K” video games was de minimis, pointing out that the tattoos appeared only fleetingly, and comprised only 0.000286% to 0.000431% of the total game data.

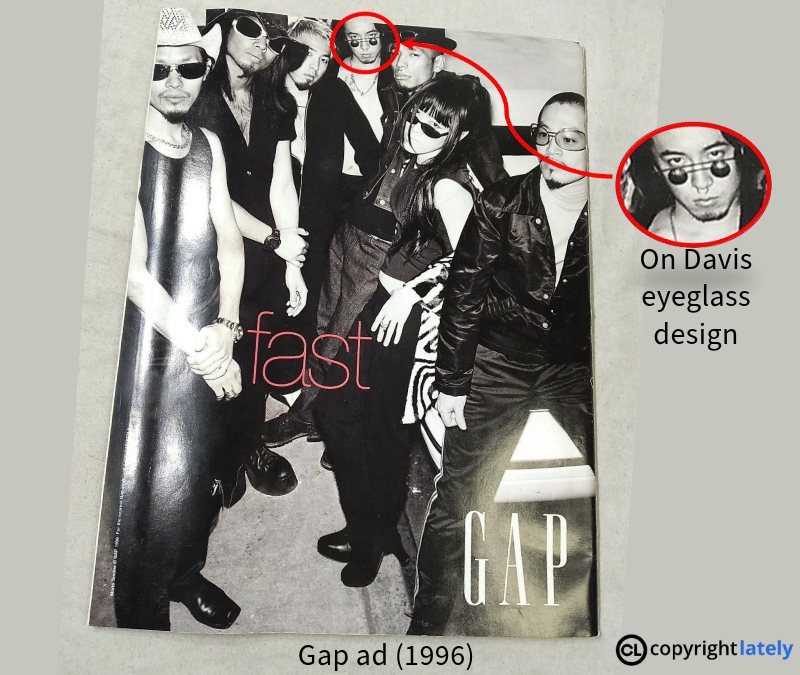

The bad news for State Farm is that courts don’t apply the de minimis doctrine as often as you might think they would—even in cases involving relatively trivial or insignificant copying. Case in point is the Second Circuit’s 2001 opinion in On Davis v. The Gap, Inc. Davis is an eyeglass designer who sued the mall store retailer Gap for a print ad that depicted a model wearing a pair of the plaintiff’s glasses in an advertisement. The court rejected Gap’s de minimis argument on the grounds that the plaintiff’s glasses had a particularly unique and distinctive design and were “highly noticeable.” Here’s a copy of the ad if you want to judge for yourself:

The artwork on the Crystal Castles cabinet is certainly more noticeable in State Farm’s commercial than Davis’s glasses were in the Gap ad, likely making a de minimis defense DOA.

Fair Use

Fair use would typically be the other go-to defense in a case like Atari Interactive v. State Farm, but as courts continue to feel out the boundaries of last year’s Warhol decision, it’s become much more difficult to prevail on a fair use defense, especially when a secondary work is used for a commercial purpose.

Just a few days ago, the Tenth Circuit Court of Appeals reversed a district court’s fair use finding in a case in which plaintiff’s videos of Tiger King star Joe Exotic were used in an episode of the Netflix Covid staple. The court found that the first fair use factor (purpose and character of the use) weighed strongly in favor of the plaintiff in light of the commercial nature of Tiger King and the lack of any commentary on the plaintiff’s video itself (as opposed to the defendants’ use of the video to comment on Joe Exotic). While the court didn’t go so far as to say that Netflix’s use of the clip was not covered by fair use, it did require the streamer to bear the burden of showing the absence of any market harm to the plaintiff.

There are certainly fair use arguments that State Farm could make—including that the use of Crystal Castles in set decor doesn’t serve as a market substitute for anyone who would otherwise want to play or buy the game itself—although State Farm’s use does plausibly usurp the licensing market for use of the game in advertisements or set dressing. At the end of the day, there’s no good reason for State Farm to litigate this case. Its best bet is to try to settle as quickly and cheaply as possible and chalk it up to a learning experience.

The Bottom Line

If there’s a silver lining to this whole fiasco, Atari’s lawsuit highlights the importance of ensuring that any props or set pieces appearing in advertising are either cleared (by obtaining permission from the rightsholders) or else appropriately obscured or eliminated before an ad is finalized. The idea isn’t to successfully defend a copyright lawsuit but to avoid an unforced error in the first place.

Just like thousands of other parties to routine copyright infringement cases, I expect that Atari and State Farm will settle this one relatively quickly out of court. While Atari’s lawsuit may be somewhat opportunistic, there isn’t a strong enough defense—or enough at stake—for State Farm to fight. Still, this all could have easily been avoided if someone from State Farm’s creative or legal teams had engaged in standard rights clearance procedures. A good media liability insurance policy could also help. Just ask Jake—he’ll find you one.

As always, I’d love to know what you think. Hit me up in the comments below or on your least detested social media platform. In the meantime, here’s a copy of Atari’s lawsuit for your 8-bit enjoyment:

View Fullscreen

2 comments

Looks like you have the wrong doc – linking to a decision in the Tiger King case rather than the complaint.

Whoops – fixed – thanks for letting me know!