It's always good to have a villain, a "Snidely Whiplash" or other cartoon caricature to support an argument, especially if the issue is complex and fails the cocktail party test.* The New York Times is (in)famous for these types of intellectually lazy arguments when it comes to patents (see "Top Stories of 2022: #8 to #10"; #9. New York Times Reopens Attack on U.S. Patent System), and they were at it again on Sunday in a front page piece on Humira, a drug used for a variety of ailments that has brought relief to millions of patients who otherwise suffered with earlier, less effective drugs. (At least in the past the Times has had the good sense to relegate such articles to the Op-Ed pages.)

The problem seems to be that Humira has made a pharma company a lot of money (purportedly $116 billion), that the drug is expensive (said to cost upwards of $50,000/year) and that the drug company has amassed a large number of patents to protect its intellectual property. The bigger problem is that the article fails to recognize several important facts relating to the circumstances under which Humira's makers made this money and amassed its patent estate (or "thicket" as the anti-patent crowd likes to call it).

The first of these is that until 2010 there was no pathway for "genetic" (accurately, "biosimilar") competition for innovator biologic drugs (the class of drugs including Humira). This has nothing to do with patents; the FDA could not approve a biosimilar competitor by law until the Biologic Price Competition and Innovation Act (BPCIA) was passed as part of Obamacare (see "Follow-on Biologics News Briefs - No. 11"; "House Passes Health Care Reform Bill -- Biosimilar Regulatory Pathway Makes Cut, Pay-for-Delay Ban Does Not"). Thereafter, the FDA needed to develop guidelines (see "FDA Looks to Multiple Sources, Including EMA Guidelines, in Developing Biosimilar Approval Standards") and Guidances (see "FDA Publishes Draft Guidelines for Biosimilar Product Development"; "FDA Releases "Final" Guidances for Industry regarding the Biosimilar Approval Pathway") establishing the standards under which biosimilar drugs could be approved; while still on-going for certain types of biosimilars these efforts took about 5 years to be promulgated (the FDA engaging with stakeholders to ensure the efforts were fair and robust enough to minimize the possibility of approving drugs that were not "similar enough" to avoid safety, potency, or efficacy issues).

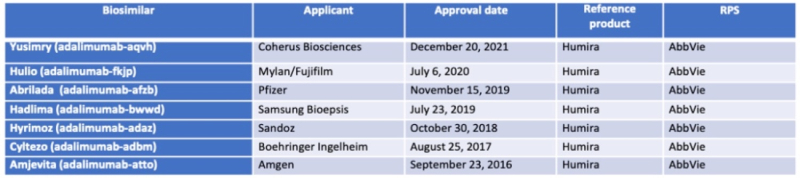

The first approved biosimilar was Zarxio from Sandoz, which competes with Amgen's Neupogen, an adjuvant for cancer patients for treating side effects of chemotherapy (see "FDA Approves Sandoz Filgrastim Biosimilar"). Humira biosimilars have been pursued by several companies and FDA has approved seven (see, e.g., "FDA Approves Amjevita -- Amgen's HUMIRA® Biosimilar") and this table:

(With one of them, Cyltezo, being designated as an interchangeable biosimilar, see "FDA Approves Another Interchangeable Biosimilar Drug", which is highly sought after because it has advantages, see "FDA Issues Final Guidance Regarding Biosimilar Interchangeability", similar to what can be achieved for a small molecule drug.)

Immediately it will be clear that a great deal of the $116 billion cited to raise the temperature of the debate (and the purported perfidy of Humira's producer) was made during the time that it was impossible to compete, and that once a pathway had been opened several companies took the steps to do so. But although there was this large patent estate accumulated when litigation ensued, the number of patents asserted and claimed was but a minuscule portion of the estate. As for types of patents accumulated, much is made in the article about the patent on the active pharmaceutical product (the drug) expired in 2016, as if that was the only patent upon which Humira was entitled to rely. The first source of error in this assertion is that most of the current biologic drugs were approved so long ago that they similarly no longer have patent protection on the drug molecule itself. But due to the complexity of producing these drugs commercially, they all have protection on those methods (without which the drugs could not be produced and regarding which each sponsor company invested money, time, and effort to develop). Humira is not alone nor an outlier on such protection and these patents protecting how the drugs are made are no less worthy than the drug patent itself.

The irony of ironies in this story printed this Sunday is that this Tuesday, January 31st, those eight Humira biosimilar-approved companies will be able to sell their biosimilar Humira free of all the patents in the patent estate, pursuant to a settlement agreement (see, e.g., "HUMIRA® Biosimilar Update -- Settlement in AbbVie v. Amgen Case Announced and AbbVie v. Boehringer Ingelheim Litigation Begins"; "AbbVie Announces Global Resolution of HUMIRA® (adalimumab) Patent Disputes with Sandoz"), with others as yet not approved being licensed to go on the market on July 1st and September 30th of this year. As mentioned above, the overwhelming number of the Humira patents were not asserted but could have been asserted to prevent these Humira biosimilars from being marketed for many more years. Inconsistent with the bad guy caricature promulgated by the Times, the cases were settled, benefiting the public at the real-world expense of Humira's drug maker.

Two other points bear mentioning. First, the 7th Circuit Court of Appeals decided last year that the Humira patent estate was not an antitrust violation and thus fear of antitrust liability is not a factor in these settlements (see "Mayor and City Council of Baltimore v. AbbVie Inc. (7th Cir. 2022)"). The second point is that the FTC in a 2009 white paper (see "No One Seems Happy with Follow-on Biologics According to the FTC") predicted that the price reduction benefit of biosimilar would be about 30%, that is that the cost of a biosimilar equivalent to a patented biologic drug would be about 70% of the reference biologic drug price. With admittedly few data points, that prediction has been borne out so far, meaning that instead of $116 billion the cost for an equivalent period of time an amount of Humira biosimilar sales can be expected to be $82 billion. As Sen. Dirksen would say that is real money but hardly the type of windfall public benefit that small molecule drug genetics represent (which sell for about 10% of the innovator price).

The real issue is that the development cost of biologic drugs is much higher than traditional small molecule drugs as is the cost of producing them. Everyone thinks "drugs cost too much" and want them to be cheaper but the reality (in a capitalist society) is that there needs to be sufficient prospect of return on investment to justify development. The entire economic argument is TLDR (which is why articles like the one in Sunday's Times is both easy and incomplete); for a good and accurate explication of the patent side of this issue, Professor Adam Mossoff at George Mason University has published a report for the Hudson Institute (see "Unreliable Data Have Infected the Policy Debates Over Drug Patents"), which, while generating less heat than the Times article, does shed enormously more light (see "Faux-Populist Patent Fantasies from The New York Times"). Suffice it to say that while it may make the medically self-righteous feel better, it does little to advance the real debate about how to ensure that people who need drugs (and medical care generally) can get them. That's too complicated for a lazy winter Sunday afternoon reading the Times, but the issue deserves more than this shallow level of analysis and rhetoric.

* Where you are likely to be talking to yourself in under five minutes if you bring up the subject.