by Dennis Crouch

On October 12, 2022, the Supreme Court will hear oral arguments in the fair use copyright case of Andy Warhol Foundation, Inc. v. Goldsmith, Docket No. 21-869 (2022). Roman Martinez (Latham Watkins) is set to argue for Warhol and Lisa Blatt (Williams Connolly) for Goldsmith. The Court is also giving 15 minutes to Yaria Dubin (USDOJ) who also filed a brief supporting Goldsmith.

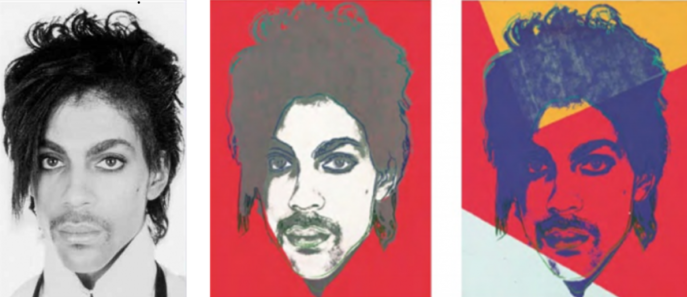

Andy Warhol admittedly used Lynn Goldmith’s copyrighted photographs of Prince as the basis for his set of sixteen silkscreens. Warhol’s Estate argues that the artworks represent a commentary on the dehumanizing nature of celebrity whereas the Goldsmith photos merely reflect Prince in his unique human form.

The Supreme Court has taken-up the case to consider the extent that the doctrine of transformative fair use should value “differences in meaning or message,” especially in cases where the works share core artistic elements and have the same purpose.

Question presented: Whether a work of art is “transformative” when it conveys a different meaning or message from its source material (as the Supreme Court, U.S. Court of Appeals for the 9th Circuit, and other courts of appeals have held), or whether a court is forbidden from considering the meaning of the accused work where it “recognizably deriv[es] from” its source material (as the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 2nd Circuit has held).

Although Andy Warhol is dead, his art, legacy, copyrights, and potential copy-wrongs live on. In the 1980s, Warhol created a set of silkscreens of the musician Prince. Prince did not personally model for Warhol. Rather, Warhol worked from a set of studio photographs by famed celebrity photographer Lynn Goldsmith. Vanity Fair had commissioned Warhol to make an illustration for its 1984 article on Prince. As part of that process, the magazine obtained a license from Goldsmith, but only for the limited use as an “artists reference” for an image to be published in Vanity Fair magazine. The published article acknowledges Goldsmith. One reason why the magazine knew to reach-out to Goldsmith was that her photos had also previously been used as magazine cover-art. Warhol took some liberties that went beyond the original license and created a set of sixteen Prince silkscreens. Those originals have been sold and reproduced in various forms and in ways that go well beyond the original license obtained by Vanity Fair. (Warhol was never personally a party to the license).

Warhol claimed copyright over his artistic creations and his Estate continues to receive royalty revenue long after his death in 1987. Goldsmith argues that her copyrighted photographs serve as the underlying basis for Warhol’s art and that she is owed additional royalties. After unsuccessful negotiations, Warhol’s Estate sued for a declaratory judgment and initially won. In particular, the SDNY District Court granted summary judgment of no-infringement based upon the doctrine of transformative fair use. The district court particularly compared the works “side-by-side” and concluded that Warhol’s creation had a “different character, a new expression, and employs new aesthetics with [distinct] creative and communicative results.” This test quoted comes from another famous a photo-transformation case, Patrick Cariou v. Richard Prince, 714 F. 3d 694 (2d Cir. 2013).

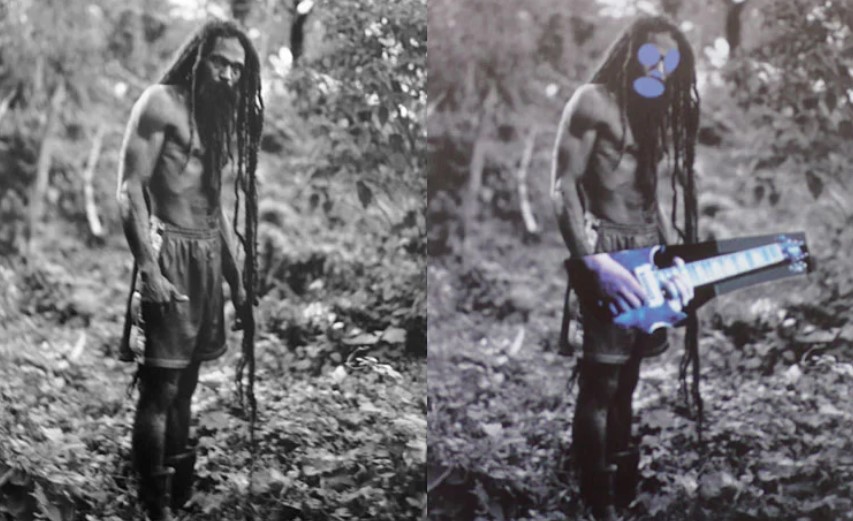

Richard Prince had modified Cariou’s photographs of a Jamaican Rastafarian community and exhibited his work as “appropriation art.” The copier eventually won, with an appellate holding that the majority of Richard Prince’s works were clearly transformative in their newly presented “aesthetic.” In that case, the 2nd Circuit also held that the new work can still be a transformative fair use even if not a “satire or parody” of the original work, or even be commenting on the original work in any way. That said, uses of someone’s copyright work for a the purpose of parody, news reporting, comment, or criticism make it much more likely that the use will be deemed a fair use.

After losing at the district court, Goldsmith appealed to the Second Circuit who reversed and instead concluded that Warhol’s art was “substantially similar to the Goldsmith Photograph as a matter of law” and “all four [fair use] factors favor Goldsmith.” The appellate court warned against too broadly reading its prior Cariou decision.

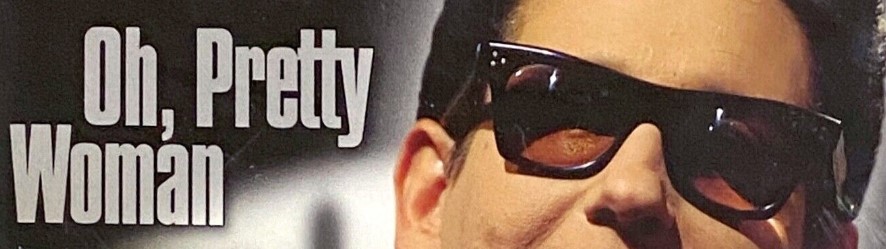

Warhol’s key legal precedent on point is Campbell v. Acuff-Rose Music, Inc., 510 U.S. 569 (1994). Campbell involved 2 Live Crew’s parody of the famous Roy Orbison song “Oh, Pretty Woman.” The unanimous decision by Justice Kennedy delves into the first statutory fair use factor (“purpose and character of the use”) and distinguishes between (a) uses that simply replace or supersedes the original work and (b) those that are transformative of the original work. The more transformative a work, the more likely that it will be deemed a fair use and thus not infringing. Campbell goes further and explains that transformativeness is not solely about new expression—it is also focused on whether the new work has “a further purpose or different character, altering the first with new expression, meaning, or message.”

Goldsmith argues that transformative meaning is only one element of a wide-ranging fair use analysis appropriately conducted by the Second Circuit. As the Supreme Court recently explained in Google v. Oracle decision, the process is a “a holistic, context-sensitive inquiry” operating without any “bright line rules.”

The Copyright Act promises the original creator some amount of control over similar and follow-on works. In fact, the copyright owner is given exclusive rights to control preparation of any “derivative works based upon the copyrighted work.” For Warhol to rely entirely upon transformativness for his fair-use defense, the use must be so transformative as to leap beyond these derivative use rights. Still, Warhol argues that the Second Circuit erred by refusing to give weight to the transformed “meaning or message” even if underlying elements of his artwork were similar to elements of the original photographs. As the Court wrote in Campbell, transformative uses “lie at the heart of the fair use doctrine’s guarantee of breathing space within the confines of copyright.” Warhol’s particular complaint with the Second Circuit is its apparent ruling that “a new work that indisputably conveys a distinct meaning or message” will still not be deemed transformative if its expression unduly retains “the essential elements of its source material.” Warhol argues that legal conclusion was recently rejected by the Supreme Court in Google. Goldsmith responds that Warhol is misreading the Second Circuit’s decision – making a caricature of its holding. Rather, Goldsmith argues, the Second Circuit properly weighed all the fair use factors. Further, although “message and meaning” is an aspect of fair use, it not found in the statutory nor intended by its creator (Judge Leval) to fully explain fair use.

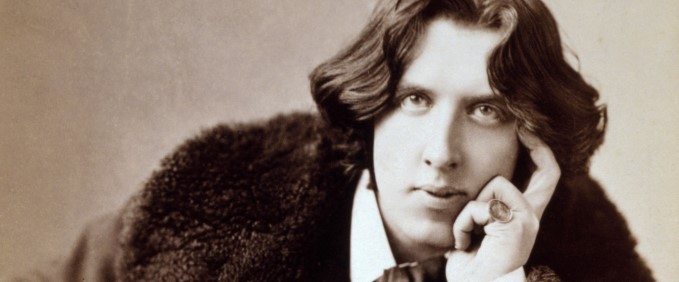

Goldsmith also cites a list of historic cases where “conveying new meanings or messages did not save infringers.” One famous case is the Supreme Court’s 1884 decision in Burrow-Giles Lithographic Co. v. Sarony involving a photograph and lithograph copy of the famous playwright Oscar Wilde. Sarony was the first Supreme Court case confirming copyright protection in photographs. Goldsmith notes that the lithographer made a number of stylistic changes to Wilde’s appearance—shifting Wilde’s gaze from a “thousand-yard stare [of a] calculated ennui” to a “soulful gaze and brooding eyebrows [of a] dashing poet.” Despite these shifts, everyone seemed to agree that infringement was clear: “the lithograph was so obviously nontransformative the lithographer did not even try to raise fair use.” Goldsmith’s description of the images of Wilde has the reverb of a pedantic academic art critic—and one may suspect that tone was strategic in order to demonstrate the potentially ridiculous nature of the inquiry into the “message and meaning” of artistic works.

A large number of amicus briefs were filed in the case. The most important of these is likely the brief of the Solicitor General filed on behalf of the U.S. Government (Biden Administration). The government brief focuses on transformative-use and notes that the Goldsmith and Warhol works have been used for the same purpose (republication in magazine articles about Prince) and do not involve a parody. In this same-use scenario, fair use is much less likely because the new work can be seen as little more than a replacement of the original. Regarding the meaning or message intended by Warhol, the government argues that Warhol failed to explain why he needed to reproduce Goldsmith’s work in order for that expression to take place. Thus, the government is attempting to cabin-in the transformative meaning doctrines to areas where the copying is further justified by reasoning or evidence.

The case’s impact on appropriation art and documentary filmmaking is easy to see, but there are other areas that may also see some big shifts depending upon the Supreme Court’s outcome. Although Warhol used pre-computer technology for his screen printing, the case has important implications for online copyright protections in a world of digital cut-and-paste and fingertip access to AI tools to transform digital works. You may have even seen apps that automatically transform photos into a Warhol-style work. A simple and broad holding from the Supreme Court supporting fair use would give substantial space allow these creative activities (and app development) to expand. But, that would be to the detriment of original creators seeking to protect their copyrights. A win for Goldsmith may require a re-tooling of these apps in order to fit within the stricter fair use requirements.

In his amicus brief, Berkeley Professor Peter Menell argues for Goldsmith, writing that “the Prince series consists of unauthorized derivative works prepared for a commercial purpose and without substantial transformative qualities.” Although Warhol’s work has become iconic within our culture, classifying the work as a “derivative work” creates the quirky conundrum that Warhol’s estate holds no copyright at all. This ruling then might extend to other areas—such as museum exhibits (since Goldsmith would then own the right to public display). I will note that Warhol already paid licensing fees to the owner of the underlying work in a number of situations, including for his use of Henri Dauman’s photo of Jacqueline Kennedy that had appeared in LIFE magazine.

This is not exactly a free speech case, but “meaning and message” certainly seem like forms of protected speech. In earlier cases, the Supreme Court ruled that fair use is a stand-in for First Amendment protections in the copyright world. We have seen copyright used in ways akin to SLAPP actions as well as by artists who do not want their work used to support unworthy causes (such as by politicians they oppose). The outcome here will shift those activities, either in favor of control by the original copyright holder, or more liberty to the potential (unwanted) user.

FYI — IPWatchdog has a thread with a link to the oral arguments.

“famed celebrity photographer Lynn Goldsmith”

Not that “famed” outside of her field. This case will provide her with more name recognition than her photographic work ever did.

Are you trying to make her case for her (and do you realize that “she did not get her just recognition while Wharhol did” supports her case)?

I wonder if there is a Liberal Left Intersectionality Equity “Improper Appropriation” angle that would selectively limit any Fair Use arguments…

That’s an informative & balanced post, thanks Prof Crouch.

I am a bit surprised that the (admittedly tenuous) patent angle — the “transformative” software ‘linking words’ — was not tied into this case.

There, “transformative” was “transformed” to be an ‘out’ of nearly unbelievable proportions.

Here, with the focus fully on Copyright, and with BOTH sides aiming for the High Ground of ‘protecting expression,’ both the battle and the result should be Entertaining.

… to clarify, by “tied into,” I did mean that the patent implications be explored.

Comments are closed.