“Perhaps the most salient difference between DABUS and mainstream generative programs is that DABUS has no clearcut goals. It learns from its environment and then contemplates, arriving at complex concepts from its accumulated memories.” – Dr. Thaler

Image: LinkedIn

The issue of AI inventorship in the United States remains at large following the Supreme Court’s denial of cert in Thaler v. Vidal, meaning that the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) finding that AI cannot be considered a named inventor to a patent application remains the law of the land. Now that the agency is seeking public comments on the issue of AI inventorship, I reached out to Dr. Thaler to get his comments on the current AI inventorship debate within the patent space. When I asked Dr. Thaler how he felt about the discussions surrounding AI at large, here is what he told me:

Thaler: In my brutally honest opinion, the whole field of AI is dominated by marketing hype. To be known in the field, one must belong to the right industrial or academic circle and pay large amounts to PR departments/firms to stand out. Furthermore, there seems to be a lot of misleading news lately about so-called ‘generative AI.’ Truth be known, AI has always been about generative AI— systems that take inputs and produce outputs.

In contrast, back in the 1980s and 90s I began to question that wisdom, conducting experiments in which I supplied no inputs at all to the system, an artificial neural net, and it produced meaningful outputs. In fact, I could throw utter nonsense at the net and witness meaningful outputs from it, thus violating the long-standing GIGO principle (garbage in, garbage out).

One technology that has been overly hyped is ChatGPT. Under the hood, the system uses 50+ year-old technology, but has benefitted from having a small army of engineers behind it, as well as extensive data that it can train upon. In my honest opinion, it works well when queried about common knowledge, but fails miserably when questioned about STEM subjects. Even worse, it has been selectively trained by those engineers who have a readily identifiable political leaning.

In our conversation below, we explore the unique nature of Thaler’s AI machine, DABUS (“Device for the Autonomous Bootstrapping of Unified Sentience”)and why Dr. Thaler felt that DABUS was the sole inventor of his claimed inventions, rather thanany of the humans who built or trained DABUS. Ultimately, we talk about the meaning of “conception” in the modern computer age. Will our patent laws hold up?

Are the Current Laws of Conception Workable?

Now that cert has been denied to Thaler v. Vidal, the current law of the land does not seem to make room for machine inventions. At this point, there still seems to be widespread consensus that patent protection should be afforded to AI-generated inventions in order to capture the next generation of innovations. But patent policy makers now must decide whether the current inventorship system is sufficient, or whether a sui generis system is needed.

In Dr. Thaler’s case, the USPTO and the courts were confronted with the question of AI inventorship based on a machine that, uniquely, did not operate from any human input:

Xie: You consider DABUS the sole creator of its concepts. I assume that is because you did not provide the AI with a prompt.

Thaler: No, there were no prompts. DABUS contemplated its universe, came to many revelations, driven by its own subjective feelings (i.e., sentience). It is the sole creator. In terms of function, DABUS simply absorbs memories of ‘pieces’ of the external world, thereafter, combining multimedia memories of these fragments together to create new concepts. In a sense, it contemplates its external world while in a state of sensory deprivation, as witness nets absorb memories of what was is being imagined. The dominant memories within such witness nets are the most salient concepts cumulatively synthesized.

The witness on the other hand may be interrogated via keywords, pictures, sounds, etc. to activate related concepts formed. In fact, the system may be presented with graphical representations of the memory chains sought, seeding a larger chain offering all the AI knows about a subject, offering a much more efficient and unambiguous alternative to natural language prompts.

Xie: Why didn’t you feel that you should list as a creator the person who trained the AI?

Thaler: My parents, educators, and an assortment of historical figures trained me by exposing me to concepts and their consequences. However, I was not asked to name all my ancestors back to Adam and Eve when filing patent or copyright applications. That’s because my learning had temporarily ceased as I conceptualized and mentally experimented with the resulting ideas. In the same way, training via concepts and repercussions had momentarily halted in DABUS as the system entered a free-run period during which it synthesized new ideas.

Xie: What sorts of training data does DABUS operate from?

Thaler: There is no training data per se. Let me explain.

Typically, in training an artificial neural net, data records are presented rapidly, one by one, each consisting of an input pattern and the desired output. As the net trains, it finds the relationships between input and output patterns, thus becoming a ‘mapping.’ Basically, that’s how ChatGPT works, learning to map between prompts and likely answers, after repetitive training sessions involving many people.

In contrast, DABUS does not create such mappings using files containing input-output data. If the system detects some new pattern in the environment, it is absorbed as a memory within one of its nets. Later, when the system simultaneously detects two or more features, the respective nets bind together using simple mathematical rules, leading to chains of nets representing both concepts and their repercussions. Then, if the associative chain leads to a hot button net, the entire chain is reinforced through either the lowering or raising of simulated neurotransmitter level. Otherwise, the concept weakens and ‘dissolves’ through random disturbances injected into its linkages.

Similarly, a witness net is observing the shapes formed by these chaining nets, once again forming memories of them. Later, after prolonged periods of stochastic perturbation and learning, this witness may be interrogated for specific memories.

Xie: How does DABUS differ from other mainstream AI programs such as ChatGPT?

Thaler: DABUS is a novel, useful, and hence, patented, AI paradigm, involving both hardware and software, that differs considerably from a multilayer perceptron like ChatGPT. It consists of many artificial neural nets that are transiently interconnecting to form geometrical shapes representing both concepts and their repercussions. In fact, we see something similar when watching functional brain scans as different brain centers simultaneously light up to represent complex concepts and juxtapositional invention. Thereafter, other regions light up in succession, indicating the predicted consequences of said concept. In other words, associative chains of nets form that typically terminate on nets containing memories of salient and/or impactful issues.

In a similar manner, the nets in DABUS similarly chain until they connect with nets containing salient memories. Another neural system called a ‘foveator’ detects the incorporation of such ‘hot buttons’ into these chains, at which point simulated neurotransmitters are secreted to reinforce the entire chain consisting of both the concept and its consequences. Repeated cycles of reinforcement and weakening of chains result in the selective ripening of only notions most important to the system. It is especially important to note that when a chatbot is not in use, it is completely dormant. In contrast, DABUS systems keep contemplating what they have learned and amassing more and more revelations about the world they have been observing, either through sensors or human input.

In all fairness though, DABUS is more of a proof-of-principle experiment conducted by just one person, unlike ChatGPT which is a well-financed collaboration among thousands, resulting in a nearly productized software system.

Perhaps the most salient difference between DABUS and mainstream generative programs is that DABUS has no clearcut goals. It learns from its environment and then contemplates, arriving at complex concepts from its accumulated memories. Later, the system may be interrogated for those ideas that fulfill a specific goal.

One of the most controversial aspects of the AI inventorship question is the idea of machines owning property in the form of patent rights. A common proposed solution is to make the law such that the ownership of AI generated inventions be automatically bestowed to the owner of the AI model. This may seem like an acceptable solution in a situation like DABUS, a machine that can generate output without human prompts – in fact Dr. Thaler executed an assignment provision on behalf of DABUS in his patent applications. But this approach will likely result in “lost inventors.”

One complication is the case of fine-tuning AI models, in which someone takes a more general model already trained by another group or individual in order to fine-tune that model on a smaller dataset to make it perform better at a more specific task. For example, radiologists are fine-tuning large language models to be adapted specifically for radiology report classification. One of the general models that these fine-tuners used is the language model, BERT. Would it be fair for all patent rights protecting the fine-tuned radiology model to be automatically assigned to the owners of BERT (Google) as a matter of course rather than the radiologists who endeavored the fine-tuning? That is a question that the policy makers will have to decide, and I hope that they take into consideration.

What is ‘Conception’ in the World of Generative AI and Who are the Parties that Can Conceive?

In the United States, the law of inventorship is governed by “conception.” One must contribute to the conception to be an inventor.” In re Hardee, 223 USPQ 1122, 1123 (Comm’r Pat. 1984). Conception has been defined as “the complete performance of the mental part of the inventive act” and it is “the formation in the mind of the inventor of a definite and permanent idea of the complete and operative invention as it is thereafter to be applied in practice….” Townsend v. Smith, 36 F.2d 292, 295, 4 USPQ 269, 271 (CCPA 1929). The inventor must form a definite and permanent idea of the complete and operable invention to establish conception. Bosies v. Benedict, 27 F.3d 539, 543 (Fed. Cir. 1994).

Now the question becomes what does “conception” mean in the world of generative AI, especially when the laws do not require reduction to practice? When it comes to generative AI, does the machine really solely conduct all the “conception” as defined by the law? What are the human components of conception to generative AI? I asked Dr. Thaler to explain, as one skilled in the AI art, what is the scope of human-to-machine interaction in the world of generative AI. My goal is to deduce who can be attributed with conception in this vast innovative field – human, machine, or both?

Xie: Please describe the level of human involvement for different types of generative AI systems that you are familiar with.

Thaler:

- Expert Systems – Assemble knowledge bases as well as rules for an inference engine.

- Genetic Algorithms – Deduce/develop constraint relations to avoid combinatorial explosion as phenotypes evolve.

- Artificial Neural Nets – Assemble training data, optimize network architecture and learning parameters.

- Creativity Machines – Assemble training data, optimize network architectures and learning parameters.

- DABUS – Occasionally correct system as would a parent.

Xie: In terms of writing good AI prompts, do you feel that the human prompt writer needs a high degree of technical proficiency? Or can a simply curious mind write good prompts and cause the machine to generate new concepts?

Thaler: As previously stated, there are no prompts as DABUS autonomously contemplates and creates. However, once the system has accumulated discoveries in this manner, it can be interrogated by humans. Note however that even when a human is posing questions to another human, a certain amount of enculturation is required in the subject matter to pose appropriate queries.

So, in answer to your question, some expertise is required if using natural language prompts. However, techniques are now in development here to implement non-linguistic queries, but this methodology is currently proprietary. Nevertheless, a curious mind will suffice, and just a little skill.

Xie: Do you think that proficiency will differ between different technical and/or artistic fields? Say the skill needed to use AI to generate an invention versus a work of art?

Thaler: The prompt skill levels will be about the same using the new approach.

Xie: How long was the creative process with DABUS before you felt that the AI had arrived at a significant concept?

Thaler: That question is difficult to answer because I don’t know when DABUS arrived at any specific concept. It could be within seconds, and it could be weeks, months, or even years, just as in the human case.

Xie: When it comes to different types of AI systems, say a natural language processing program like ChatGPT versus a system like DABUS, do you think the level of human involvement required for reaching a creative concept differs between these types of programs?

Thaler: The level of human involvement in a natural language program like ChatGPT is enormous, with iterative backpropagation training taking place between many different consulting groups. Generation of novel concepts is fast, as intended, but decidedly lacking in diversity. After all, these responses are just slight variations on what humans have told the system previously and therefore do not represent great paradigm shifts.

With DABUS, this Herculean effort is not required. The system simply observes its external world, absorbing both entities and activities. Then, ideas autonomously knit themselves together as humans serving as parents, correcting the child as need be.

Every now and then I hear suggestions among the IP circuit that AI inventorship should be extended to the prompt writer. We may be leaning a bit too far into the Midjourney copyright dilemma with this proposal. When it comes to patents, we must consider the potential for a huge moral hazard if prompt writers are considered inventors. On this issue, I am taking Dr. Thaler’s statements at face value – when it comes to writing a good AI prompt, “a curious mind will suffice and just a little skill.” Allowing for the prompt writer to be considered an AI inventor creates a system that offers high reward for success and absolutely no penalty for bad results or risks. This will incentivize regular people to sit in front of their computers writing AI prompts in the hopes of arriving at a patentable machine, compound or method without needing a great degree of technical skill. A reward of a patent does not seem to be commensurate with the AI prompt writer’s investment in terms of technical skills or costs of investments in many cases, which will not promote the goal of advancing the useful arts.

Seeking Realistic Solutions

In the USPTO’s Request for Comments on AI Inventorship, the agency asked, “How does the use of an AI system in the invention creation process differ from the use of other technical tools?”

I think they are really, really hoping that the public says “IT DOESN’T! Generative AI is just like using Google. Let’s stop worrying about this.”

But that clearly was not the case with DABUS, as Dr. Thaler explained above. In another example, Corey Salsberg from Novartis recently testified at the USPTO’s East Coast Listening Session that Novartis is currently using JT-VAE Generative Modeling (JAEGER), a deep generative approach for small-molecule design that was built on the basis of JT-VAE (the Junction Tree Variational Auto-Encoder), to generate IP with very little contribution from the human inventors.

The output generated by JAEGER can be considered not unlike Google search results. But the issue with this is that, if using JAEGER is akin to using Google, then JAEGER is not an inventor. Yet, it seems as though there is no human inventor in this situation either, as arguably no human meets the requirement of conception in this instance (is a Googler an inventor simply because his search results generated the right answers?). Then we run into the same problem Dr. Thaler encountered at the USPTO in that there is no named inventor, meaning the application is incomplete and will not be examined.

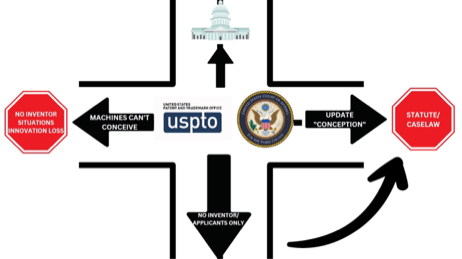

The simplest solution for the USPTO is to alter the current Application Data Sheet (ADS) form to no longer require a list of inventors, but a list of applicants which can include humans or corporate entities. This is a simple approach that does away with all of us having to mull over who contributed to the conception of the invention as defined by the claims, which oftentimes is not straightforward. The downside is that the USPTO is effectively changing the law to a no-inventor system, meaning the change will obviously run into statute and case law and ultimately be struck down as violating 35 USC 100(f). So, that’s out.

This is ultimately the agency’s problem with AI inventorship right now – they are bound by statute and case law governing inventorship and conception. The agency’s AI inventorship Listening Sessions so far seem to suggest that they are considering updating the laws of conception to account for AI. But it just does not seem possible given all the statute and case law.

The USPTO can realistically make a rule simply stating that machines cannot conceive under the current laws. But a system that bars machines from conception can result in situations in which machine-generated inventions will be unpatentable for also lacking a human inventor, like in DABUS’s case and, potentially, Novartis’ JAEGER. This could result in tremendous innovation loss, which undermines the ultimate goal of the USPTO of promoting innovation. The USPTO’s options do not appear to be very plentiful in the matter of AI inventorship:

Our society’s current problems with AI extend far beyond this debate of AI inventorship in the patent space. Our lawmakers should grapple with the greater question regarding the role that AI should be permitted to play in our modern world and in our daily lives. Personally, I believe that the matter of AI inventorship should also be taken up with them. If only they will step up.

![[IPWatchdog Logo]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/themes/IPWatchdog%20-%202023/assets/images/temp/logo-small@2x.png)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/Artificial-Intelligence-2024-REPLAY-sidebar-700x500-corrected.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/UnitedLex-May-2-2024-sidebar-700x500-1.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/Patent-Litigation-Masters-2024-sidebar-700x500-1.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/WEBINAR-336-x-280-px.png)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/2021-Patent-Practice-on-Demand-recorded-Feb-2021-336-x-280.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/Ad-4-The-Invent-Patent-System™.png)

Join the Discussion

7 comments so far.

Pierce Mooney

May 16, 2023 08:48 pmit appears Mergenthaler v. Scudder, 11 App. D.C. 264 (1897) is where “in the mind of the inventor” came from. I think it goes without saying that the application will always be owned by a legal entity (human controlled/owned). The issue is letting a human lie and say they invented something when really they didn’t even do manual prompting to arrive at the patentable solution. A fix is to accept that “in the mind of the a.i. model” is just fine. An A.I.-owning entity can “obtain” the patent according to 101 just fine (see ~35% in on the recording: https://uspto.cosocloud.com/p4luwhjdc51c/)

One Inquiring Mind

May 16, 2023 06:28 amDoes the AI want the patent or does Dr. Thaler want the patent? Did the AI file an application? Did the AI pay the filing, search, and examination fees? Did the AI correspond with the inventor, or did the AI hire legal representation?

Just curious how this is expected to work.

Pro Say

May 15, 2023 02:22 pmThought-provoking this is.

Yet; at least currently (regardless of “terms-twisting” and verbal-gymnastics); there is no there, there.

No human input = No AI inventions.

Furthermore, only Congress has the authority to put anything . . . there.

The PTO’s hands are — thankfully — tied. Tightly.

Max Drei

May 15, 2023 05:20 amThe enquiry should be into the act of “conception”. Suppose that JAEGER can legitimately be said to have “conceived” a “design” corresponding to a “small molecule”. Is that enough to satisfy the statutory requirement to conceive an “invention” eligible for patenting?

Is not a further step needed, namely to assimilate the output of JAEGER and extract from that assimilation a statement in words that is an attempted definition of a patentable inventive concept? Is not the conception of that statement the moment when the inventive concept is captured in words, the first moment when it can be conveyed to another human, to another mind, that is to say, “conceived”?

Pierce Mooney

May 15, 2023 12:15 amGreat points Wen! As a former language processing examiner, the BERT model example especially made me think. It would be good to see some international proposals for solutions. I also agree with your conclusion that law makers need to step up here.

Related, at the USPTO last month, one of the AI Inventorship event speakers’ most interesting conclusions was someone who pointed out that the Townsend v. Smith “in the mind of the inventor” aspect was largely DICTA ! If that is true, I agree that his conclusion seemed to be a promising solution to the issue: we should move away from using that phrase, and towards including “in the mind of the a.i./ml system”.

Pierce Mooney

May 15, 2023 12:13 amGreat points Wen! As a former language processing examiner, the BERT model example especially made me think. I also agree with your conclusion that law makers need to step up here. It would be good to see some international proposals as well.

Related, at the USPTO last month, one of the AI Inventorship event speakers’ most interesting conclusions was someone who pointed out that the Townsend v. Smith “in the mind of the inventor” aspect was largely DICTA ! If that is true, I agree that his conclusion seemed to be a promising solution to the issue: we should move away from using that phrase, and towards including “in the mind of the a.i./ml system”.

Curious

May 14, 2023 10:40 pmSuggestion — if you really want to help us get insight into DABUS and how it works, rather than taking Dr. Thaler’s statements “at face value,” get an AI expert and have him/her help you formulate questions (and follow up questions) to ask of Dr. Thaler.

For example, Thaler says that “[t]here is no training data per se” and “DABUS does not create such mappings using files containing input-output data.” However, Thaler immediately follows those assertions up by stating “If the system detects some new pattern in the environment, it is absorbed as a memory within one of its nets. Later, when the system simultaneously detects two or more features, the respective nets bind together using simple mathematical rules, leading to chains of nets representing both concepts and their repercussions.”

From my experience with AI, the “new pattern in the environment” is an input, and “their repercussions” is an output. As such, Thaler appears to be merely using different terminology for describing the same thing. As another example, Thaler writes that “[i]n terms of function, DABUS simply absorbs memories of ‘pieces’ of the external world, thereafter, combining multimedia memories of these fragments together to create new concepts.” What Thaler calls pieces of the external world are just inputs.

Thaler also writes “In contrast, DABUS systems keep contemplating what they have learned and amassing more and more revelations about the world they have been observing, either through sensors or human input.” The “through sensors or human-input” is, again, examples of inputs.

Thaler also writes “Perhaps the most salient difference between DABUS and mainstream generative programs is that DABUS has no clearcut goals. It learns from its environment and then contemplates, arriving at complex concepts from its accumulated memories. Later, the system may be interrogated for those ideas that fulfill a specific goal.”

The learning from its environment is learning from inputs. Also, what I would like to know is how the DABUS system is interrogated. If the system requires very specific interrogation, this would likely be indicative that the one crafting the interrogation is the inventor. On the other hand, as the interrogation becomes less specific, the less likely the one crafting the interrogation is the inventor.

As indicated by the Examiner above, Thaler’s answers are difficult to parse as they do not use the terminology commonly used by those in the field. This is where an AI expert would prove helpful as such a person would be able to translate what Thaler says into something more useful.