“Respondents breached a provision that bars reproduction, distribution, and so forth for ‘commercial purposes.’ And Respondents, highly sophisticated competitors, do not dispute they knew they had promised not to do those things and did them anyway.” – Genius Reply Brief

The U.S. Supreme Court today invited the Solicitor General’s views in a copyright case that asks the High Court to grant a petition on the question of whether the Copyright Act’s preemption clause allows a business “to invoke traditional state-law contract remedies to enforce a promise not to copy and use its content?”

The U.S. Supreme Court today invited the Solicitor General’s views in a copyright case that asks the High Court to grant a petition on the question of whether the Copyright Act’s preemption clause allows a business “to invoke traditional state-law contract remedies to enforce a promise not to copy and use its content?”

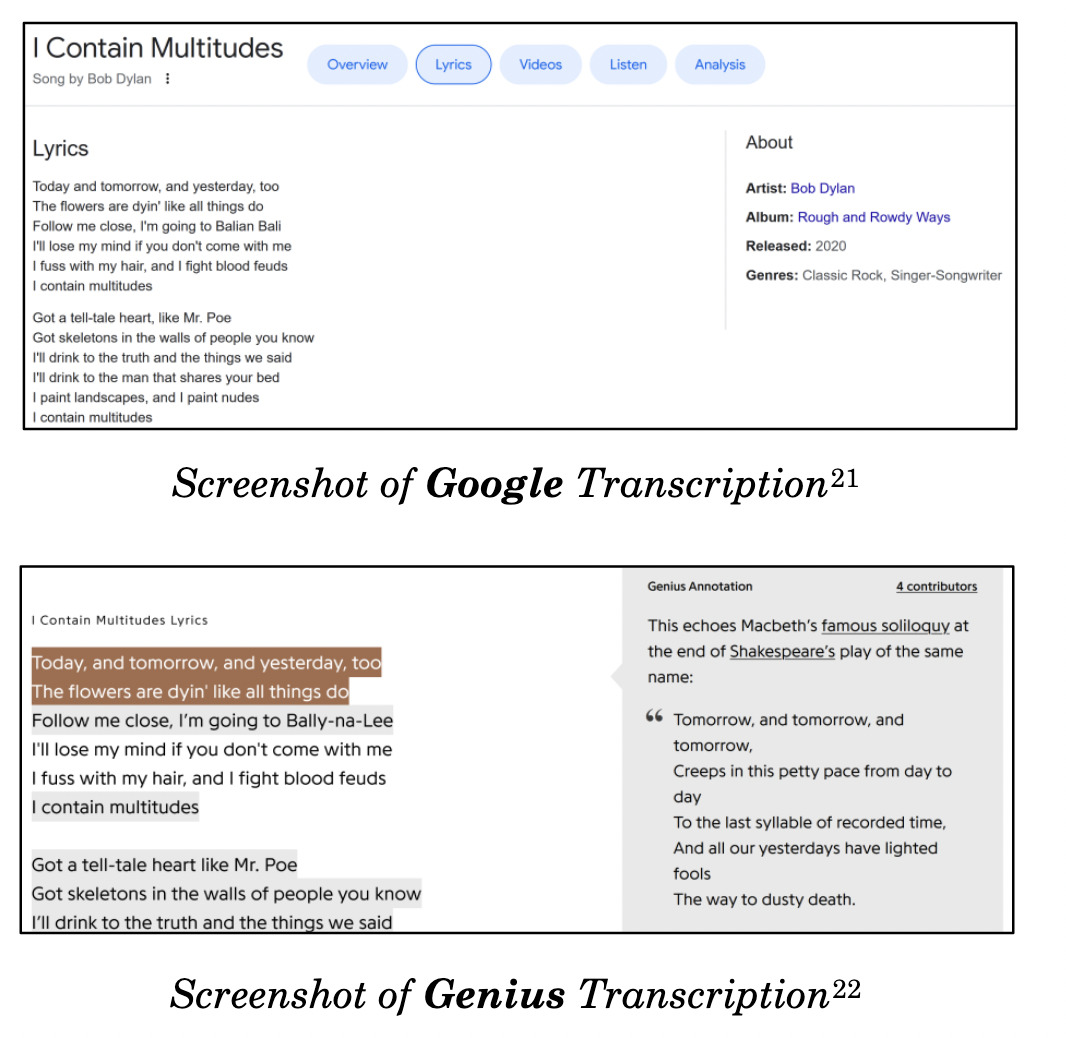

The petition was brought by ML Genius Holdings (Genius), an online platform for transcribing and annotating song lyrics, against Google and LyricFind, which Genius claims breached its website Terms of Service by “stealing Genius’s work and placing the lyrics on its own competing site, drastically decreasing web traffic to Genius as a result.”

Whose Rights?

In March 2022, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit upheld a district court’s dismissal of Genius’s breach of contract and unfair competition claims as statutorily preempted by the Copyright Act under 17 U.S.C. § 301. Genius subsequently petitioned the Supreme Court in August, arguing that the Court should review the case because “[t]he circuits are intractably split” on the Copyright Act’s preemption of breach-of-contract claims. Genius explained in its petition that the Fifth, Seventh, Eighth, Eleventh, and Federal Circuits follow the rule that breach-of-contract claims are not preempted, but the Sixth and now the Second Circuits have “expressly departed from this majority rule.”

In their Brief in Opposition to the petition, Google and LyricFind argued that Genius attempted to “invent new rights” by ignoring the true copyright owners of the lyrics and granting itself “copyright-equivalent” rights via its Terms of Service, even though Google and LyricFind hold licenses from the real copyright owners to reproduce and display the lyrics.

But Genius countered in its November 18 reply that Google is purposely misrepresenting the petition and Genius’s arguments by accusing it of hiding its terms of service and granting itself copyright-equivalent rights that would make every anonymous visitor to the site vulnerable to a lawsuit. Genius’s reply explained:

“Respondents breached a provision that bars reproduction, distribution, and so forth for ‘commercial purposes.’ And Respondents, highly sophisticated competitors, do not dispute they knew they had promised not to do those things and did them anyway—caught red-handed after Genius asked them to stop. So, Genius’s complaint does not seek exclusive rights against some random music superfan.”

Amici Support

Two amici have also weighed in thus far in support of Genius’s petition. The Open Markets Institute urged the Supreme Court to grant the petition because “the Second Circuit approach provides companies like Google with a license to scrape third-party websites and misappropriate the economic benefit of their work product, even after expressly agreeing not to do so as a condition of accessing that work product.” The brief added that Google’s conduct constitutes a type of “unfair competitive behavior” that will only intensify if the Second Circuit’s decision is allowed to stand.

From the Digital Justice Foundation amicus brief

The Digital Justice Foundation argued that Genius provides a public service via its crowdsourced annotations of song lyrics, which shed historical and cultural light on the artists and songs, and that Google’s rampant scraping of Genius’s content disincentivizes users from annotating the lyrics. The brief explained:

“Imagine a museum organizes a collection of paintings, verifying each painting’s authenticity and creating plaques that explain each painting’s historical, cultural, and artistic context. The museum allows the public to view the paintings for free on the condition that visitors take no photos—a term-of-use printed on each free ticket. Nevertheless, a shopping mall sends an intermediary to photograph all the paintings and then displays the photos in a gallery that draws traffic from the museum. The mall does not provide any plaques or context for the photos, nor any attribution to the original museum.

That is the true big picture of this case.”

The Digital Justice Foundation also said the Second Circuit’s decision threatens “millions of other digital licenses that rely on innovative terms-of-use to govern the use of copyrighted artistic works” and that the question presented not only divides the Circuits, but “matters to the future of the Internet.”

The Court’s invitation for the SG to submit views may indicate it is considering granting the petition.

Image Source: Deposit Photos

Image ID: 118290464

Author: alexlmx

![[IPWatchdog Logo]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/themes/IPWatchdog%20-%202023/assets/images/temp/logo-small@2x.png)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/Patent-Litigation-Masters-2024-sidebar-early-bird-ends-Apr-21-last-chance-700x500-1.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/WEBINAR-336-x-280-px.png)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/2021-Patent-Practice-on-Demand-recorded-Feb-2021-336-x-280.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/Ad-4-The-Invent-Patent-System™.png)

Join the Discussion

2 comments so far.

Anon

December 13, 2022 10:34 amTerms of Service (and other “shrinkwrap” style) contract terms may well be viewed as contracts of adhesion.

I would also fold into any dialogue on the topic the Fake “license” agreements that do no more than attempt to defeat sales exhaustion.

Pro Say

December 12, 2022 07:49 pmWhat?! Google stealing the IP of another!?

Say it ain’t so, Joe! Say it ain’t so!

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Say_it_ain%27t_so,_Joe_