by Dennis Crouch

The law of appellate jurisdiction routes almost every patent appeal to the Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit. This result is by design to ensure more national uniformity in application of the U.S. patent laws. The court’s recent decision in Teradata Corp. v. SAP SE, 22-1286 (Fed. Cir. Aug. 1, 2023) provides an exception to the general rule. In its decision, the Federal Circuit held it lacked jurisdiction over Teradata’s appeal because the patent infringement allegations only been raised in a permissive counterclaim. Although the counterclaims might have been compulsory if compared against Teradata’s original complaint, during the litigation Teradata narrowed its claims in a way that caused separation from the counterclaims.

After a brief partnership pursued under an NDA, SAP began offering a product similar to that of Teradata. Teradata then sued for trade secret misappropriation and antitrust violations. SAP responded with denials and also added patent infringement counterclaims.

Counterclaims: The Federal Rules of Civil Procedure permit a defendant to file counterclaims against the plaintiff. The rules divide the counterclaims roughly into two categories: compulsory and permissive. Although no one actually forces defendant to any counterclaims, failure to assert the compulsory counterclaims is seen as a forfeiture of those claims. Permissive counterclaims are not lost and instead can be raised in a separate, subsequent lawsuit (so long as a statute of limitations has not run, etc.). The rules spell out the following test for compulsory counterclaims:

(A) arises out of the transaction or occurrence that is the subject matter of the opposing party’s claim; and (B) does not require adding another party over whom the court cannot acquire jurisdiction.

FRCP 13(a). Compulsory Counterclaims are important for Federal Circuit jurisdiction because the court’s jurisdictional statute routes cases to the Federal Circuit if either (1) the plaintiff asserts a clam that arises under the US patent laws; or (2) a party asserts a compulsory counterclaim that arises under the US patent laws. Note here the gap — The Federal Circuit does not get jurisdiction if only patent claim is filed as a permissive counterclaim (or a crossclaim or third-party claim). A final quirk of the appellate jurisdiction is that the jurisdiction statute applies even if non-patent issues are the only ones being appealed.

In Teradata, the district court initially declined to sever SAP’s patent, finding they arose from the same transaction or occurrence as Teradata’s claims. Eventually though the district court entered summary judgment on the antitrust and certain “technical” trade secret claims in SAP’s favor. The court then entered partial final judgment under Rule 54(b) on those claims while staying remaining “business” trade secrets claim and the patent counterclaims. R.54(b) partial final judgment is designed to sever aspects of the case and allow those to be immediately appealed.

Teradata appealed the antitrust and trade secret losses to the Federal Circuit. The court has rejected the appeal, holding that it lacks jurisdiction over Teradata’s appeal because SAP’s patent infringement counterclaims were not compulsory. Rather, holding the appeal should be heard by the appropriate regional circuit court of appeals. For this case that is the 9th Circuit because the lower court is located in Northern California.

The Federal Circuit applies three tests in analyzing the same transaction test quoted above from R.13: (1) whether the legal and factual issues are largely the same; (2) whether substantially the same evidence supports or refutes the claims; and (3) whether there is a logical relationship between the claims. In this analysis, the court looks to the complaints and counterclaims as filed. In addition, the Federal Circuit treats claims dismissed without prejudice as having never been filed. Chamberlain Group, Inc. v. Skylink Technologies, Inc., 381 F.3d 1178, 1189 (Fed. Cir. 2004)

= = =

At the district court, Teradata was seeking to have the patent claims severed for a separate trial and, at that time, SAP provided evidence it claimed “demonstrates the substantial overlap between Teradata’s alleged trade secrets and SAP’s asserted patents.” This statement on the record apparently occurred after the narrowing of the trade secrets claims. On appeal the sides were reversed. In particular, SAP stepped back from the argument because it preferred to have the 9th Circuit decide the case rather than the Federal Circuit. When questioned about its prior statements, SAP responded that estoppel cannot be used to shift a court’s jurisdictional requirements.

= = =

A strange aspect of the case has to do with the trade secret claims that were dropped during litigation. There does not appear to be an express statement in the record that they were dropped “without prejudice.” And, even if they were dropped without prejudice, res judicata likely still applies to block those trade secrecy claims from being raised in a subsequent lawsuit. Res judicata would apply because they are clearly part of the same transaction-or-occurrence of the other trade secrecy claims that were litigated. During oral arguments, Judge Taranto asked an astute question of SAP’s lawyers seeking an admission that Teradata would have a right to relitigate those claims. SAP’s lawyers refused to make that admission. The opinion itself offers nothing here and appears to simply assume that the dismissals were without prejudice.

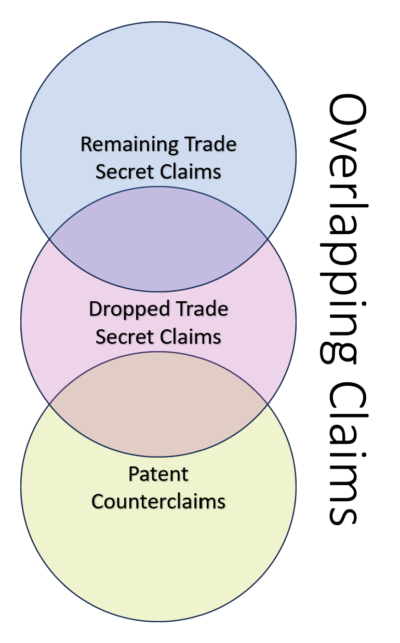

Not a perfect triangle: Even though the dropped trade secret claims likely relate to the same transaction or occurrence as the remaining “batched merge” trade secret claims; AND the dropped trade secret claims likely relate to the same transaction or occurrence as SAP’s patent counterclaims; It does NOT necessarily follow that the remaining “batched merge” trade secret claims arise from the same transaction or occurrence as the patent counterclaims. The relationship between the claims is not transitive – each comparison must be made directly based on the elements and facts required to prove each claim.

= = =

The underlying appeal is interesting and relates to per se antitrust violations and market analysis.

Awesome to see those indictments yesterday. In a sane world that truly cared about democracy, each of those disgusting people would already have been hung and buried but if I live to see them die in jail that will suffice.

Not quite sure what this means, but there is a new opinion out this morning with Judge Newman on the panel.

And—God bless her—Judge Newman’s dissent is in fine form. This is the opening paragraph:

Read the rest. It is masterful.

Uh, it’s barely 4 pages. And most of that is just blockquotes.

Brevity—as they say—is the soul of wit, and “[a]n apt quotation is like a lamp which flings its light over the whole sentence.”

Well said.

She had a dissent in a June 6th case, too. So, I wouldn’t read too much into this.

I would have written less if I had more time.

This is from the majority opinion:

As we later explained, “[t]he patent did not merely claim this enhancement to the computer memory system; it explained how it worked, appending ‘263 frames of computer code.’” Univ. of Fla. Research Found., Inc. v. GE Co., 916 F.3d 1363, 1368 (Fed. Cir. 2019) (distinguishing the claims in Visual Memory). The patents here, by contrast, fail to explain the “how.”

The claims are supposed to enable the invention. Look at 35 USC 112(b) Their purpose is to distinguish the claimed invention over the prior art (i.e., “particularly pointing out and distinctly claiming the subject matter”). It is the role of the specification to explain the “how.” See 35 USC 112(A), (“[t]he specification shall contain a written description of the invention, and of the manner and process of making and using it … to enable any person skilled in the art … to make and use the same”).

In layman’s terms. The claims say “this is why we are different.” The specification says “this is how the invention works.”

The Federal Circuit is essentially rewriting the statutes so as to require (under 101) that the claims do the work of the specification. While 112 case law regarding enablement (i.e., the “how”) takes into account the knowledge of one skilled in the art, this apparently does not hold true under their 101 analysis.

The upshot of all of this is that the Federal Circuit is telling inventors (and practitioners) to put more stuff into the claims (i.e., tell them “how” it works). The problem is that when this extra stuff is put into the claims the Federal Circuit dismisses it as not being inventive — patent owners cannot win either way.

Regardless, the case law is hopelessly inconsistent. Just compare these claims to the claims of DDR Holdings, which were criticized (in the dissent) for not explaining how the invention worked.

And BTW, the newest of the patents (10,019,458) issued just 5 years ago (7-10-2018). At the time, Alice v. CLS Bank had been in existence for 4 years. 4 years after Alice and the USPTO still cannot recognize patent eligible subject matter from patent ineligible subject matter? If the USPTO cannot, how can inventors, patent practitioners, investors, Federal Judges do the same?

And for the last BTW, if I was prosecuting the claims of the 10,019,458 patent, I would not be expecting a 101 rejection. Moreover, even if I did get a 101 rejection, it would be an easy argument under the 2019 Patent Eligibility guidelines to say that this was an improvement to computer technology and consequently patent eligible under 101.

If the USPTO really wanted to embarrass the Federal Circuit, they should put out a revised guidelines that points out all the inconsistencies in the Federal Circuit case law and essentially conclude “We have no guidelines to present. There is no way to satisfy the Federal Circuit case law without falling afoul of some other part.” Certainly, a pipe dream on my part, but someone (with authority) has to expose the Federal Circuit’s mangling of the law in such a clear and unmistakable manner that neither the Federal Circuit nor Congress can ignore it any longer.

This is an utterly infantile take on the situation that has been expressly rejected by the courts countless times.

You are trying to defend functional claiming at the point of novelty. You look more ridiculous in 2023 than you did in 2005.

Lastly, if there is some “inconsistency” in the case law, then the PTO can and should point it out, take a reasonable position on which version is best for the patent system (including a consideration of the public’s rights), and let the courts or the legislature decide if they made the right choice.

You really do not “get” the problem with the Gordian Knot, do you Malcolm?

¯\_(ツ)_/¯

WT: “ he problem is that when this extra stuff is put into the claims the Federal Circuit dismisses it as not being inventive”

The problem is that this “extra stuff” is ineligible subject matter in its own terms and simply reciting “do it on a computer” is not enough to fix the problem.

Claims that involve information processing/storage and logic are ALWAYS problematic from an eligibility standpoint and they ALWAYS will be. That’s because information processing and logic are ineligible subject matter.

Why is this so difficult to understand in 2023? Why do you pretend to be born yesterday? It didn’t work out too well for (spit) Sidney Powell.

This has exactly zero to do with anything from Sidney Powell.

Your “one-bucketing’ is egregious.

Terrible lawyers making stuff up to serve their personal interests at the expense of everyone else has everything to do with soon-to-be convicted trash pile Sidney Powell.

Your identification of the political has ZERO to do with the realm of patents.

You quite mistake being pro-patent as some type of “grifting for lawyers.

Let’s chalk this up to your known cognitive dissonance for creating personal property protection for innovators that does not fit with your heart’s anti-personal property Sprint Left beliefs.

Nothing is as perpetually amusing as your hilarious “keep politics out of my efforts to pass rotten laws that enrich my attorney friends at the expense of everybody else” blabbering.

The obvious correction, with the reading from Malcolm’s “position:”

“Nothing is as perpetually amusing as MY hilarious proving anon’s points.”

quoting legislative history for legislation that was NOT ADOPTED makes the opposite point that the Judge tried to make.

This is a very fair point. I admire Judge Newman’s dissent, but if it were my opinion to write, I would have styled it as a concurrence rather than a dissent (e.g., “while I agree that my colleagues reach the opinion that we are compelled to reach under applicable precedent, I write separately to emphasize how unworkable the applicable precedent is…” and then cite the various legislators who have expressed concerns). It is true, however, that—right up until Congress does promulgate a reformed statute—the failure of Congress to change the statute stands as a point in favor of the statutory stare decisis grounds on which the present jurisprudence rests. Bilski v. Kappos, 561 U.S. 593, 602 (2010).

You too quite miss the point that the current “stare decisis” is an UNWORKABLE Gordian Knot.

Howev”e”r…

Greg signaling with Drum quoting Matthew 6:5 is deliciously ironic.

Try to remember that Newman is playing with a 94 year old set of cards that is missing about half the deck.

You are clearly — and ever abundantly — wr0ng.

But you already know that, eh, Malcolm?

You absolutely misunderstand BOTH the point AND the context of the quotes.

Hint: new legislation — especially patent legislation — does not happen overnight and the quotes you misunderstand may merely be the seeds of future change — and definitely not making any type of opposite point for which the items were presented for.

OT, but this would be huge if it ever happened (which it won’t with Ds in power.)

link to youtube.com

Meh, this does not seem all that big a deal, as the counterpoint already stresses the existing situation that administrative agency guidance does not have the force of law.

Rules are interpreted in accordance with the guidance and the court now has to give Chevron deference to how the agency interprets the guidance. Listen to Hageman. She knows what she is talking about.

I beg to differ: see ANY of the well-published push-back against the Patent Office by the likes of Boundy.

court now has to give Chevron deference to how the agency interprets the guidance

Who really cares how the agency interprets guidance? Guidance is just that — guidance. It isn’t a rule. Guidance does not have the force of law.

Listen to Hageman. She knows what she is talking about.

She keeps talking about agencies attempting to enforce guidance. If the agencies are, then that is simply wrong. I’m made that argument many times before the patent office — that their guidance (i.e., the MPEP) does not have the force of law. Its stated in the MPEP itself.

Wandering, the issue is when the agency is enforcing rules whether the agency’s guidance of the rules can be interpreted de nova (which is what the bill says) or with Chevon deference.

Hageman does know what she is talking about. She has litigated many cases where she defends ranchers from federal agencies.

Anon doesn’t understand the APA and all its implications.

You could not be more wrong Night Writer, as it is you that clearly do not understand the APA.

Here – for example – you make the simple error of thinking that Chevron deference applies equally to every administrative agency.

It does not.

Wandering, the issue is when the agency is enforcing rules whether the agency’s guidance of the rules can be interpreted de nova (which is what the bill says) or with Chevon deference.

Guidance is just that — it is guidance — it isn’t the rules.

If an agency is given the power to promulgate rules to implement certain statutes, then Chevron guidance means that the federal courts will defer to the agency’s reasonable interpretation of an ambiguous statute. If the statute isn’t ambiguous, then there is no deference given.

Hageman does know what she is talking about. She has litigated many cases where she defends ranchers from federal agencies.

I’ve been defending my clients regarding the actions of a federal agency for well into my 3rd decade. What of it?

As I noted to Night Writer, the administrative agency related to ranchers and the administrative agency related to patents have very different charter rules (and powers) as administrative agencies.

He is making the mistake of thinking that administrative agencies (somehow) necessarily have identical powers and levels of power in being an administrative agency.

They do not.

Comments are closed.