“[N]othing in the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure or this Court’s decisions provide any basis for district courts to depart from the usual standards for summary judgment in cases involving review under the Administrative Procedures Act.” – Hyatt petition

Gilbert Hyatt

Gilbert Hyatt, an inventor who has been granted more than 70 patents and has filed more than 400 applications with the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO), has petitioned the U.S. Supreme Court asking the Justices to weigh in on his challenge of a policy he alleges the USPTO implemented in the 1990s to categorically deny him issuance of any additional patents. Hyatt has been embroiled in litigation with the USPTO for decades and won a previous Supreme Court appeal in 2012.

In his latest petition, Hyatt is asking the Court to answer the following two questions:

- Whether the ordinary summary judgment standard of Rule 56 applies to review of agency action, as held by the First, Fifth, Ninth, and District of Columbia Circuits.

2. Whether the mandamus standard of Norton v. S. Utah Wilderness Alliance, 542 U.S. 55 (2004), applies to claims seeking to set aside agency action under 5 U.S.C. § 706(2)

In the underlying case on appeal, Hyatt sought to compel agency action on his applications pursuant to the Administrative Procedure Act (APA), Section 706(1). Second, Hyatt brought an APA Section 706(2) claim to hold unlawful and set aside the USPTO’s so-called “no-patents-for Hyatt” rule. The district court found that Hyatt had plausibly alleged the existence of the USPTO’s rule barring him from getting patents, but “sua sponte entered summary judgment against him, notwithstanding clear disputes of material fact as to the agency’s actions…. [because] the ordinary summary judgment standard of Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 56 does not apply in agency cases.” Furthermore, the district court held that, “because there was no basis to ‘compel agency action unlawfully withheld or unreasonably delayed,’ 5 U.S.C. § 706(1), the agency’s rule could not be ‘h[e]ld unlawful and set aside’ as ‘arbitrary, capricious, an abuse of discretion, or otherwise not in accordance with law,’ id. § 706(2).” The Federal Circuit later upheld this decision via a Rule 36 judgment.

No Patents for Hyatt

Hyatt alleges in the petition that he has numerous patent applications pending before the Office that were filed “decades ago” with either no action or that have recently been held abandoned. The origin of this inaction has to do with a policy enacted by the USPTO in the mid-1990s to combat so-called submarine patents, which are “patents with early filing dates covering technology that was widely adopted by the time of issuance.” Former USPTO Director Bruce Lehman cracked down on such patents and the Office subsequently targeted Hyatt as a submariner—mistakenly, according to the petition. The petition references declarations made by several former USPTO employees attesting to the existence of the “no-patents-for-Hyatt rule” and claims that the agency simply took no action on his applications between 2003 and 2013.

Throughout the 2000s, the “rule” evolved further, becoming “even stricter,” and “from 2007 to 2012, the PTO issued approximately 2,200 suspensions of examination in Hyatt’s applications,” says the petition. Furthermore, the Office assigned 100 of Hyatt’s applications to a single examiner; delaying filing of its briefs in district court litigation; and reopening prosecution of applications that prevailed on administrative appeal; creating a special art unit, known as the “Hyatt Unit,” in 2012 and 2013 dedicated to prejudicially handling Hyatt’s applications; among other tactics.

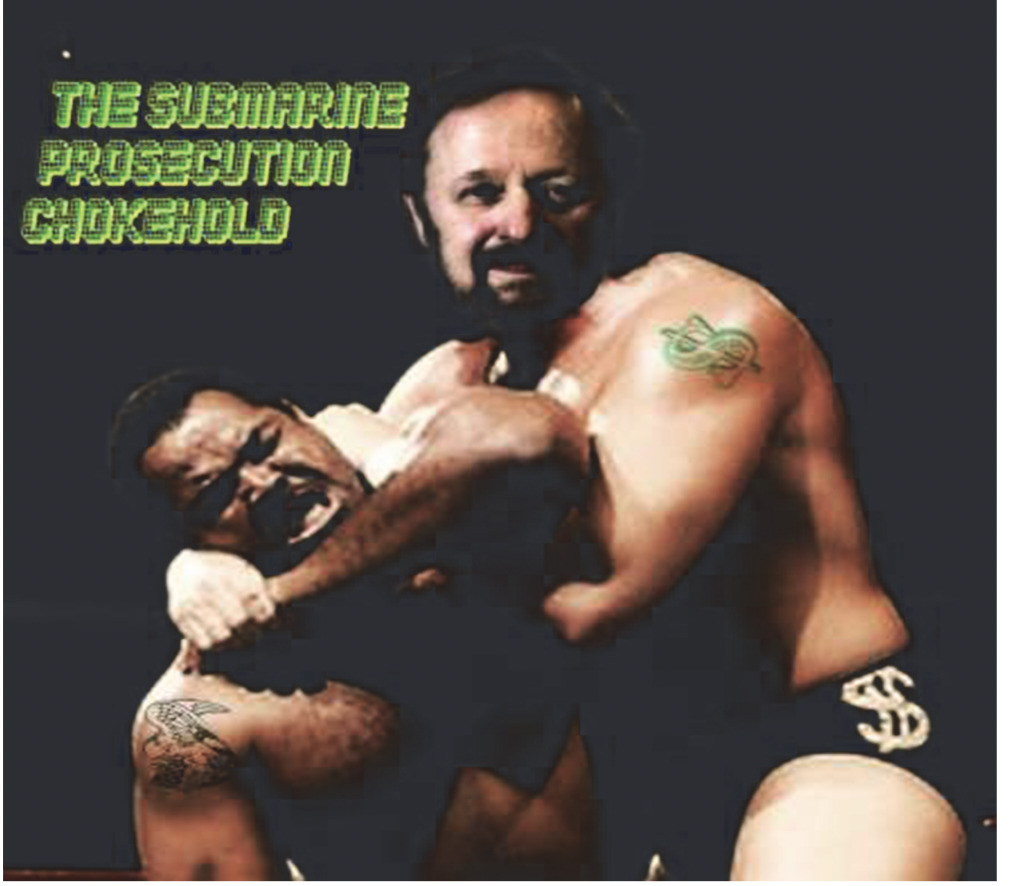

The petition also notes a number of emails obtained via FOIA requests that demonstrate bad faith, including an image circulated among examiners of Hyatt’s face superimposed on a wrestler choking his opponent, who bears the USPTO seal. The image was apparently labeled “THE SUBMARINE PROSECUTION CHOKEHOLD.”

Reasons to Review

Ultimately, Hyatt argues that the district court’s deviation from the usual Rule 56 summary judgment standard is “crucial” and must be corrected, since a split among circuits now also exists:

[N]othing in the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure or this Court’s decisions provide any basis for district courts to depart from the usual standards for summary judgment in cases involving review under the Administrative Procedures Act. Decisions from the First, Eleventh, Fifth, Ninth, and D.C. Circuits directly conflict with the district cou rt’s ruling, and therefore the Federal Circuit’s decision in this case.

Finally, the district court’s rejection of Hyatt’s Section 706 claims arose due to its erroneous importation of Section 706(1) requirements into Section 706(2). The petition explains:

Under the district court’s approach, the government can forever deny Hyatt any patents. For example, the patent examiner can delay jurisdiction passing to the Patent and Trademark Appeals Board (“PTAB”) by taking a long time to file office actions and reopening examinations after filing those actions. See 37 C.F.R. §§ 1.104, 1.111(a), 41.35. Even after the PTAB’s jurisdiction vests, an examiner can head off a final patentability determination (which in turn heads off judicial review) by delaying filing their examiners’ answer. See 37 C.F.R. 41.39(a) (establishing that there is no statutory deadline for an examiner to file their answer with the PTAB). All of this is to say that the USPTO can take some action on Hyatt’s applications while still maintaining a rule to deny him patents and judicial review. Yet, the district court held that the “PTO’s actions on plaintiff ’s patent applications are the reason this suit must end.” S.App. at 33. This conclusion may be sufficient to deny mandamus under Rule § 706(1), but it should not be sufficient to deny relief § 706(2) on the ground that the agency action is arbitrary or capricious.

![[IPWatchdog Logo]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/themes/IPWatchdog%20-%202023/assets/images/temp/logo-small@2x.png)

![[[Advertisement]]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/Patent-Litigation-Masters-2024-banner-early-bird-ends-Apr-21-last-chance-938x313-1.jpeg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/Patent-Litigation-Masters-2024-sidebar-early-bird-ends-Apr-21-last-chance-700x500-1.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/WEBINAR-336-x-280-px.png)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/2021-Patent-Practice-on-Demand-recorded-Feb-2021-336-x-280.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/Ad-4-The-Invent-Patent-System™.png)

Join the Discussion

No comments yet.