The efforts to have Judge Pauline Newman, Circuit Judge on the Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit, unfit or guilty of misconduct have been the subject of reporting in the patent blogosphere (Patently-O, IP Watchdog), the general legal press (Bloomberg Law, IPLaw360) and the popular press (Reuters) for over a month. The dispute rose in intensity earlier this month, when Judge Newman filed on her behalf a complaint in the District Court for the District of Columbia. The caption named Judge Newman as plaintiff and Chief Judge Kimberly Moore, Judge Sharon Prost, and Judge Richard Taranto, members of the Special Committee of the Judicial Council of the Federal Circuit, as defendants.

Judge Newman's complaint sets out some factual bona fides, such as that she was the first judge specifically appointed to the Federal Circuit (by President Reagan) in 1984 and (she asserts) has "continued to faithfully, diligently, and meticulously exercise the duties of her office, to recognition and acclaim," including being named as "one of the 50 most influential people in the IP world" by Managing IP Magazine in 2018. She contends that she has "has been and is in sound physical and mental health" at all relevant times and asserts that she has performed her duties (including that she has "authored majority and dissenting opinions in the whole range of cases before her Court, has voted on petitions for rehearing en banc, and has joined in the en banc decisions of the Court"). The complaint identifies four opinions Judge Newman has filed between March 6th and April 6th, and had also participated in an en banc proceeding during this time (with no objection from her brethren).

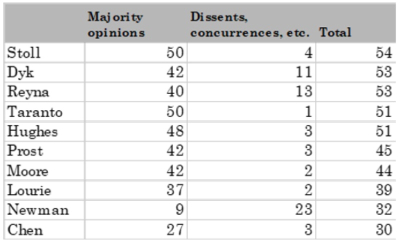

These assertions are backed up by a Guest Post in Patently-O by Temple Professor Paul R. Gugliuzza showing the Federal Circuit Judges' activities over the term from June 1, 2021 through December 31, 2022:

Judge Newman cites Professor Gugliuzza's report in her complaint, asserting that this report "stand[s] in sharp contrast to the[] false allegations" raised against her.

It will be noted that while Judge Newman has penned far fewer majority opinions during this time than her colleagues, she has also penned many more dissents, so that her total opinion output (while less than most other judges on the court) is in the range of the lower one quarter of them. This outcome should not be surprising; for many reasons Judge Newman and her colleagues do not see eye-to-eye on a sufficient percentage of the patent law questions that come before the court that the Judge has been dubbed "The Great Dissenter" in patent circles (see Lim, I Dissent: The Federal Circuit's "Great Dissenter," Her Influence on the Patent Dialogue, and Why It Matters, 19 Vanderbilt Journal of Entertainment and Technology Law 873 (2020)). In this regard, the complaint notes that "[o]ften, Judge Newman's dissenting opinions are adopted by the Supreme Court in its frequent reversals of the Federal Circuit."

Enumerated in the complaint is a history of seven Orders handed down in this dispute by the Special Committee to date, the first of which issued on March 24th. That Order asserted that Judge Newman's colleagues had noticed deficiencies in her performance of sufficient gravity that an inquiry by the Special Committee was necessary.*

Judge Newman in her complaint characterizes the March 24th Order as being "riddled with errors," including that the Judge was incapacitated due to a heart attack and subsequent coronary stent surgery at a time when Judge Newman asserts she "sat on ten panels and issued at least eight (including majority, concurring, and dissenting) opinions." Judge Newman's participation on ten panels during that time was more than only two other Federal Circuit judges, the complaint contends.

Judge Newman asserts that the Chief Judge "unconstitutionally and unilaterally removed [her] from all future sittings of the Court," purportedly with the unanimous consent of her judicial colleagues. In fact Judge Newman has not been permitted to sit on any panels since the March 24th Order, despite requesting to do so.

The March 24th Order has been superseded by an April 6th Order which "expanded the scope" of the investigation to include "questions of internal operations of Judge Newman's chambers," and a day later there was another Order "demanding that Judge Newman submit to neurological and neuropsychological examinations before physicians of the special committee's choosing." Judge Newman asserts she was given three days to comply (emphasis in complaint).

Failure to comply was the basis, the complaint asserts, for yet another Order on April 13th "further expanding the scope of investigation" into "additional misconduct."

This was followed by an April 17th Order "demanding that Judge Newman share private medical records regarding medical events identified in the March 24th Order," this time providing four days to comply (emphasis in complaint).

The complaint further asserts that the Chief Judge "unilaterally reassigned one of Judge Newman's law clerks to the chambers of another Judge" and has refused to "authorize a search for a new judicial assistant." Similarly, the complaint asserts the Chief Judge unilaterally reassigned one of Judge Newman's law clerks (the return of this individual apparently not being an option due to "the strained relationship that developed between Judge Newman and this law clerk"). Again, the complaint asserts the Chief Judge has not authorized Judge Newman to replace this law clerk, despite (as a currently active judge on the court) she is "statutorily entitled to four law clerks and a judicial assistant."

Another Order on April 21st alleged it to be misconduct for Judge Newman not to assign her law clerk to another judge's chambers.

Judge Newman, through counsel, sent the Chief Judge a letter on April 21st requesting restoration of her hearing calendar and for the Judicial Complaint to be transferred to a different Judicial Council pursuant to Rule 26 of the Conduct Rules. In the letter Judge Newman raised due process concerns, stating that "basic norms of due process cannot permit the same individuals to be accusers, witnesses, rapporteurs, and adjudicators of a complaint against her," her position being supported by "opinions of leading judicial ethics experts who have unequivocally stated that in these circumstances transfer to another circuit's judicial council is necessary."

A May 3rd Order (which Judge Newman characterizes as a "gag order") prohibits the Judge from publicizing the investigation by herself or her counsel and to be subject to sanctions, even if such disclosure were made pursuant to Rule 23(b)(7) of the judicial Conduct Rules.

Another May 3rd Order denied Judge Newman's request to transfer the investigation to another Judicial Council, and contained another Order that Judge Newman "submit to neurological and neuropsychological examinations before physicians of the special committee's choosing" and "surrender medical records including for events that have never occurred." This time the Order gave Judge Newman a week to comply.

Judge Newman asserts that she does not object to undergoing a medical examination but she does object to "not being able to select or even participate in the selection of a medical professional to examine her, and to having no input into the scope of the medical investigation."

Significantly, the complaint at Paragraph 38 states that "If and when the special committee proceeds to a hearing as contemplated by Rules 14(b) and 15(c), Judge Newman intends to call, and compel witness testimony from each member of the Judicial Council as is her right under the aforementioned rules."

In her Prayer for Relief, Judge Newman alleges in Claim I "improper removal [and] violation of separation of powers" based on Article III (life tenure of federal judges) and Article I (giving the House of Representatives the sole authority to remove a judge through impeachment after trial by the Senate). Judge Newman characterizes the several Orders as being unlawful for removing her from hearing cases, removing her judicial staff without her consent, ordering her to "undergo an involuntary mental health examination without a sufficient basis or legal authority for doing so, by physicians unknown to and unapproved by Plaintiff," and ordering the scope of the investigation to be expanded "merely because Plaintiff requires time to properly evaluate and answer special committee requests."

Claim II asserts that the Judicial Complaint is ultra vires for "improper removal [and] violation of separation of powers." This allegation is based on Judge Newman being removed from her duties before the special committee's investigation was concluded (which removal the Judicial Disability Act of 1980 codified at 28 U.S.C. § 354(a)(2)(A)(i) requires to be after the investigation according to the complaint). "'Sentence first—verdict afterwards' is a notorious and textbook example of deprivation of due process known even to children's literature" the complaint asserts. This Claim alleges irreparable harm until the Orders "excluding Plaintiff from regular duties of an Article III judge and their threats to continue with such exclusion" and "requiring Plaintiff to refrain from publicizing the proceedings against her and publicly defending herself from the outrageous complaint lodged against her" are enjoined.

Claim III alleges Fifth Amendment violations of due process because the members of the Special Committee are also purported witnesses to the alleged judicial misconduct (the complaint stating that "[i]t has been established for centuries that one cannot serve as a 'judge in his own cause'").

Claim IV asserts a First Amendment violation for unlawful prior restraint for the gag order, contrary to Houston Cmty. Coll. Sys. v. Wilson, 142 S. Ct. 1253, 1259 (2022) (the First Amendment prohibits prior restraint on speech); Alexander v. United States, 509 U.S. 544, 550 (1993) (gag orders are a form of prior restraint); Bantam Books, Inc. v. Sullivan, 372 U.S. 58, 70 (1963) (there is a heavy presumption against gag orders); Reed v. Town of Gilbert, Ariz., 576 U.S. 155, 163 (2015) (gag orders are subject to strict scrutiny).

Claim V asserts that the gag order is also ultra vires as being an unlawful prior restraint on speech.

Claim VI asserts a Fifth Amendment violation for unconstitutional vagueness of the provisions of the Disability Act. Judge Newman asserts that she has "liberty and property interests in the outcome of any misconduct or disability proceeding against her" and "liberty and property interests in not being subjected to an involuntary medical or psychiatric examination and further liberty and property interests in not being stigmatized as having committed misconduct and having her mental health questioned, as well as having her status as an Article III judge altered by ordering her to undergo a compelled medical or psychiatric evaluation by physicians not chosen by her and who are unknown to her." And those interests also extend to her private medical records wherein they "may not be invaded by requiring her to surrender these same records to an investigative authority absent due process of law." These assertions are directed at the Act as well as how the provisions of the Act have been implemented in this instance.

Claim VII asserts that the activities are ultra vires for unconstitutional examination because "[n]either the Act nor the U.S. Constitution authorizes compelling an Article III judge to undergo a medical or psychiatric examination or to surrender to any investigative authority her private medical records in furtherance of an investigation into whether the judge suffers from a mental or physical disability that renders her unable to discharge all the duties of office." Judge Newman asserts that "Defendants have neither statutory nor constitutional power to compel Plaintiff to undergo an involuntary medical or psychiatric examination, or to compel Plaintiff to surrender her private medical records."

Claim VIII is also asserts a Fifth Amendment violation for unconstitutional vagueness regarding the Act's investigative authority, with regard to "authoriz[ing] compelled medical or psychiatric examinations of Article III judges or demands from special committees for Article III judges to surrender their private medical records." In particular, this allegation is directed to Section 353(c) of the Act.

Claim IX alleges a Fourth Amendment violation for an unconstitutional search regarding the "compelled medical or psychiatric examination of an Article III judge without a warrant based on probable cause and issued by a neutral judicial official or a demonstration of constitutional reasonableness."

Claim X alleges a Fourth Amendment violation for an unconstitutional search and seizure of a "compelled surrender of private medical records."

Claim XI alleges a Fourth Amendment violation for "lack[ing] either a warrant issued on probable cause by a neutral judicial official or a constitutionally reasonable basis for requiring Plaintiff to submit to an involuntary medical or psychiatric examination."

Claim XII alleges a Fourth Amendment violation for "lack[ing] either a warrant issued on probable cause by a neutral judicial official or a constitutionally reasonable basis for requiring Plaintiff to surrender her private medical records none of which bear on her fitness to continue serving as an Article III judge."

The Relief Requested is:

(1) declare the Act to be unconstitutional, either in whole or in part and enjoin Defendants from enforcing the Act to the extent it is unconstitutional;

(2) declare any continued proceedings against Plaintiff by the Judicial Council of the Federal Circuit to be unconstitutional as violative of due process of law and enjoin Defendants from continuing any such proceedings, except to the extent necessary to transfer the matter to a judicial council of another circuit;

(3) order the termination of any further investigation of Plaintiff by the Judicial Council of the Federal Circuit;

(4) declare any decisions by any and all Defendants authorizing a limitation of Plaintiff's docket or other special restrictions on her actions as a federal judge, including, but not limited to the reduction in statutorily authorized number of staff to be unconstitutional and/or not in accordance with the law, and enjoin Defendants from continuing any such actions;

(5) declare any orders precluding Plaintiff from publicizing or otherwise speaking about the ongoing disciplinary proceedings to be unconstitutional and/or not in accordance with the law and enjoin Defendants from enforcing the foregoing unconstitutional orders;

(6) declare any orders of the special committee requiring Plaintiff to undergo a compelled medical or psychiatric examination and/or disciplining Plaintiff for objecting in good faith to these demands to be unconstitutional and enjoin Defendants from enforcing the foregoing unconstitutional orders;

(7) declare any orders of the special committee requiring Plaintiff to surrender her private medical records and/or disciplining Plaintiff for objecting in good faith to these demands to be unconstitutional and enjoin Defendants from enforcing the foregoing unconstitutional orders;

(8) award Plaintiff reasonable attorneys' fees and costs; and

(9) grant Plaintiff such other relief as the Court deems just and proper.

It may be significant to note that Judge Newman has been an active Federal Circuit judge longer than any other member of the Court.

* Judge Newman also asserts that Chief Judge Moore has tried in the past to "coax" her into retirement, and that the Chief Judge used the existence of a complaint against the Judge in an attempt to further coax (or coerce) the Judge to retire.