Think Kiwi Farms Is Legally Unassailable? Copyright Law Might Disagree–Greer v. Moon

Kiwi Farms, operated by Joshua Moon, is best known for coordinating cyberattacks on individuals, especially people with disabilities. Few people would lament the site’s demise, but to date it has avoided legal exposure (1, 2) and survived multiple deplatformings (e.g., CloudFlare’s block). But if you really want Kiwi Farms gone, have you considered using copyright law for its censorial power?

The Court Opinion

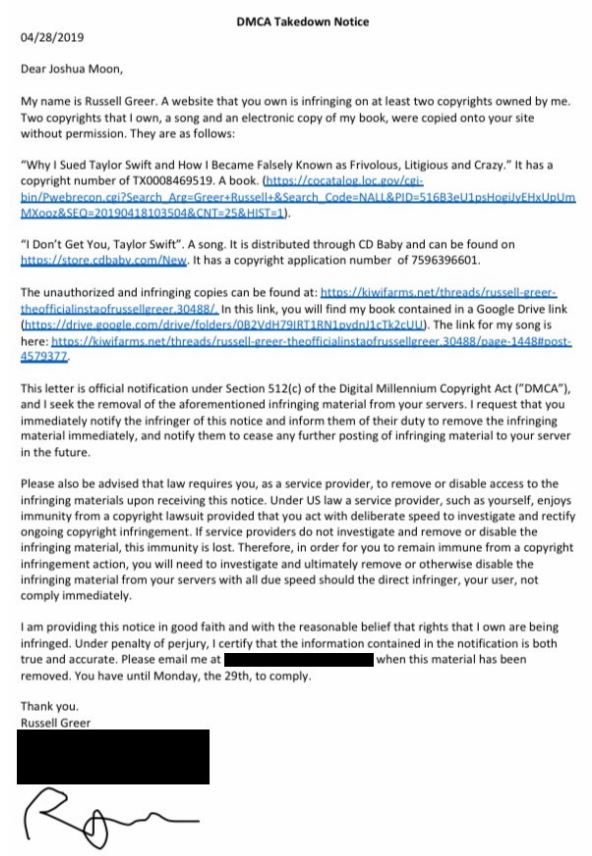

Greer was a target of one of Kiwi Farms’ attacks. He self-published a book about the experience (“Why I Sued Taylor Swift and How I Became Falsely Known as Frivolous, Litigious and Crazy“). “Kiwi Farms users provided a Google Drive link to a full copy of Mr. Greer’s book.” Greer emailed Moon asking to remove the book. Moon posted the email for further mocking. Greer also wrote a song (“I Don’t Get You, Taylor Swift”), and “his new song had been uploaded to Kiwi Farms.” Greer then sent Moon the following DMCA takedown notice:

Moon didn’t remove any content in response to this notice. Instead, he publicly posted the DMCA takedown notice for further mocking. Greer sued Moon and Kiwi Farms for contributory copyright infringement and other claims. The district court dismissed the contributory claim because the defendants didn’t materially contribute to the infringement. The appellate court revives the claim.

Moon didn’t remove any content in response to this notice. Instead, he publicly posted the DMCA takedown notice for further mocking. Greer sued Moon and Kiwi Farms for contributory copyright infringement and other claims. The district court dismissed the contributory claim because the defendants didn’t materially contribute to the infringement. The appellate court revives the claim.

[Note: Greer filed the complaint pro se, but he retained counsel for the appeal. The ruling is confusing in part because of the court’s deference to the pro se complaint.]

Direct Infringement. The court says these allegations are sufficient for direct copyright infringement:

Mr. Greer alleged he discovered the book “had been illegally put onto Kiwi Farms” in January 2018. “Somebody,” he explained, “created a copy of [his] book and put it in a Google Drive that is accessible on Kiwi Farms.” The complaint also included allegations “[o]ther users on Kiwi Farms have created unauthorized audio recordings of” the book “and have put them on various sites.” Kiwi Farms, Mr. Greer continued, “has links to these audio recordings.” As to the song, Mr. Greer alleged he found an “MP3 of his song was . . . on Kiwi Farms” in April 2019. A Kiwi Farms user posted the song with the comment “Enjoy this repetitive turd.” Another user commented, “Upload it here so no one accidentally gives [Mr. Greer] money.” The complaint also alleged “Mr. Moon’s users spread Greer’s song across different sites.”

The court says the defendants waived any fair use defense by briefing it inadequately.

Knowledge of Infringement. “Mr. Greer’s takedown notices complied with 17 U.S.C. § 512(c)(3).” That’s great, but is it relevant? For unexplained reasons, it does not appear that the defendants are invoking the 512 defense. As a result, the opinion only discusses common law contributory infringement claims. But does a statutory notice satisfy the common law knowledge requirement? The court says it does–a logical and defensible conclusion. However, the court should have explained this more because 512(c)(3) expressly says that it only defines what constitutes disqualifying knowledge for purposes of the statutory safe harbor.

Material Contribution to Infringement. Failure to honor the 512(c)(3) notice would disqualify the defendants for 512. However, this isn’t a 512 case. Instead, the court remarkably says that failure to remove content in response to 512(c)(3) does not, without more, constitute a material contribution to third-party infringement. That is inconsistent with how I’ve taught the subject for 25+ years, so it would have been great for the court to defend this proposition more thoroughly.

Yet, at the same time, the court says that Greer adequately alleged the “more” sufficient to satisfy the common law “material contribution” element:

When Mr. Greer discovered the book had been copied and placed in a Google Drive on Kiwi Farms, he “sent Mr. Moon requests to have his book removed . . . .” Mr. Moon pointedly refused these requests. In fact, instead of honoring the requests, Mr. Moon posted his email exchange with Mr. Greer to Kiwi Farms, belittling Mr. Greer’s attempt to protect his copyrighted material without resort to litigation.

After the email request, Kiwi Farms users continued to upload audio recordings of Mr. Greer’s book, followed by digital copies of his song. When Mr. Greer discovered the song on Kiwi Farms, he sent Mr. Moon a takedown notice under the DMCA. Mr. Moon not only refused to follow the DMCA’s process for removal and protection of infringing copies, he “published [the] DMCA request onto [Kiwi Farms],” along with Mr. Greer’s “private contact information.” Mr. Moon then “emailed Greer . . . and derided him for using a template for his DMCA request” and confirmed “he would not be removing Greer’s copyrighted materials.” Following Mr. Moon’s mocking refusal to remove Mr. Greer’s book and his song, Kiwi Farms users “have continued to exploit Greer’s copyrighted material,” including two additional songs and a screenplay…

Mr. Greer’s complaint alleged Mr. Moon knew Kiwi Farms was an audience that had been infringing Mr. Greer’s copyrights and would happily continue to do so. Indeed, Kiwi Farms users had been uploading Mr. Greer’s copyrighted materials with the explicit goal of avoiding anyone “accidentally giv[ing] [Mr. Greer] money.” Further infringement followed—encouraged, and materially contributed to, by Mr. Moon.

So, what exactly is the “more” here beyond Moon’s failure to remove? The court says: “the reposting of the takedown notice, combined with the refusal to take down the infringing material, amounted to encouragement of Kiwi Farms users’ direct copyright infringement.”

Ugh. First, the common law contributory infringement elements refer to “induce, cause, or materially contribute” direct infringement, not “encourage.” The term “encourage” comes from the Grokster inducement test, but the court is very clear that it is applying the common law contributory infringement test, not the inducement test. So in its effort to accommodate a pro se complaint, the court conflated the two doctrines and messed up long-standing contributory copyright infringement principles.

Second, the court seems to be saying that Moon’s inaction was OK, but Moon’s inaction + posting the takedown notice is not OK. What? This suggests that all contributors to Lumen have exacerbated their legal risk by providing greater transparency into the shadowy world of copyright takedown notices. That cannot be the right legal standard, and I am reasonably confident no other court would reach that conclusion. Oy, what a mess.

As a result, the contributory copyright infringement claim is revived and remanded back to the district court.

Implications

This case contributes to the jurisprudence of the copyright exposure of web hosts for third party content when the DMCA online safe harbors are not available. The court’s holding that failing to remove known infringing items isn’t sufficient for contributory copyright infringement would be a huge win for defendants. However, because the defendants lost the ruling by reposting the takedown notice, the outcome is almost worse for defendants. I view this outcome as a situation where the court bent copyright’s legal rules to favor a pro se plaintiff and to punish Kiwi Farms for its mockery and harassment. That makes it dubious precedent on all points.

Because Kiwi Farms creates so many problems for its harassment victims and spurs regulators to call for reactive (over)regulation, I’m sure there is high interest in finding any legal doctrines that could shut it down. This ruling shows how copyright law could be a Kiwi Farms killer–no legal reform required. Yet, we should be careful celebrating copyright’s censorial powers. It might lead to a laudable consequence as applied to Kiwi Farms, but as Prof. Silbey and I have documented, copyright also allows for the widespread scrubbing of socially beneficial content. We definitely don’t want more copyright doctrines that facilitate pernicious removals.

Case citation: Greer v. Moon, 2023 WL 6804866 (10th Cir. Oct. 16, 2023)

BONUS UPDATE: Business Casual Holdings, LLC v. YouTube, LLC, 2023 WL 6842449 (2d Cir. Oct. 17, 2023). “Business Casual asserts that three videos posted by TVNovosti on the RT Arabic channel on YouTube contained copyrighted content.” The district court dismissed the complaint.

Contributory Infringement. The uploader allegedly took steps to conceal the infringement from YouTube. As a result, Business Casual didn’t allege YouTube had knowledge of the infringement before its takedown notices, at which point YouTube promptly removed the videos. Instead,. Business Casual argued that YouTube should have terminated the uploader’s account entirely, not just remove the infringing videos. However, the account didn’t infringe Business Casual’s copyrights further, so account termination wouldn’t have mattered.

Vicarious Infringement. “YouTube did not decline to exercise its right to stop TV-Novosti’s alleged infringement, and instead removed the three videos shortly after learning about their alleged infringement.” More evidence that vicarious and contributory infringement are collapsing into each other.

DMCA Repeat Infringer Policy. Business Casual claimed that YouTube foreclosed the 512 safe harbor because it didn’t follow its repeat infringer policy, an argument the court called “entirely misplaced.” The court resolved the case on the failure of the prima facie elements, so the court never reached YouTube’s DMCA defense. So, “there is no affirmative cause of action for any alleged failure by YouTube to apply its Repeat Infringer Policy in accordance with the DMCA’s safe harbor provisions.” This is why I teach my students to always run through the plaintiff’s prima facie case before turning to the defenses. If the prima facie case fails, the defenses are moot.

Pingback: Kiwi Farms ruling sets “dubious” copyright precedent, expert warns | Ars Technica()

Pingback: Links for Week of October 20, 2023 – Cyberlaw Central()