by Dennis Crouch

Mondis Tech. LTD v. LG Electronics (Fed. Cir. 2021)

This is an appellate procedure case focused on the timing of the notice of appeal. The statute creates a hard 30-day deadline for filing a Notice of Appeal (NOA). 28 U.S.C. § 2107(a). One difficulty though is that the statutory scheme muddies the water in terms of when to start counting. The courts have previously figured out how it works for ordinary appeals — you get 30-days from the final judgment. But, there is a special statute that allows interlocutory appeals in patent infringement lawsuits that creates a right to appeal in cases that are “final except for an accounting.” 28 U.S.C. § 1292(c). With that provision, it would seem that the notice of appeal should be filed within 30 days of the court action that triggers the final-except-for-an-accounting status. But, there is another level of complication that comes from the NOA tolling provision found in Fed. R. App. Proc. 4(a)(4). Rule 4(a)(4) focuses on post-verdict situation where a party files several motions for Judgment as a Matter of Law (JMOL) or New Trial. In that situation, the Rule states that “the time to file an appeal runs … from the entry of the order disposing of the last such remaining motion.” Rule 4(a) then goes on to particularly state that the notice of appeal is due 30 days after the last JMOL/NewTrial motion is decided.

The holding here: The court read an exception into Rule 4(a) — finding that it does not apply to § 1292(c) interlocutory appeals. As such, the appeal here was untimely and therefore dismissed for lack of jurisdiction.

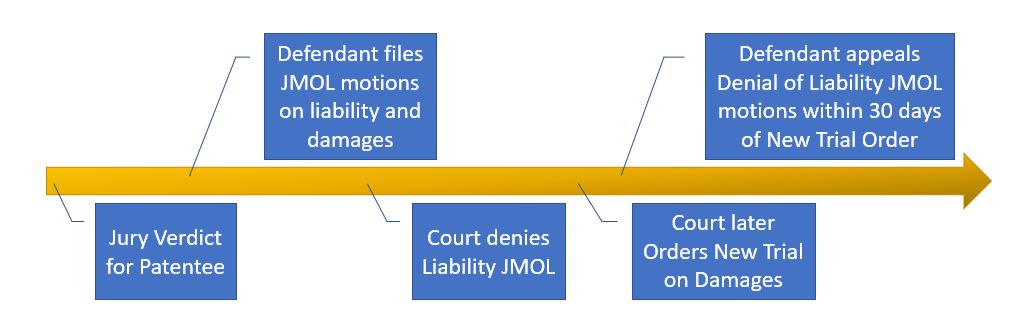

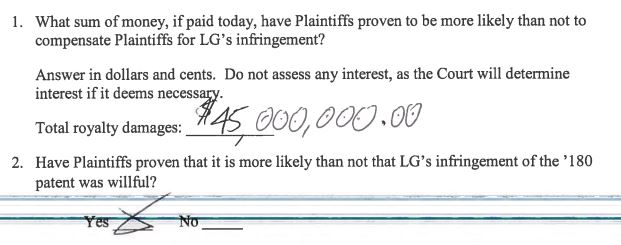

Lets back up: At the trial court, a jury with the patentee and concluded that LG was willfully infringing the Mondis/Hitachi U.S. Patent No. 7,475,180. Post-verdict, the district court denied LG’s motions for JMOL on infringement and validity and then later granted a new trial on damages and willfulness.

Normally, a new trial delays appeal because the case is not yet final — and so no immediate appeal under the Final Judgment Rule. 28 U.S.C. § 1291. The statute also provides for interlocutory appeal in this particular situation — patent infringement lawsuits that are “final except for an accounting.” 28 U.S.C. § 1292(c). In Robert Bosch, LLC v. Pylon Mfg. Corp., 719 F.3d 1305, (Fed. Cir. 2013), an en banc Federal Circuit held that “an ‘accounting’ in the context of § 1292(c)(2) includes the determination of damages.”

So, LG had a right to appeal once the renewed JMOL motions on liability were denied. But, LG did not appeal until months later, after the new trial on damages was ordered. As mentioned above, FRAP 4 typically tolls appeals until all post-verdict motions are decided. Here, the court held that the rule does not fully apply in the 1292(c) interlocutory appeal situation — but rather only tolls the timing of the interlocutory appeal until all liability-related motions are decided.

When only motions unrelated to the judgment being appealed remain, the judgment is final except for an accounting and the time to file an interlocutory appeal begins.

Because FRAP 4(a)(4) does not toll the interlocutory appeal period for outstanding motions unrelated to the interlocutory judgment, the damages motions that remained outstanding after the September Order did not toll the time frame for LG to file its notice of appeal on the liability portion of this case. . . . Because LG did not file its notice of appeal within thirty days of the issuance of the September Order, its notice of interlocutory appeal was untimely.

Slip Op. The court notes that this interlocutory appeal process is optional. LG will still be able to appeal all of the issues once the damages/willfulness trial is completed.

Hmm, no interest for this one so far it seems. The court’s bottom-line decision makes sense just as a matter of pure logic I guess. A pending post-trial motion on damages, which is considered an aspect of an “accounting”, obviously can’t affect the finality of the liability judgment once any post-trial motions on liability are resolved.

But the court’s reasoning is sort of obscure and it lacks much in the way of case-law or statutory/rule-based authority. On the latter aspect, authority, it only cites two cases. And just one of those, Budinich, is discussed at length. However, Budinich doesn’t even address the main issue of the interplay between the statutes and the rules. The remaining case, Lane, isn’t really on point either.

Following that, we get to reasoning. I guess I take issue with two main aspects: (1) the construction of FRAP 4 and (2) the suggestion that reading the Rule in the way LG proposes would somehow “conflict” with the statutes. As for (1), it seems like the court is insisting on reading a “relatedness” requirement (between the post-trial motion and the judgment being appealed) into the Rule that just isn’t there. The Rule says pretty clearly the time is tolled (or doesn’t commence, which I think is technically a little different from tolling) until the “last” motion is resolved. And it doesn’t distinguish between motions that are “related” to the judgment or not. If you start imposing a “relatedness” requirement, then all of a sudden you can have multiple “last” motions depending on which judgment they “relate” to, but that doesn’t make sense. So it’s hard to fault LG for reading the Rule the way they did.

As for (2), I don’t see any “conflict” between the Rule and the statutes at issue, specifically § 1292. Section 1292 just indicates which kinds of interlocutory decisions can be appealed, including ones like here that are final except for an accounting. But the appealability itself isn’t disputed, just the timing for noticing the appeal. So maybe the court meant to say there was a conflict with § 2107 instead. In that case though, it seems like FRAP 4 violates § 2107 in every possible instance. Section 2107 says the time for an appeal is within 30 days from entry of judgment, and the only exceptions it permits are within that same statute. It says nothing about any exceptions beyond the statute, including exceptions provided by rules. So wouldn’t every application of FRAP 4 to “toll” the appeals period in every instance—whether for a normal final judgment or for an interlocutory decision like here—contradict the statute? I don’t know, but according to the court’s logic it seems like it would.

The approach LG proposes also seems a lot easier to administer. When multiple post-trial motions are flying around, instead of needing to monitor which motion “relates” to which judgment or aspect of the judgment, you just file your NoA whenever the very last motion is resolved. I think there’s something to be said for that approach compared to what the court would insist on.

Hopefully this case will catch the attention of Bryan Lammon over at Final Decisions and he can weigh in with actual expertise instead of my amateur pontificating!

I forgot to mention one more thing. It does seem like LG could have acted a bit more conservatively in filing its NoA. FRAP 4(a)(4)(B)(i) provides that a prematurely-filed NoA nonetheless “becomes effective … when the order disposing of the last such remaining motion [i.e., those specified in 4(a)(4)(A)] is entered.” So had LG filed as soon as the liability JMOL was denied, it would have been protected either way. If LG’s argument about “last” actually meaning “last” had carried the day, then, although filing before the damages new trial motion would be premature, 4(a)(4)(B)(i) would still kick in to make the NoA effective once that motion had been resolved. And under the court’s theory, then the NoA would be timely in the first instance because was properly filed after disposition of the “related” post-trial motion. On that note, it’s a bit odd for the court not to have mentioned 4(a)(4)(B)(i) at all in the decision.

Comments are closed.