Background

Tech companies of every kind use graphic user interfaces (“GUI”) as a powerful differentiator of products, user experience, and branding. Companies are smart to leverage GUIs. It’s well known by marketing professionals that a well-implemented GUI can positively influence a purchaser’s decision to buy a particular product or service. By contrast, sales can be adversely affected by a boring, uninspiring GUI. Given the importance of GUIs, they can be a target for copycats. However, there are effective ways to protect intellectual property in GUIs and enforce that intellectual property against competitors who choose to infringe.

Over a hundred years ago, Congress created “design patents” to offer companies a way to protect the “ornamental” features of products. An ornamental feature is usually the exterior part or the part of the functional product that a consumer would see. For example, a GUI makes an otherwise complex piece of software look fun, easy, or joyful to a user. Design patents strike a fair balance in terms of IP protection versus cost. A design patent will not protect competitors from copying the technology “under the hood” like a novel algorithm. (This is the function of a utility patent.) Instead, a design patent will protect how the novel graphical user interface looks (not how it works).

Scope of Protection

The big question for many applicants for design patents is how broad the scope of the patent will be. An applicant for a design patent may be able to slice and dice a GUI into many parts and typically can apply to protect each of those independently. For example, a company can dissect its GUI down to the level of individual icons and choose to apply to protect any of these. On the other hand, companies may choose to broadly protect the entire GUI as it would look on a screen, or, on various different screens depending on how a user navigates the GUI.

As one would expect, each type of design patent protection has its own advantages and disadvantages. Intellectual property, whatever the type or kind, is only as good as its enforceability in court. To determine whether a competitor infringes a design patent on a GUI, courts will conduct a side-by-side comparison of the design patent and the allegedly infringing GUI (or portion of the GUI, such as the icon). Then, the court considers whether, in the eye of a consumer, the two designs are substantially the same to cause deceit and induce the consumer to purchase the non-patented product. This test is intuitive for a jury to understand—everyone has been a consumer and has compared different apps, products, software, etc.

Examples of Actual GUI Design Patents

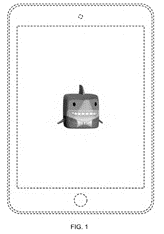

Next, we’ll look at a few examples of actual design patents and analyze the GUI features they protect. There are two very important rules when evaluating design patents: (1) the scope of the patent is defined by what is shown in the figures; and (2) only solid lines are part of the claimed design—the design aspects within dotted lines are not part of the claimed subject matter, but can provide helpful context for the court or jury during an infringement analysis.

U.S. Patent No. D875,785

“Display Screen with Icon”

The first example is an icon. The first figure shows what appears to be a cartoon shark in grayscale, as it would be pictured on a phone or tablet screen. The applicant intentionally dotted the screen, likely so that if ever enforced against a competitor, the patent would provide context to a judge or jury for an infringement analysis. However, the dotted portion is not part of the scope of the patent.

“Display Screen with Graphical User Interface”

U.S. Patent No. D743,414

The next example shows an image from a smartphone displaying the GUI. The smartphone portions at the top are dotted out and therefore not protected. The solid line portions of the design are the “Back” button, the icon of the Earth, and large box with the view of a building, and four remaining boxes at the bottom showing “love it,” “want it,” “have it,” and a box for comments. Accordingly, these seven solid line portions will constitute the claimed subject matter (notwithstanding the other figures in the design patent). From an infringement perspective, the design patent is agnostic as to the substantive content inside the large box, or any content under the “Back” button. However, the inventor apparently had a specific app in mind when drafting these figures given the level of detail in the dotted portions. Presumably, although not technically part of the claims, the dotted-out features could help the inventor show a side-by-side comparison of how the how a competitor may have copied the inventor’s specific app.

“Graphical User Interface for Portion of a Display Screen”

U.S. Patent No. D618,695

In this final example, the GUI appears to be for a graphing application. The protected, solid line features of the design patent include the outline of the line graph, a sample line, the x-axis with a “slider” button, and a triangle “play” button. The main unprotected features are the representations of the data in the graph, and the outline of the screen and the “play” button. Thus, the substantive “content” on the screen is mainly in dotted lines, while most of the interface itself is solid. This is similar to the previous example where the content was dotted out. This is a smart strategy, because if any of the content from the application is in solid lines, then an infringer could simply change that content and argue for non-infringement. For example, if the circles below were in solid lines, perhaps a competitor could have used star shapes, or hexagons, to depict the data. But, as issued, the patent protects against combinations such as this by leaving those easily changed portions dotted out.

Conclusion

Design patents are an effective way to protect a graphic user interface. Among other things, applicants for design patents have many options to choose from, including whether to patent any of the GUI icons, and whether to capture the GUI as a whole on a screen-by-screen basis. A difficult choice is what to keep in solid lines and what to “dot out”. The more an applicant dots out, the fewer GUI features will be subject to protection. On the other hand, the more an applicant uses solid lines, the more likely it is a competitor can design around certain solid line portions and escape infringement. There are other forms of intellectual property that can help fill in some of the gaps of design patent protection for GUI’s—watch for our forthcoming “Part 2” article on copyright protection for GUIs.