by Dennis Crouch

In 2022, the Federal Circuit held that an invention is only eligible for a US patent if a human conceived of the invention. Thus, no patents for invention wholly conceived by artificial intelligence. Thaler v. Vidal, 43 F.4th 1207 (Fed. Cir. 2022). Thaler’s petition for writ of certiorari to the US Supreme Court would have been due last week, but Thaler was able to obtain an extension with the petition now being due March 19, 2023. Thaler’s main attorney throughout this process has been Professor Ryan Abbott. The team recently added appellate attorney and Supreme Court expert Mark Davies to the team, and so it should be a great filing when it comes. The motion for extension explains that the case presents a fundamental question of how the law of inventorship should apply “to new technological methods of invention.”

Specifically, this case arises from the Federal Circuit’s denial of a patent to an invention created by an artificial intelligence (AI) system, holding that an AI system is categorically unable to meet the definition of “inventor” under the Patent Act. The questions presented in Dr. Thaler’s petition will have a significant impact on Congress’s carefully balanced scheme for protecting the public interest in promoting innovation and ensuring the United States’ continued international leadership in the protection of intellectual property.

Extension Motion. Part of the justification for delay is that Dr. Thaler and his attorneys have a parallel copyright case pending. Thaler attempted to register a copyright for a computer-created work of art. But, the copyright office refused once Thaler expressly stated that there was no human author. Thaler then sued in DC District Court. Most recently, Thaler moved for summary judgment, presenting the following question for the district court to decide:

With the facts not in dispute, this case boils down to one novel legal question: Can someone register a copyright in a creative work made by an artificial intelligence? The plain language and purpose of the Copyright Act agree that such works should be copyrightable. In addition, standard property law principles of ownership, as well as the work-for-hire doctrine, apply to make Plaintiff Dr. Stephen Thaler the copyright’s owner.

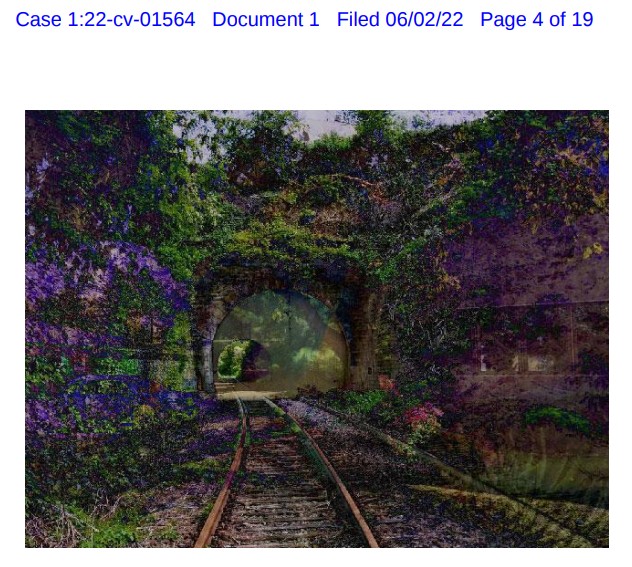

THALER v. PERLMUTTER et al, Docket No. 1:22-cv-01564, Paper No. 16 (D.D.C. Jan 10, 2023). The image, reproduced below from the complaint is known as “A Recent Entrance to Paradise.” (Registration Application #1-7100387071).

In another recent example, the Copyright Office has also canceled copyright registration for Zarya of the Dawn, apparently because of its AI-created status.

An actual law professor, albeit one from one of the most mentally (and morally) challenged states in the country: “ The team recently added appellate attorney and Supreme Court expert Mark Davies to the team, and so it should be a great filing when it comes.”

Sure, it’ll be a “great filing” because Dennis’ gets a little shock up his leg every time he hears certain names. Never mind the underlying facts or the result being sought. Mmmm, what a filing.

MM bro,

Can you tell me just 1-10 how HARD this PHONK is?

link to youtube.com

OT, but I am so sick of 36xx 101 rejections.

The conversations with examiners is just ridiculous. There is no correspondence with physical reality. Basically, the 101 is removed if the examiner can get the SPEs to agree to remove the 101. And the removal makes no sense.

Recently, I’ve had two removed and lost in two others.

Conversations with examiners are oftentimes ridiculous to begin with. What gets me is the inconsistency.

Examiner 1 says “add X” and that will get your around 101. I add X and I get an allowance. In a claim with Examiner 2, I add X to get around a 101 rejection, but the Examiner says that X isn’t enough and that I need to “add Y.” The same happens with Examiner 3 and Examiner 4.

There just isn’t any consistency. Then again, the Federal Circuit’s case law is inconsistent/poorly written. I know how to avoid 112. I know how to avoid 102/103 when I have the prior art in front of me. However, no one can say for certain how to overcome 101. As a result, we are all shooting in the dark — hoping to hit something.

+1

All that. But it is also just the language of 101 where the examiners say things like: “that could be performed in someone’s head”, “that is abstract”, “that is too broad”, “special purpose hardware”, “something more”, “advantages”, and so forth.

Most of the phrases are contrary to science and/or patent law.

You should document that and submit it in a direct challenge to the PTO as a bureaucracy in some form. APA case maybe. Arbitrary and capricious agency action, if you really believe it to be so. And be sure that the context is reasonably the same. All features are not the same in all claims as you know I’m sure.

You all reap what you sew. Imagine spending years to become registered, only to find the USPTO owns both sides of your license, and you just complain. Remember John DOLL? WHO pray tell has his position now?

The Copyright Office has not yet canceled the Zarya registration, link to twitter.com

DALL-E, draw me a railway line going under a bridge in the style of Thomas Kinkade, but without the cute lights.

Ha!

I’ve produced wildly different pictures by altering 3-4 different parameters in my Spirograph set.

Question, who owned those pictures? Hasbro or me?

Sounds like somebody didn’t read paragraphs 139 through 143 of their Spirograph EULA!

Joke is on them then; I was a minor 😉

More seriously, I see the OpenAI asserts that *it* is the original copyright holder (who then “assigns to you all its right, title and interest in and to Output.”) Presumably, a scheme to avoid plaintiffs for a while.

I don’t see how that would ever hold up. They have no “there” there, as copyright cannot exist until the person uses the tool – and that’s after the asserted contract point. There is no “copyright” in future work, not yet embodied in a fixed medium.

In fairness, I should add that it’s only an implicit assertion, i.e., they need to have owned something to assign it.

My problem wrt copyright is less the fixation issue, than the lack of creative input i.e., DALL-E is just Spirograph for adults, a tool that helps you produce better art. And, like that old Spirograph set, copyright to the output work belongs to the person who selected the input parameters, not the tool mfg.

+1

IF YOU ASK ANYONE KINKADE IS BEING INFRINGED BY A BOT

Given Naruto, I am not seeing how the thrust into Copyright moves this case in Thaler’s direction.

It doesn’t.

Comments are closed.