“If Warhol does not get credit for transformative copying, who will? [The decision] will stifle creativity of every sort. It will impede new art and music and literature. It will thwart the expression of new ideas and the attainment of new knowledge. It will make our world poorer.” – Justice Kagan, dissenting

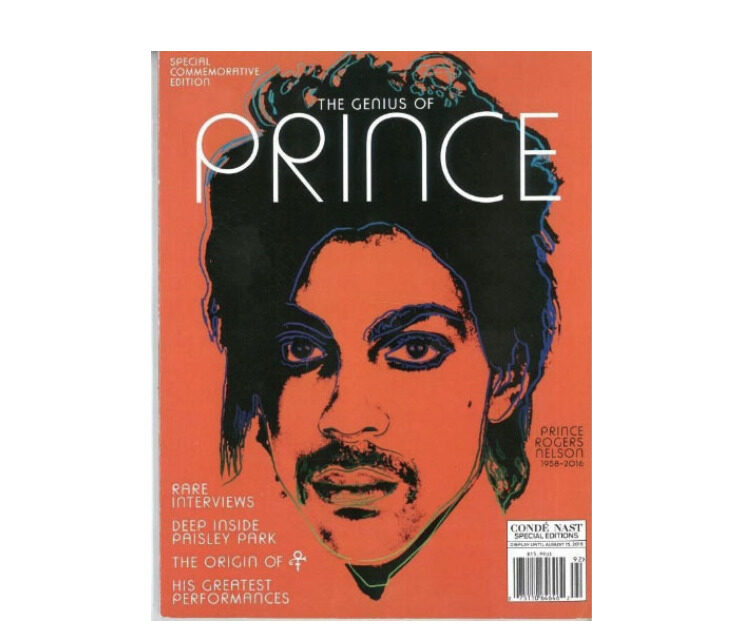

The Supreme Court ruled today in Andy Warhol Foundation v. Goldsmith, Lynn, et. al. that the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit was correct in holding that the Andy Warhol Foundation’s (AWF’s) licensing of an orange silkscreen portrait of the musician Prince, created by Andy Warhol using photographer Lynn Goldsmith’s photo, was not fair. Justices Gorsuch and Jackson authored a concurrence, while Justice Kagan, joined by Chief Justice Roberts, filed a 35-page dissent from Justice Sotomayor’s opinion, in part calling out the majority’s contradictory interpretation of similar facts in the recent Google v. Oracle case.

The Supreme Court ruled today in Andy Warhol Foundation v. Goldsmith, Lynn, et. al. that the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit was correct in holding that the Andy Warhol Foundation’s (AWF’s) licensing of an orange silkscreen portrait of the musician Prince, created by Andy Warhol using photographer Lynn Goldsmith’s photo, was not fair. Justices Gorsuch and Jackson authored a concurrence, while Justice Kagan, joined by Chief Justice Roberts, filed a 35-page dissent from Justice Sotomayor’s opinion, in part calling out the majority’s contradictory interpretation of similar facts in the recent Google v. Oracle case.

The Court granted cert in March 2022, and heard oral arguments in October 2022. The Second Circuit held in March 2021 that “the district court erred in its assessment and application of the fair-use factors and the works in question do not qualify as fair use.”

The majority in today’s ruling agreed, holding that the commercial nature of AWF’s use of the photo “does not favor AWF’s fair use defense to copyright infringement.” However, the majority made it clear that its ruling pertains strictly to the “narrow issue” of whether the first fair use factor weighs in AWF’s favor, “limited to the challenged use.”

AWF had argued that “the Second Circuit’s decision…creates a circuit split and casts a cloud of legal uncertainty over an entire genre of visual art.” And during oral argument, AWF’s counsel, Roman Martinez of Latham & Watkins, said that the transformative meaning of Warhol’s work—the dehumanization of celebrities in pop culture—“puts points on the board” for AWF on factor one of the fair use test, which looks at the purpose and character of the allegedly infringing use.

But Goldsmith countered that AWF’s petition “mischaracterizes” Supreme Court precedent and the Second Circuit’s opinion “in an attempt to manufacture a circuit split that does not exist.” Goldsmith said that the Second Circuit faithfully applied the test for transformativeness and simply found that Warhol’s work failed to “add[] something new, with a further purpose or different character, altering the first with new expression, meaning, or message,” thereby failing the test.

Holding and Dissent

In a nutshell, the majority said that AWF’s licensing in 2016 of Warhol’s “Orange Prince” photo, derived from Goldsmith’s photo, shared “substantially the same purpose” as Goldsmith’s original—i.e. to be used in magazines to illustrate stories about Prince—and AWF’s use of the photo was commercial in nature. These two elements outweigh any transformative nature of AWF’s work, the Court said. And because there was no dispute between the parties that the remaining three fair use factors weighed in Goldsmith’s favor, the majority affirmed.

The Court relied heavily on its precedent in In Campbell v. Acuff-Rose Music, Inc., which said 2 Live Crew’s parody of Roy Orbison’s song “Oh, Pretty Woman” was a fair use, despite the commercial nature of the new 2 Live Crew song. While Campbell described a transformative use as one that “alter[s] the first [work] with new expression, meaning, or message,” that “cannot be read to mean that [the first fair use factor] weighs in favor of any use that adds some new expression, meaning, or message,” wrote the Court. “Otherwise, ‘transformative use’ would swallow the copyright owner’s exclusive right to prepare derivative works.”

Addressing the seeming contradiction between its holding here and the finding in Google v. Oracle that Google’s use of Oracle’s Java application programming interface (“API packages”) did constitute a fair use, the Court explained the distinction in its footnote 8:

Although Google’s use was commercial in nature, it copied Sun’s code, which was “created for use in desktop and laptop computers,” “only insofar as needed to include tasks that would be useful in smartphone[s].” Id., at ___ (slip op., at 26). That is, Google put Sun’s code to use in the “distinct and different computing environment” of its own Android platform, a new system created for new products. Ibid. Moreover, the use was justified in that context because “shared interfaces are necessary for different programs to speak to each other” and because “reimplementation of interfaces is necessary if programmers are to be able to use their acquired skills.”

But Kagan, dissenting, blasted the majority for its approach, explaining that Warhol’s works represent exactly the kind of transformative art that favors a fair use finding, as articulated in Google, where the court referred to an artistic painting that replicates a copyrighted advertising logo to make a comment about consumerism—as Warhol did with his famed Campbell’s Soup painting—as an example of a transformative fair use. “That Court would have told this one to go back to school,” the dissent wrote.

Responding to this criticism, the majority said that “not all of Warhol’s works, nor all uses of them, give rise to the same fair use analysis.” The opinion explained:

The purpose of Campbell’s logo is to advertise soup. Warhol’s canvases do not share that purpose. Rather, the Soup Cans series uses Campbell’s copyrighted work for an artistic commentary on consumerism, a purpose that is orthogonal to advertising soup. The use therefore does not supersede the objects of the advertising logo.

In footnote 15, the Court added that “[t]he situation might be different if AWF licensed Warhol’s Soup Cans to a soup business to serve as its logo.”

Kagan also slammed the majority for its hyper-focus on the dissent, accusing it of disingenuously characterizing the dissent as having “no theory” and “[n]o reason” despite then spending “pages of commentary and fistfuls of come-back footnotes” on it. She painted a dire picture for the future of visual art as a result of the ruling, asking, “If Warhol does not get credit for transformative copying, who will?” The decision, she said, “will stifle creativity of every sort. It will impede new art and music and literature. It will thwart the expression of new ideas and the attainment of new knowledge. It will make our world poorer.”

Joel Wachs, President of The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, sent the following statement to IPWatchdog in response to the ruling:

“We respectfully disagree with the Court’s ruling that the 2016 licensing of Orange Prince was not protected by the fair use doctrine. At the same time, we welcome the Court’s clarification that its decision is limited to that single licensing and does not question the legality of Andy Warhol’s creation of the Prince Series in 1984. Going forward, we will continue standing up for the rights of artists to create transformative works under the Copyright Act and the First Amendment.”

Early Perspectives

Preetha Chakrabarti of Crowell & Moring said the decision “is certainly concerning for artists who monetize their work,” particularly in the context of an increasingly digital world. Chakrabarti asked:

of Crowell & Moring said the decision “is certainly concerning for artists who monetize their work,” particularly in the context of an increasingly digital world. Chakrabarti asked:

“Will the commercial nature of an arguably transformative work now create a rebuttable presumption of infringement? What does this mean for all the digital recreations of brick-and-mortar art that now pervade our screens—and lives? Will it be another Warhol— “the avatar of transformative copying,” as the Court in dissent calls him here—piece that creates a legal ruckus and gives us more clarification? Or will it be the next artist whose work is distributed by NFT to do so? As often the case, we’ll have to see—be it through our VR headset of otherwise.”

Here are some other initial takes on the decision:

Bruce Ewing

Dorsey & Whitney

“The decision is narrow in that it addresses only: (i) the licensing to Conde Nast of Andy Warhol’s “Orange Prince” based on Lynn Goldsmith’s copyrighted photo; and (ii) whether the first statutory fair use factor – the purpose and character of the use – favors the Andy Warhol Foundation.

Under today’s ruling, while the question of whether a later work has transformed a prior work by adding new meaning or message remains relevant, such additions will not by themselves tilt the first factor in favor of fair use, as most cases had held previously. Indeed, under today’s ruling, the first factor will only favor fair use if the newly added material rises to such a sufficiently transformative level that the new work achieves a different purpose than the prior work, and therefore does not supersede it.

The Court’s majority took great pains to note that it was only deciding this narrow issue concerned with one fair use factor, assessed in the context of one specific use. Indeed, the concurrence from Justices Jackson and Gorsuch noted that all other issues, including whether the “Orange Prince” as licensed by the Warhol Foundation to Conde Nast actually infringed the Goldsmith photo, remained to be addressed during further proceedings.”

Bill Frankel

Crowell & Moring

“In its application of the first fair use factor (purpose and character of the use) and its holding that AWF’s use of the Goldsmith Prince photo did not constitute a fair use, the Supreme Court essentially concluded that Andy Warhol used too much of the Goldsmith work primarily for a similar commercial purpose and this was too much to abide. Specifically, the Court observed that simply adding new meaning or expression to a work is an insufficient reason to permit copying for free; rather, it is necessary to assess the degree to which a challenged use has a further purpose or a different character than that of the original. Here, the Court determined that AWF used the photograph in a commercial manner, and for the same purpose as Goldsmith, when it licensed the Orange Prince to Conde Nast. Against this reasoning and result, Justice Kagan, joined by Chief Justice Roberts, argues in dissent that the majority misunderstands Andy Warhol’s art and belittles the significance of its transformative nature, leaving the first fair use factor in shambles.

This ruling is likely to have significant ramifications in the art world. It places limitations on artistic freedom for appropriation artists by narrowing the interpretation of fair use as applied to their works of art. It has the potential to affect the market and value for AWF’s Prince Series works and other appropriation artwork, and poses copyright risks and uncertainties for art dealers, collectors, and museums. Moreover, the ruling has potential ramifications beyond the art world. The Court’s reframing of what constitutes transformative is likely to have an impact with respect to other licensed works – generative AI in particular. Currently pending, and foundational, legal cases dealing with text, code, and artwork generated by AI systems all involve significant fair use issues.”

Mitch Glazier

Mitch Glazier

RIAA

“We applaud the Supreme Court’s considered and thoughtful decision that claims of ‘transformative use’ cannot undermine the basic rights given to all creators under the Copyright Act. Lower courts have misconstrued fair use for too long and we are grateful the Supreme Court has reaffirmed the core purposes of copyright. We hope those who have relied on distorted – and now discredited – claims of ‘transformative use,’ such as those who use copyrighted works to train artificial intelligence systems without authorization, will revisit their practices in light of this important ruling.”

Randy McCarthy

Randy McCarthy

Hall Estill

“This is an interesting development in that it provides further guidance on how the courts will examine questions relating to transformation.”

One point that appears to be important to both the Supreme Court and the Second Circuit is that the commercial purposes of both were the same. A second related point important to both Courts was the fact that the original work was clearly identifiable when viewing the copy. Both of these factors may be significantly different when using copyrighted works in an AI system, whether as training data, input data or part of the internal algorithm.

In other words, it is evident that ‘transformation’ for purposes of copyright law in an AI system context will continue to rely heavily upon what the resulting work looks like in comparison to the original work. This is how existing copyright law works as well. This should be a win for AI system users, provided that the output is sufficiently transformed and the input cannot be easily identified from an examination of the output content.”

Nicholas O’Donnell

Art, Cultural Property and Heritage Law Committee of the International Bar Association

Sullivan & Worcester

“This is a case about two images proposed to be used in an article about Prince in a commercial context. The Court carefully avoids many of the broader questions about the limits of fair use in visual art, which is an interesting choice. Finally, and most significantly, the court categorically rejected the idea that any new meaning or message qualifies as a fair use in and of itself, holding that such an exception would swallow the fair use rule. Given the specific facts of the case, I suspect that last part will be the most important part of the ruling.”

![[IPWatchdog Logo]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/themes/IPWatchdog%20-%202023/assets/images/temp/logo-small@2x.png)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/Patent-Litigation-Masters-2024-sidebar-early-bird-ends-Apr-21-last-chance-700x500-1.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/WEBINAR-336-x-280-px.png)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/2021-Patent-Practice-on-Demand-recorded-Feb-2021-336-x-280.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/Ad-4-The-Invent-Patent-System™.png)

Join the Discussion

No comments yet.