We are pleased to bring you a guest post from Kartik Sharma and Aditya Singh on the recent decision by the Calcutta HC regarding the infringement of AMUL’s trademark. Kartik and Aditya are 2nd year students at NLSIU, Bengaluru.

‘AMUL’ Trademark Row: Scrutinizing Cal HC’s Ruling on Infringement

Kartik Sharma & Aditya Singh

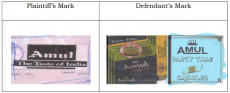

On September 1, 2022, the Calcutta HC, in Kaira District Cooperative Milk Producers Union Ltd v. Maa Tara Trading Co (‘AMUL’), held a non-competitor liable for infringement of a trademark. The facts, in brief, are that a famous cake shop in Kolkata was found giving away complimentary candles packaged in a box with a logo similar to that of the well-known brand ‘AMUL’. The plaintiff then filed a suit seeking a decree of injunction against the defendants for infringement of trademark (TI), which was granted by the court.

The case is relevant as the court reached a conclusion on infringement without an examination of the relevant law on infringement by non-competitors, covered by Section 29(4) of the Trademarks Act, 1999. This post evaluates the court’s reasoning and contrasts it with the requisite threshold for a finding of infringement u/s. 29(4) of the Act.

The plaintiffs (Kaira District Cooperative Milk Producers Union) had filed a suit for perpetual injunction based on TI along with a claim of passing off in an ex-parte proceeding. The court began its inquiry with the first ingredient of s. 29(4)(a) i.e., is to discern a similarity between the impugned and the registered trademark. This is in line with the statutory threshold and various tests laid in precedent cases, hence the same is not subject to analysis in this paper. Sub-clause (b) of s. 29(4) which requires the goods to be of non-similar nature is also prima facie satisfied. However, the water starts getting muddy when the court, instead of continuing to sub-clause (c), jumps directly to the test of ‘passing off’ to establish TI.

One of the causes of action against the defendants in AMUL was the tort of passing off (‘PO’). As explicated by the court, PO is not contingent on registration. The major problem that arises is that there are variations in the test of passing off. For example, the Calcutta HC went with the tests laid down in Cadila Healthcare Ltd. v. Cadila Pharmaceuticals and A.G. Spalding v. A W Gamage. The test formulated in the former mainly looks at the context in which the mark has been used and does not pertain to its effects either on the senior or the junior.

However, the primary elements needed to establish passing off as laid down in Reckitt & Colman Products Ltd. v. Borden Inc. are three in number: goodwill or reputation of the plaintiff’s goods; misrepresentation by defendant leading or likely to cause people to believe that the goods are in fact that of plaintiff; plaintiff has suffered or is likely to suffer damage as a consequence.

We submit that the threshold for PO is lower compared to that of TI under s. 29(4) and this is where the court faltered when it moved to applying the test of passing off but did not satisfy the threshold laid down in s. 29(4) (c) for TI. This is to say that while TI and passing off were 2 separate claims, the court ended up using the test of passing off to evaluate TI.

A cursory glance at s. 29(4)(c) highlights the need to demonstrate unfair advantage being gained by the violator or detrimental impact on the distinct character or reputation of the trademark. This stipulation of actuality of consequences is in contrast to the probability-based perspective employed in a PO action. On a purely logical basis, likelihood of damage is a less rigorous standard compared to evidence of actual detriment or unfair advantage. The next section shall uncover the eliding over of s.29(4)(c) in the court’s analysis and how it founded the existence of TI on the elements of PO.

Missing Component

The court in ITC Ltd. v. Philip Morris Products had observed how there is a need to establish all the constitutive elements of s. 29(4) to make out a case for TI. No presumption of infringement exists in the application of s. 29(4) and a judicial scrutiny entailing a cumulative assessment of facts and evidence is to be undertaken. This article now analyses each constitutive condition of s. 29(4)(c) and the requisite rigor of enquiry. On an examination of the doctrinal standards and past rulings, the glaring omissions on part of the court would become clear. In a nutshell, the court didn’t apply sub-clause (c) at all.

‘Detrimental to’

One of the grounds of TI is the detrimental impact of the impugned mark on the reputation or the distinctiveness of the trademark. The former act is called tarnishing and the latter, blurring. Tarnishing occurs when the ‘ability of the mark to stimulate the desire to buy those goods is impaired’. This would mean that the impugned mark must be suggestive of a product with negative correlation to quality, only then would the use of the mark harm the reputation of the registered trademark. Tarnishing is a difficult legal ground to evaluate and founding it in speculative harm is not a tenable idea. The court here seems to have taken a logical leap and concluded the future/speculative harm to AMUL’s reputation. It did not evaluate the position and status of the defendants in their domain and of their products. Apart from this, it is also imperative to gauge the possibility of confusion for there to be tarnishment or blurring hence, while TI also extends to dissimilar goods, the sectors must not be so materially different that there cannot be a possibility of confusion as the fact that the senior company is working in the sector of junior company cannot be contemplated by the consumers.

‘Unfair Advantage’

In addition to ‘tarnishment’ or ‘dilution’, s. 29(4) provides for ‘unfair advantage’ as another ground for TI. To understand how the same has been interpreted, L’Oreal v. Bellure is a pertinent case to explore. In L’Oreal, the court construed unfair advantage as free-riding which essentially means that the junior is unduly benefiting from the goodwill and investment of the senior’s brand. While this interpretation has been subject to various criticisms for being over-expansive and its other drawbacks such as its detrimental effects on competitiveness, that is not a part of this paper’s analysis. Even if we stick to CJEU’s reasoning in L’Oreal, Bellure was held to be a free rider as it was observed that they were able to charge higher prices due to their product’s similarity with L’Oreal’s perfumes. Hence, even in this case, there is a requirement to establish a direct advantage being reaped as opposed to just a mere possibility. This threshold became even higher in India after the Raymond Ltd. v. Raymond Pharmaceuticals wherein the court held that the gain has to be substantial and not just de minimus. Looking at the instant case of AMUL, the usage of AMUL would largely be immaterial considering the distribution by the manufacturers was B2B and complimentary to the consumers. There was no evidence to demonstrate any substantial profit gained by the defendant out of the TI.

As opposed to the test of ‘passing off’ which mainly centers around usage of the mark, s. 29(4) requires the plaintiff to either establish direct and substantial harm to the goodwill of the TM or an undue benefit gained by the junior of that degree.

‘Without due-cause’

As exhibited in this piece, there is a solid and distinct threshold to establish TI in s. 29(4). Further it cannot be said that they are weakened by the exception of ‘due cause’ available in the provision.

The threshold to avail the exemption of ‘due cause’ is high as well. This is to convey that the whole provision has been structured in a manner to preserve a particular standard of TI and it would not be correct to dwell into the application of ‘passing off’ and discarding this. To look at the English counterpart of s. 29(4) i.e., s. 10(3) of Trademarks Act, 1994, there is a requirement to show absolute and unavoidable compulsion of usage to invoke ‘due cause’. To investigate the jurisprudence in India, one pertinent case is that of Nestle India Limited v. Mood Hospitality. In this case, while the court does not lay down an elaborate objective test, it stipulates that there be a ‘tenable explanation’ for the usage. In its analysis of the facts, the court held that the mark was not used as a TM but as it was just a part of the name of a specific product still under Maggi’s branding. Apart from that the word ‘Yo!’, the usage of which was contended as TI is a generic word, put in place to market the product to younger consumers. Hence, it is hard to avail ‘due cause’ exception for the usage of a unique TM not in use in general parlance. Another relevant factor of this case was also that even the junior user i.e. Nestle, itself, has a very distinct reputation. The Calcutta HC failed at doing a similar factual examination and excavating possible reasons, if any, for the infringement.

Conclusion

The foregoing examination reveals how the court failed to employ a robust application of s. 29 by glossing over sub-clause (c). The court seemed to have taken the fulfillment of ‘passing off’ as enough to constitute a case for TI. We have already pointed out how the doctrinal rigour of TI is higher compared to passing off. Such lowering of threshold, while a higher one has been set by a statute, prevents the assessment of effects of the TM’s usage i.e., was there a negative network externality being created for the senior or was the junior getting a boost from positive externality effect. Holding TI without the presence of these causes also has an unjustified adverse impact on the competition which is something the courts need to be cautious about. This issue of insufficient analysis has also been seen in cases such as TATA Sons v. A.K. Chaudhary which in turn is antithetical to the objective of the statute.

I am very new to the subject, so pardon me if this doubt is stupid. Shouldn’t passing off be more difficult to prove than trademark infringement? PI action is instituted in case of unregistered TM. So wouldn’t it make sense to make PI harder to prove than TM infringement?

Hola Novice,

Thanks for raising this question!

Yes, I think you are correct. Theoretically, the threshold is higher in passing off because the first thing to be proven here is ‘goodwill’ which is not so easy to prove. However, based on my observation and research, the Courts nowadays don’t pay (much) attention on this part and grant passing off remedy merely by looking at the similarity in the marks.Needless to say, my claim needs empirical backing.

Another interesting thing to note here is that there is a difference between goodwill and reputation, though both are nowadays used interchangeably. A similar confusion can be also be observed around the terms “well-known mark” and “mark with reputation”. Recent courts have also highlighted the difference between the both, but they are work looking into/point out.

Best

A SpicyIP Reader

Very intuitive read. Interesting how only second years can write so well. These kids have a very bright future