Ex parte Zhang, Reexam No. 90/014,234, 2021 WL 633718 (PTAB)

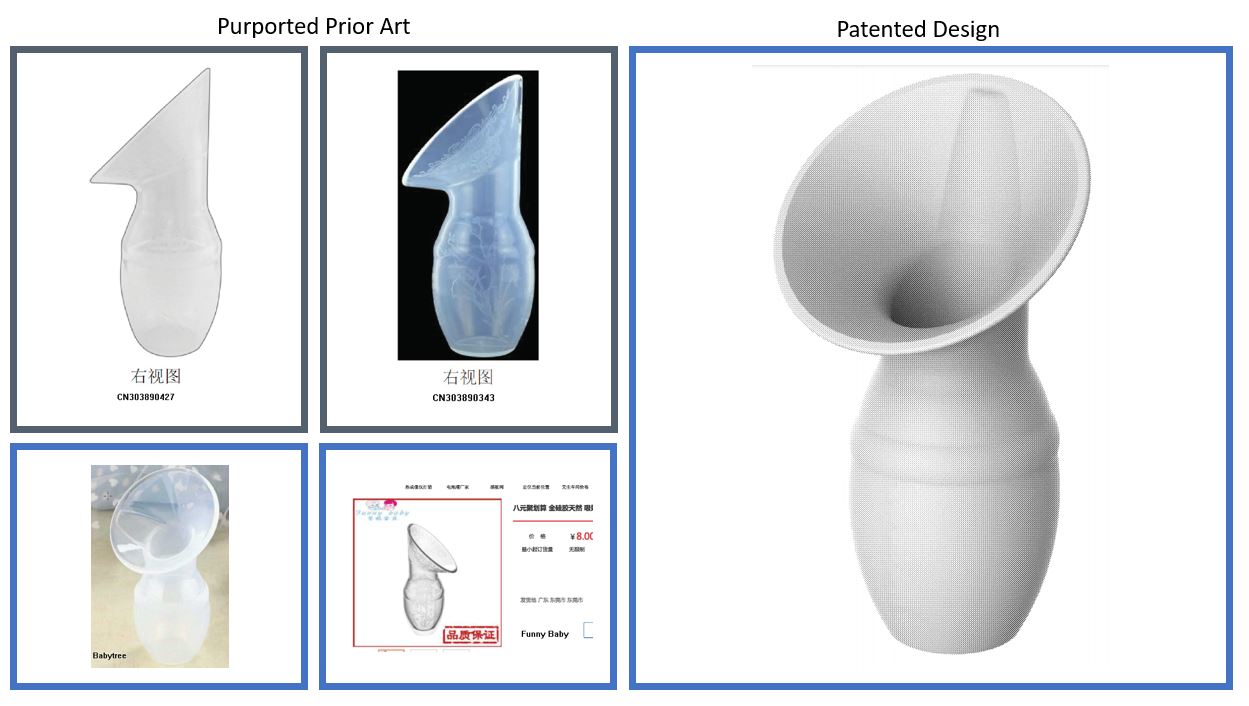

Folks continue to file anonymous ex parte reexaminations. Michael Piper of Conley Rose filed this one on behalf of an anonymous party challenging Zhang’s U.S. Design Patent No. D810,925 (“breast pump”). The reexamination examiner agreed with the challenge and issued a final rejection that the claimed design was anticipated by four different prior art references. Note that design patent anticipation asks whether the design to be patented is “substantially the same” as the prior art in the eyes of an ordinary observer.

Two designs are substantially the same if their resemblance is deceptive to the extent that it would induce an ordinary observer, giving such attention as a purchaser usually gives, to purchase an article having one design supposing it to be the other.

Door-Master Corp. v. Yorktowne Inc., 256 F.3d 1308 (Fed. Cir. 2001) (citing Gorham Co. v. White, 81 U.S. 511 (1871)).

Not Prior Art: On appeal, the PTAB has reversed — finding that cited references are not prior art at all.

First to Disclose: Two of the references were Chinese Design Registrations filed and published a couple of months before Zhang’s filing date. Prior to that date, but still within one-year, Zhang had already licensed the design and licensed pumps embodying the patented design were on sale in China. The timing of this prior public disclosure was just right to save the day under Section 102(b)(1)(B).

(b)(1) A disclosure made 1 year or less before the effective filing date of a claimed invention shall not be prior art to the claimed invention under subsection (a)(1) if—(B) the subject matter disclosed had, before such disclosure, been publicly disclosed by the inventor … or another who obtained the subject matter disclosed directly or indirectly from the inventor or a joint inventor.

Zhang apparently did not make this argument until the appeal, and, the examiner withdrew his rejection after receiving the declaration with supporting evidence.

The other two references were internet publications purportedly published online two-years before Zhang’s application filing date. However, the PTAB found insufficient evidence proving their publication dates.

Here, an anonymous third party, through counsel, provided the USPTO with copies of two webpages in a foreign language … each paired with an uncertified English translation. Both documents and translations were submitted by a third party requester in a very unclear, grainy or pixelated manner and the text and details over the figures are very difficult to discern.

The submitted material do include printed dates, but the PTAB found them unclear and insufficient without any corroborating evidence regarding context or accuracy. Further, no evidence was submitted showing that the sites were publicly accessible as of those dates, and the pages are no longer available on the internet.

There is simply no explanation or verification of the source, date or accessibility of the information presented on these documents. While we can put some weight in the duty of a signatory of a registered patent attorney in accordance with 37 C.F.R. § 11.18 that statements of fact are “believed to be true,” we simply cannot find the evidence sufficient to establish the documents as prior art.

Zhang. Thus, the PTAB reversed the rejection.

If the material from the third party that the PTAB discounted/dismissed turns out to be actual prior art, then are all bets off? It’s also not clear (no pun) whether the patentee received a copy of a clear/legible copy of the materials from the third party – service on the patentee is required under he rules. If the patentee had a clear/legible copy, how will the apparent inaction by the patentee following the PTAB decision be viewed if a dispute lands in court? That’s aside from speculation over whether the patentee knew the protestor and/or source of the material submitted.

“Both documents and translations were submitted by a third party requester in a very unclear, grainy or pixelated manner and the text and details over the figures are very difficult to discern.”

I wonder if EFS did this. I have submitted perfectly clear drawings and NPLs, only to have EFS butcher them into pixelated messes well after I submitted the filings (my downloads of the submitted docs at the time of filing were fine, but copies downloaded later were butchered). (I am probably doing something wrong in my PDF settings.) It is really unfortunate to have this at least partially impact the outcome of a proceeding that probably had some merit to it.

By the way, check out the reexam prosecution on PAIR. The Office Action was not issued from the CRU (possibly because there’s not enough volume to support a full time Design expert examiner in the CRU), and the Primary who signed off on it had two other Primary Examiners from two different art units as “conferees”. There was no reply filed in response to the Non-Final Office Action and so a Final Office Action was mailed. The patentee did respond to the Final, and received the customary Advisory Action. Appeal followed shortly thereafter. Given the intransigence demonstrated by the Examiner in the Advisory Action, it’s hard to say if filing a response to the initial Non-Final would have made any difference in this particular case, but failing to respond to the initial Office Action set a poor tone.

As noted at 1 below, a reexamination is ex parte [35 USC 305], with no way for the adverse requester to participate or respond or correct or add to its own initial input. Further, 35 USC 306 provides for only the patent owner to be able to appeal.

There used to be inter partes reexamination but it was eliminated, and rightfully so. It was a horrendously flawed process. The 3rd Party requestor had a right to submit comments after the patent owner responded to the Office Action but the patent owner did not have the ability to file a reply to the 3rd Party’s comments. Instead, if the comments went beyond the allowed scope, the patent owner had to file a petition to strike the 3rd Party’s comments. It was a mess as it gave the 3rd Party the ability to abuse the process and impermissibly inject comments that were not within the scope of what they were allowed to comment on.

An anonymous party willing to shell out the dough on an ex parte reexam and pay for a BigLaw Partner to prepare and file the reexam isn’t as anonymous as they’d like to think. The patentee usually has a good idea who ‘anonymous’ is and sometimes all it takes is a little research. I’ve dealt with US Third Party Submissions during examination, Post-Grant EPO Oppositions, and each time my client was pretty sure who the real party was.

Had the same thought ipguy. I’ll bet Zhang knows who the requester was.

Anyone know why the Office keeps requesters secret? Isn’t it good public policy for patent owners and the public to know who the challenger is?

I wonder if that is different than what is required for Article III courts (as much as Paul likes to cheerlead the IPR mechanism, he seems to have been awfully quiet about this apparent – and marked – difference)

The reason why it is useful and necessary to know the challenger’s identity in a civil trial or an IPR is that res judicata or collateral estoppel is liable to attach from such a process, so it must be known who is estopped in view of the proceedings. Because the petitioner in an ex parte re-exam does not participate, the “full and fair opportunity to litigate” prong of the test for either res judicata or collateral estoppel will never be satisfied for an ex parte petitioner. Therefore, no useful purpose is served by making the petitioner’s identity known.

Good civil trial / IPR distinctions / points Greg.

Yet, shouldn’t a patent owner be entitled to know who’s trying to take away their patent from them?

What’s the thinking / (supposed) reason behind keeping it a secret?

Not to speak for Greg (who may have other reasons or may confirm this one), but one known aspect of the AIA in the decisions by Congress to create a system with a bi-furcated fora was to enable ANYONE to challenge a patent in the Step 1 proceedings, without regard to any actual Article III standing (and the points provided by Greg related to such Article III standing).

Through the AIA, it was the will of Congress to establish a free-for-all for taking shots at granted patents.

In such a view, the “who” simply does not matter. When Congress indicated “anyone” they indicated this sense of “the identity does not matter.”

Sure, the patent holder comes out on the short end of that stick — especially given that one of the sticks in the bundle of property rights is taken at the institution decision point (regardless of any noon-Article III ‘adjudication’), and that this legislative taking is made with ZERO recompense of that valuable stick (as to value, just ask i4i).

This is one major reason why the Oil States case was wrongly decided.

[S]houldn’t a patent owner be entitled to know who’s trying to take away their patent from them?

I have no strong opinion on this point one way or the other. I suppose that one could make an argument either way. It is more a matter of taste (rather than objective public policy analysis) how one might decide between those arguments.

What, no Web Archive (Wayback Machine)…?

The AIA Section 102(b)(1)(B) “exception” to normal AIA 102 and 103 limitations to filing dates [the AIA residue of a U.S. “grace period”] can easily be unanticipated, as here, for prior art less than a year older.

Because a reexamination is entirely ex parte, there is no way for the adverse requester to rebut any patent attorney argument, or correct or add to its own initial input for any reason. Even if the patent owner raises correctable document authentication or other technical errors. But of course IPRs cannot be anonymous. [That anonymity may not be that beneficial if the patent owner has sued someone for infringement or otherwise knows the competitor most likely to be threatening its patent.]

Also, in general, full anticipation challenges are more difficult, so that an alternative challenge under 103 is often desirable, although it would not have helped with this evidentiary decision.

Comments are closed.